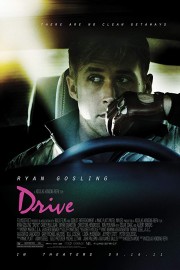

Drive

If you’re an action junkie expecting another “Transporter” or “Crank,” stay away. Stay far away. Or at least, do your homework before going to see “Drive.” After all, the film deserves to clean-up at the box-office, and who knows, maybe even get some Oscar nominations in the process.

In the driver’s seat is Ryan Gosling, who plays a stunt driver who moonlights as a wheel man for criminals. He gives you five minutes; if something happens in those five minutes, he’s all yours. Outside of that window, you’re on your own. Like Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name, Gosling’s character is simply known as, Driver. Yeah, it’s a pretentious move, but I’m betting you won’t care once the story gets going. Driver lives a solitary life that gets complicated when he meets Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her young son, Benicio (Kaden Leos), who live down the hall from him. The stoic Driver, who also works as a mechanic for his mentor and friend (“Breaking Bad’s” Bryan Cranston, who brings a fatherly grizzle and gravitas to one of the film’s many Oscar-worthy performances), becomes a friend to mother and son. Things become complicated, however, when Irene’s husband (and Benicio’s father) gets out of prison, especially when Driver comes across father and son after dad (played by Oscar Isaac) has taken a beating from some people he owes money to. Since the sins of the father could lead to consequences for mother and son, Driver intervenes.

Here’s the dirty little secret about action in movies: in the best ones, the action is the least interesting part. Most of Hollywood would disagree, but I’m sure most people reading this will side with me in saying that the action is dull if the consequences of the action aren’t intriguing. The best filmmakers understand this: John Woo built a reputation on it with his Hong Kong epics, and were he still interested in working in Hollywood, would have turned “Drive,” based on a novel by James Sallis, into another classic. Michael Mann is another filmmaker to whom the consequences of violence are more interesting than the violence itself; just look at his recent classics like “Heat” and “Collateral” or the ’80s crime stories he built his reputation on, like “Manhunter” and TV’s “Miami Vice.” And no filmmaker understands this idea greater than Quentin Tarantino, whose films use violence to test the characters and challenge their worldviews; like “Drive’s” director, Nicolas Winding Refn, QT is a movielover who absorbs film history into the DNA of his work, but comes out with something completely fresh and innovative.

“Drive” is all about the consequences of violence, and action, which– by the way, Hollywood –aren’t necessarily the same thing. Violence stems from action, be it a heist gone wrong or something more subtle, like agreeing to help someone out of a jam. Refn, in his Hollywood debut (which earned him the Best Director award at Cannes), understands the nuances of this philosophy perfectly, making the moments of violence in his film (from the aforementioned heist to Driver’s pummeling of a hit man in an elevator) land with a real emotional impact. There is no gratuitous bloodshed in “Drive”; it all serves a purpose in tightening the noose on Driver as he moves outside the comfort zone of his solitary life.

While violence drives the narrative, style drives the movie. The cinematography by Newton Thomas Sigel (“The Usual Suspects,” “X2”) paints Los Angeles as a city of shadows, even when it’s daytime. And the score by Cliff Martinez (“Solaris,” “Traffic”) is one of the year’s best, harking back to those great Mann films of the ’80s with a propulsive, synthesized mood matched perfectly by the songs Refn’s uses, which also capture that ’80s vibe effortlessly. And when both of those elements mesh with the editing during the film’s two great car chases (one right off the bat, the other during the aforementioned “heist gone wrong”), well, let’s say it’s been a good long while since Hollywood’s provided this kind of jolt of excitement in watching one car get away from another one.

All this being said, however, it’s the performances that energize “Drive” past its more generic cousins in the genre. Gosling continues his reign as one of Hollywood’s best young actors in a performance that reminds one more of his Oscar-nominated work in “Half-Nelson,” or his shamefully ignored turn in last year’s “Blue Valentine,” than his studio-sanctioned performances in “The Notebook” or this summer’s “Crazy. Stupid. Love.” While Mulligan and Leos are saddled with underwritten roles, they nonetheless come to life when on-screen with Gosling and Isaac, who isn’t your typical “lover just out of prison,” but rather, a good guy trying to make things right by those he loves. Still, it’s the older players in the narrative that shine brightest. Cranston I mentioned earlier, but I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Ron Perlman and Albert Brooks as partners and LA crime bosses. Perlman’s a bit lower down the food chain than Brooks, but his gruff look and powerful voice makes him a menacing presence. It’s Brooks, however, who runs away with the film’s top acting honors. This isn’t the neurotic comic genius of “Mother,” “Defending Your Life,” or the father fish in “Finding Nemo,” but something else entirely; not even his work in Steven Soderbergh’s “Out of Sight” can prepare you for what to expect from Brooks’s Bernie Rose. His menace and pitch-black wit seems to come from the darkest place imaginable, especially when his whips out a blade. Driver really got in over his head when he met this guy. Still, the images of Brooks and Gosling discussing a truce in an empty Chinese restaurant, after both have bloodied their hands, are among the most memorable of this year, although it’s what happens next that will linger longer in the memory, and ends “Drive” as it began, with a loner driving down the dark LA streets, not sure of where the next few minutes will take him.