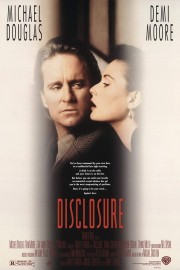

Disclosure

The hilarious thing about Michael Crichton’s writing is that his sci-fi adventures have dated better than his corporate thrillers. Stuff such as Congo and Jurassic Park and “Westworld” may be silly, but the way the worlds are built get to fundamental truths about society and human nature in a way that seeps underneath the spectacle. Rewatching “Rising Sun” a couple of years ago, and “Disclosure” now, he’s certainly saying things about the shady ways corporations do business, but in a way that wants to reflect reality. The results have always been controversial, rightfully so, but also haven’t aged well. Both films are ridiculous pulp thrillers, and both are entertaining for a lot of reasons, but in the long run, Crichton had more a knack for using fantasy to illuminate reality than trying to show reality.

Barry Levinson’s adaptation of “Disclosure” was the first film my friend Ron and I saw in theatres. We had been in Spanish together that semester in high school, and we decided to watch something after early release together. Given the trajectory of our film appreciation after we started hanging out again in the 2000s, this is such a weird choice, but neither of us had seen it. That’s the most noteworthy thing about my history with “Disclosure”- I can’t say I remember the discussion we had after the fact. I wish I had, if only because it might have been a good way to look at how I discussed some topics then vs. how I feel about them now.

In the age of #MeToo, “Disclosure’s” sexual politics are even more horribly misguided than they were in 1994. Certainly, women in power can sexually harass men just as easily as men in power can harass women, but the way “Disclosure” does things, even Meredith Johnson (Demi Moore), the corporate ladder climber whom harasses former lover Tom Sanders (Michael Douglas), now a family man, the week of a corporate merger seems like she’s just a pawn of the company’s CEO, Bob Garvin (Donald Sutherland), to get what he wants. We now know that harassers are often shielded by a system that condones such behavior, and sometimes rewards it, and that seems to be one of Crichton’s points, but having Meredith be a 1-dimensional manipulator who seems to use her sexuality to get her way rather than an actual character makes her as cartoonish a villain as a Crichton story has ever had. (The film also plays to the male fear of false allegations of harassment, and decides, “How can we make this even more frightening? She harasses HIM!”) She’s basically intended as bait for yet another Douglas character to get into trouble by following his dick. There is something to be said about the way Levinson and screenwriter Paul Attanasio genuinely make Tom a victim- and someone too trusting to a fault- but it would have been nice to see some real layers to Meredith as a character, as well. Why does she feel entitled to harass him? Why does she feel she needs to- is Garvin threatening her job, as well? Answers to those questions might have given “Disclosure” some lasting strength as a conversation starter.

Even if Levinson’s film feels like a film married to a specific time in how it approaches the conversation of sexual harassment and corporate politics, it remains a fun, wild ride. There is a great cast of supporting characters surrounding Douglas and Moore, from the lecherous (like Sutherland and Dylan Baker) to the sympathetic (like Caroline Goodall as Tom’s wife and Roma Maffia as the attorney he seeks out after Meredith accuses him of harassment). Tom’s coworkers represent different perspectives, as well- Dennis Miller’s Mark is a smartass with a vulgar streak and Nicholas Sadler’s Don is a tech geek in the ’90s, while Rosemary Forsyth’s Stephanie is a smart businesswoman who seems like a good alternative to Meredith, Jacqueline Kim’s Cindy is Tom’s assistant, whom is supportive but also feels uncomfortable, and Suzie Plakson’s Hunter is a woman who chose to work in tech, and doesn’t feel like she gets her due for how much she’s worked her tail off. This is one of those studio thrillers from the 1990s that makes you really lament how much a good, deep ensemble of characters is undervalued by the system now. It takes a skilled team to make a movie, not just the stars and director. Studios used to understand that. So did filmmakers.

“Disclosure” may not stand up to scrutiny, but Levinson understood the assignment with Crichton’s narrative- the flaws in its sexual politics are inherent to the initial text- and though I wish he could have strengthened it for the screen, he gets how goofy this is, especially when Sanders enters his company’s outrageous virtual reality database at the end, a scene so ridiculous “Community” lampooned it beautifully in its sixth season. With a score by Ennio Morricone that is doing an awful lot of heavy lifting, “Disclosure” is still fun, so long as you take nothing it’s doing seriously as commentary on the world.