Fahrenheit 9/11

Originally Written: October 2004

In “Fahrenheit 9/11,” Michael Moore never states that Saddam Hussein is a bad guy. Does he really need to? I think most of us who have been alive the past 20 years- and are old enough to remember the first Gulf War in particular- would kind of agree that that is the case. No, we didn’t live in Iraq under his reign, but we’ve been told enough over the years to where it’s pretty obvious we wouldn’t necessarily want to. In “Fahrenheit 9/11,” though, Moore shows us footage of Iraqi children playing in the streets, and the people of the country going about their everyday lives before the US and the Coalition of the Willing began bombing the country in March of 2003 in their attempt to disarm Iraq, which- as it turned out- didn’t need to be disarmed in the first place, despite the frequent assurance by the Bush Administration that they did in fact have weapons of mass destruction. Critics of “Fahrenheit” have called Moore out, criticizing his decisions on both counts, saying it doesn’t give us an acceptable vision of what the country was like under Hussein. Fair enough, but that’s not why he makes the choices. His reasons are two-fold: 1) As mentioned previously, he doesn’t feel like he needs to say what’s already widely known, that Hussein is someone who does not deserve the power he had. And 2) Moore gives weight to the senseless loss of life war creates, even if it isn’t on the side we’d like to focus on, or that the media wants to focus on.

In “Fahrenheit 9/11,” Michael Moore never shows us the tragic events of September 11, 2001 (though we do hear the sounds and see the shocked reactions), which led us into the War on Terror that began in Afghanistan- which still sees troops deployed in it- and continued to Iraq, which has been proven to have no links to the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and little or no link to Al Queda. Does he really need to? I think all of us who watched TV on that day three years ago will never forget what we saw that day, or how we felt. We don’t need a reminder of what happened. By focusing instead on the moments immediately after the attacks, as opposed to showing us- for the thousandth time- the actual event, Moore reminds us of the emotional toll on the country 9/11 had, and reminds us for who our leaders claimed they were going to war for. Have those who lost their lives- and those who were left behind- been forgotten as the War on Terror has raged on? I think to an extent that they have. If there’s a more tragic after effect of 9/11, I don’t know what it is.

In “Fahrenheit 9/11,” Michael Moore shows the images of US troops in Iraq we only just saw this year. The humiliation of prisoners taken by troops. The loss of life, on both sides. The disenfranchised feelings of soldiers who are over there. By showing us these images, Moore risks turning his audience against our military. Instead, he turns us against the war, as we realize these soldiers are just doing as they are told from their superiors, whether they wear uniforms of their own or suits and work in Washington. This is how they’ve been trained. Is it what they’ve been trained to do? In a general sense, yes. In a more specific sense, I don’t know if they would completely agree with that.

In “Fahrenheit 9/11,” Michael Moore shows us the consequences of blind faith in our politicians, and that they maybe aren’t as truthful as they should be. In 2000, well, the country knows who it voted for. But what it may not know is what Moore has to say, about how Bush and co. were able to steal the election from not just Al Gore but the American people (further evidence is in Moore’s excellent novel “Stupid White Men”). If you didn’t think so before (I did), there’s no way you can’t after Moore shows you what he’s found out.

In the days after 9/11, Bush was a real leader, or at least he acted like it. I felt it; I even felt a bit safer, more so than I thought I would have if Gore were president. In the months before and years since, I haven’t thought so. He’s talked tough, but something’s been missing. The words lacked meaning. And in many cases, they’ve lacked truth. I won’t go into that; I’ll let Moore and “The Daily Show”- the only breaths of fresh air in the political media- point that out. In not only his speeches, but those of his Administration officials, he’s been hammering home the same points, and the more he’s been doing it, the less I’ve believed it.

As the poll numbers have shown, many Americans haven’t let go of that feeling I had about Bush after 9/11. For Moore, that’s unacceptable, and in every frame of “Fahrenheit 9/11,” he makes his point with compassion, anger, and his trademark sarcasm (you gotta love his opening voiceover, which begins with “Was it all just a dream?” as we see Gore celebrating a victory in Florida in 2000). That last part is important; without it, “Fahrenheit”- like his previous films (1989’s “Roger & Me,” 1998’s “The Big One,” and 2002’s Oscar-winning “Bowling for Columbine” are all classics and unmissable)- would fall into despair under the weight of the tragedy that’s unfolded. Instead, it turns “Fahrenheit 9/11” into a powerful and thoughtful provocation that is unforgettable, regardless of how you see its’ politics. Credit Moore for finding the strength to be able to crack wise and find the humor that balances the pathos Moore finds in his images. The sight of Bush sitting firm at his Florida school photo-op as the Twin Towers were in flames thousands of miles away. The revelation that no one in Congress read the US Patriot Act before it was approved. The conversations with Lila Lipscomb, a patriotic mother in Flint, Michigan (Moore’s home town), whose son died in Iraq (“Fahrenheit’s” most paralyzing sequences chronicle Lipscomb’s change-of-heart towards Washington). The absurd levels of fear pumped into our national consciousness by our new Homeland Security measures (and the odd realities of said measures). The reminder of the wall that was formed in New York after 9/11 for people searching for loved ones feared lost in the attack. Moore’s desperate, tragi-comic attempt to enlist congressman’s children into the military with the help of a disenfranchised Marine. Moore’s final voiceover, which honors our military men and women and quotes Orwell, who gets to the heart of war by saying that it’s not meant to be won, but to be continuous. All moments that last long in the memory; each for a different reason.

In “Fahrenheit 9/11,” Michael Moore is waging his own war. A war against the hypocrisy of an administration (and politicians in general); against the needless loss of our brave men and women overseas; and against the disintegration of free speech in a country that preaches such expression (it’s our First Amendment for crying out loud), but is forced to suppress it if it means saying something that goes against those in control, be it politically or of what we see on the news on a daily basis.

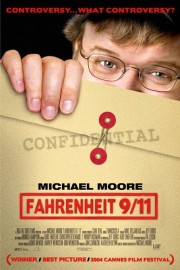

It’s this last war Moore found himself fighting when Disney- who wrote the checks for the movie via Miramax Films- left him homeless by choosing not to release the film. When conservative talking heads and organizations threatened protests and bans at theatres who showed the movie. When Lions Gate Films- in conjunction with Miramax’s Weinstein brothers (who are credited as executive producers)- took on distribution after the film won the Palm d’Or- Best Picture- at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. When a complaint was filed with the FEC to ban all ads for the film during the final months before the election, on the idea that the film was anti-Bush propaganda, not a movie (folks, it’s both, and I’ve seen worse attacks in actual political commercials). To date, “Fahrenheit 9/11” has earned $118 million at the box-office (ironically, more than any movie Disney has earned this year so far), has been released on DVD in enough time for this November’s election (the DVD is a must), did not see significant protests or bans against most theatre chains when it was released on June 25 (if it did, I didn’t see it), and in a weak movie year, it seems a lock- deservingly- for the first-ever nomination for the Best Picture Oscar for a documentary (it would be a lock for a second Best Documentary Feature Oscar for Moore, but they chose not to submit it for consideration).

I’d say that it’s a war Michael Moore has won. And so long as he continues to fight it through his books and movies, I’ll be standing side-by-side along with him.