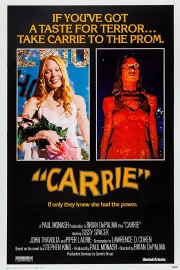

Carrie

How on Earth did Brian De Palma get away with showing so much nudity in the locker room scene that opens his 1976 thriller, “Carrie?” I mean, I get that the ’70s were a heady time, the sexual revolution, and all that, but man, the way he shoots the scene is completely voyeuristic and more in keeping with a soft-core film than the serious, Oscar-nominated film it ended up being. Yes, I know that’s a bizarre way to start a review to a genuine horror masterpiece, but needless to say, it’s been a while since I’ve seen the film, and so it was a bit of a shock to watch that opening.

De Palma doesn’t glorify or make a mockery of the tragedy of Stephen King’s indelible character, Carrie White, though. The horror begins early, and subtly, when is showering, and has her first period. She freaks out (Carrie’s mother never told her about this), but the other girls, now dressed, make fun of her, throwing tampons at her and cornering her in the shower. Her teacher reacts roughly, as well, but only because she doesn’t know what else to do. However, when Carrie gets stressed, something happens, and one of the lights in the shower goes out. Similar things occur when she is called into the principal’s office, and when she’s home, and her hyper-religious mother (Piper Laurie) locks her in a closet. It turns out that Carrie has telekinetic abilities, and while it scares her, it also helps her in unexpected ways when the bullying gets worse as the prom gets closer, even when she gets an unlikely invitation.

What makes “Carrie” into a great horror film, however, isn’t the high school bullying that frames the story, but the horrors at home. Carrie and her mother have a relationship that is, at once, simple but complicated. Her mother is a God-fearing woman, aware of the sins the world has available, but so delusional in her thinking that she’s completely sheltered Carrie, turning her into a socially-inept young woman. Her mother might be perceptive, though, because she knows that going to the prom with the popular jock who asked her out of the blue could be humiliating for her daughter. Not for the reasons mother thinks, though. Carrie goes anyway, looking forward to one night of happiness in her young life, but what happens leads to one of the most unforgettable moments in movie history.

For someone who wasn’t in the “in crowd” in high school, the pain in King’s story, and in Lawrence D. Cohen’s screenplay, is very potent. Even more potent, however, is the realization that bullying like the kind that Carrie White endures here is still occurring in the real world, and that’s a sad thought. Of course, people who endure such torture in high school now don’t have the “gifts” Carrie does to combat it, but it’d be adding tragedy upon tragedy if such things were real. Instead, the bullied in real life look inward, internalizing what they’re told by others until they believe it themselves, leading to tragic results in their own right. (Ironically, perhaps, it’s because of religious fundamentalist beliefs along the lines of Carrie’s mother that a lot of bullying of others takes place now, rather than the other way around, like it is here.) That De Palma gets to the core reality of this tale, and the heartbreaking emotional toll it takes, makes the film even harder to watch, especially when Carrie’s fate is sealed at the prom.

The final 20 minutes or so of this film is De Palma at his finest. Best known for his sometimes all-too-blatant Hitchcock homage in most of his films, the director of such iconic films such as “The Untouchables” and “Scarface” utilizes such Hitch tics in “Carrie,” especially a shrieking string section that is right out of “Psycho,” but relies more on the powerful imagery King’s story suggested to turn the film into a horror classic for the ages. It helps, though, that he has two women at the heart of the film that understand these characters inside out. As Carrie, I don’t know if Sissy Spacek’s performance could possibly be topped, even by someone as gifted as Chloe Moretz, who stars in the recent remake. Spacek conveys a weakness that makes the character so accessible, and palpable, that it’s stunning to see the strength Carrie has to muster to not only go to the prom, but do what she does to survive when she gets home, and her mother (played by Laurie in an equally unforgettable turn) tries to cast out what she sees as a demon child. Instead, she does so herself in one of the most unsettling twists of any King story. Of course, I should also mention Amy Irving as one of the cool kids at Bates High School. It’s her boyfriend that asked Carrie to the prom. She’s the only one left after what happened at on prom night, and we see that, what seemed to be a setup for a cruel joke on her part was, in fact, a genuine show of concern for this lonely girl. In the end, though, that doesn’t mean much to Carrie, who is ready to drag her down as well in a classic final image of a hand coming out of the ground. De Palma doesn’t shy away from the terror of King’s story, and neither should we, when we consider what it says about the life of a teenager in pain.