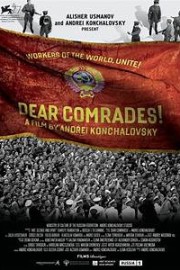

Dear Comrades

Given the events in “Dear Comrades,” we are left wondering both how the Soviet Union remained a communist regime through to the end of the 1980s, and are not surprised at all. Between this and HBO’s “Chernobyl” last year, we see about as authentic a look at the machinations of the way the Soviet Union did business during the Cold War, and it’s fascinating. Here, we get a look at one of the most significant examples at the brutality of the Soviet Union against its people, and honestly, I wouldn’t be surprised if you see some comparisons to modern America, and the Black Lives Matters protests that have happened almost every year since 2014.

This historical drama is a retelling of the Novocherkassk massacre in June 1962. Workers at an Electromotive Building Factory had organized a labor strike several weeks before, one that was inspired by an increase in production quotas, along with a nationwide increase in dairy and meat prices. The combination led to mass protests that were then extinguished by armed forces who shot into the crowd; up to that point, the government had a policy of not firing on its own people, and by the end of the protest, 26 protesters were killed, and another 87 were wounded. It would not be for another 30 years, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when official inquiries would take place, by which point several of those held responsible were dead.

One of the things that makes “Dear Comrades” so intriguing is that it is seen from the perspective of Lyudmila “Lyuda” Syomina (Julia Vysotskaya), a party worker of the local city committee, and a staunch communist. She is witness to the shooting, and to the order of silence the government takes on the matter. During the protest, Lyuda’s daughter disappears; she was in the protests, and her disappearance causes a change in perspective in Lyuda, calling into question everything she believed in the party she served as she tries to find her daughter. Normally, a filmmaker would look at an event like this from a variety angles and perspectives, but by focusing on the government side of things, and not the front lines of the protests themselves, co-writer/director Andrey Konchalovskiy allows us not to experience things solely from Lyuda’s point-of-view and her change, but also see the inner workings of the communist bureaucracy itself, and their collective disregard for their citizens on the whole. He doesn’t quite delve into dark comedy, but his disdain for the Soviet communist government is as palpable here as it was in his collaborations with Andrei Tarkovsky as a writer. His alignment is fully with the people on the outside, the people who wouldn’t see their loved ones, and those who would not know the truth behind why for another 30 years. By the end, we have taken a profound emotional journey, through the eyes of a woman who saw the world one way as the film began, and another way entirely by the end. It is an enlightening experience.