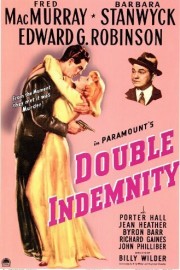

Double Indemnity

It doesn’t take long in “Double Indemnity” for the film, written by Billy Wilder and author Raymond Chandler (based on the novel by James M. Cain), to display a real example of what we consider “classic Hollywood cinema.” The scene takes place when we first see Fred MacMurray’s Walter Neff meet Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson, the woman who will lead this insurance salesman into a web of murder, fraud, and inevitable betrayal. This is a perfect example of the type of sharp-witted dialogue and banter that was prevalent in the ’40s as the genre we know now as film noir was being established. In this scene, Neff and Phyllis are dancing around an immediate attraction, flirting with one another, especially during the exchange where Neff and Phyllis are playing that Walter is a speeding motorist, and Phyllis is a police officer who pulls him over. What they’re really discussing is Phyllis slowing down Walter’s advances, which are understandable since when they meet, Phyllis has just gotten out of the shower. He’s immediately attracted to her, as his voiceover as she’s getting ready upstairs, makes clear. In this scene, the cinematography, editing, and music is less important than the dialogue by Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler, and the chemistry between the actors, both of which match up effortlessly to create an immediately memorable scene that will set in motion the entire story to come.

This type of suggestive, playful dialogue occurs throughout the film, in pretty much every scene between MacMurray and Stanwyck, and is indicative of the times in Hollywood and low-budget films. In the ’40s, with the release of John Huston’s “The Maltese Falcon,” a different attitude began to come out in crime films out of the studio system. The potboiler novels of Dashiell Hammett (the author of Falcon) and Chandler (author of The Big Sleep) began to find their way onto the big screen, and fundamentally changed the criminal world we saw onscreen. Gangsters and career criminals were less of a focus in these films than ordinary people who found themselves in criminal situations, sometimes of their own making, as is the case in “Double Indemnity.” Although the studio system was very much in full swing in 1944, when “Indemnity” was released, the film is less a product of a particular studio’s style and more a product of the genre, but that doesn’t make it any less a piece of classic Hollywood cinema.

Billy Wilder was a great filmmaker because of the ways he pulled and pushed film genres into interesting directions, even when he seemed to be playing right into the conventions of the genre. With “Double Indemnity,” Wilder does this by subverting the character’s, and the audience’s, expectations of what’s going to happen. After Walter and Phyllis murder Phyllis’s husband, after setting it up to make it look like an accident as a way of collecting the insurance on him, the big concern for the couple is a claims adjuster named Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), who has a “little man” (what we would now call a “sixth sense”) that acts up when something doesn’t add up about a claim. But in the first scene at the insurance office after the murder, Phyllis is called in by Walter and Keyes’s boss to see what she knows, and it seems as though the boss is the biggest threat to their plan, with Keyes inadvertently aiding their case. Later, though, the couple plans an illicit rendezvous at Walter’s apartment, but Keyes shows up first, and tells Neff that his “little man” is feeling something. It’s just too neat for him. After the release of feeling some freedom after the initial meeting, they are back on the defensive, concerned about whether their plan will work. This is the classic Hollywood ethos at it’s core– even when it seems to throw the audience for a loop, it doesn’t move far from a conventional narrative the viewer is familiar with, and the way it will play out.

It’s not simply the film’s embrace of “classic Hollywood” conventions, and Wilder’s subversion of them, that makes a film like “Double Indemnity” great, though. There’s a seductive nature to the film that can only come from the story and the characters. The pull that Neff and Phyllis feel towards one another, created from the effortless chemistry of the actors, is something that only great movies can unlock. Not just between Neff and Phyllis, though; arguably the most moving relationship in the film is actually between Neff and Keyes. It’s not a romantic pull, but rather one of two people who respect one another. Keyes has worked with Neff for 11 years, and recognizes him as the best salesman in their office, while Neff, though he will be betraying Keyes, has enough respect for Keyes to know that he will be the biggest obstacle Phyllis and he face in trying to pull off this scheme of theirs. Is this another subversion by Wilder? Near the end, while Neff is dying of a gunshot wound, he tells Keyes that the reason he couldn’t figure this out is because it was too close for him, because the person he was looking for was at the desk across from him. Keyes says, “Closer than that,” to which Neff says, “I love you, too.” Was Wilder trying to bring a male romance into the cinema during the Hays Code era of the ’40s? I don’t think so, but the dynamic he, MacMurray and Robinson hit upon between these two characters is important to the way the film plays out, because the more we see of Stanwyck’s Phyllis, the less we want to see Neff tangled up in her web. The more that Keyes finds out as he’s trying to sort through this case, the more Lola (Phyllis’s stepdaughter) thinks her stepmother has now killed both of her parents, the more we want Walter to wake up from this fantasy he’s gotten himself into and leave her alone. Phyllis is simply greedy, someone who wasn’t going to get the fortune she thought she would from her husband, and in Walter, found a way to do kill two birds with one stone, and found someone who could help facilitate it, as well. More importantly, she found someone willing to facilitate it. Could Walter have resisted? Maybe if his first glimpse of Phyllis wasn’t with her just in a bath towel, but that’s how simply things can start in film noir. Fate catches you on it’s terms, not yours, after which, you are hooked. By the end, though, Walter has accepted his fate, which is why he’s confessing for Keyes to hear. His confession is the first thing we hear in “Double Indemnity,” with the rest of the film leading us to that moment. That the tale he weaves after that opening is just as tantalizing as those first shots is a credit to how gifted a storyteller Billy Wilder was. We can’t stop watching, even as the film leads us down a dark path. In that way, we’re very much in the same situation Walter is, with Wilder’s film acting as Phyllis does, tempting us with possibilities we normally wouldn’t even consider.