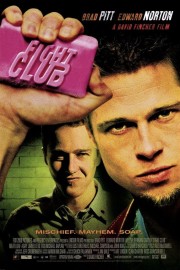

Fight Club

Would you believe me if I said that “Fight Club” was David Fincher’s gateway film to the more mature side we’ve seen in “Zodiac” and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button?” Some wouldn’t-Roger Ebert being one-but the more you watch it, the more you see a fluidity of visual language and storytelling that is the work of a mature filmmaker. “Alien 3,” “Se7en,” and “The Game” are still the work of a music video director (albeit, a very talented music video director). So is “Fight Club,” but here, the visual style is less chaotic. The themes take front and center over any sort of “story.”

What are these themes? The evils of consumerism. The self-discovery of the terminally-depressed. The narcissism of a generation that thinks their generation is the most fucked-up one. These aren’t questions; these are the themes that come through most when I watch the film. It’s one of the darkest comedies any major studio has ever released.

It’s also one of the best films of the past decade or so. Fincher and screenwriter Jim Uhls have a tricky story to tell; Chuck Palahnuuk’s book is a complicated critter from a narrative standpoint. The main character has no name, speaks to the audience as much as an outside observer than as a protagonist. Edward Norton was the perfect choice for the narrator, who takes the name Jack from a series of articles written about body parts. My favorite observation? “I am Jack’s colon.” “Yeah, I get Cancer. I kill Jack.”

But at some point, the film becomes the story of what happens when a simple idea gets too big and full of itself. Like the idea of consumerism, Fight Club-started by the narrator and Tyler Durden, a kindred spirit played by Brad Pitt in one of his best and boldest performances-grows into a cult that becomes a fanatic organization. Hmmm…sound like anyone you know? Whether it’s Al-Qaeda, the Nazis, or the Tea Party, all it takes is an idea, a few mindless automatons, and a leader who will put the two together into a movement. The narrator doesn’t know it yet, but Fight Club is just what he needs to cure his insomnia…

For me, the scene that stands out most, and crystallizes the fundamental arc of the film, comes after Tyler gives his disciples their first “homework” assignment- pick a fight with a stranger. The narrator chooses his douche of a boss. He goes in under the pretense of blackmail. When he doesn’t get what he wants, he begins to hit himself in a tour de force that Norton pulls off brilliantly. This is a critical scene, and as the narrator will discover, it’s an act more apropos to the assignment than he realizes. “It’s called a changeover. The movie goes on, and nobody in the audience has any idea.”

But beyond its thematic reach, however, Fincher’s film is a landmark of visual design. Rather than the shaky-cam that was so evident in his first three films, Fincher uses visual effects and Jeff Cronenweth’s cinematography to create a bold and stylized universe that is breathtaking to watch in its murkiness (designed by Alex McDowell). The camera weaves in and out of crowds and houses (and garbage cans), with editor James Haygood delivering a master class in storytelling finesse. Seriously, few movies are so complicated in story. How you get through it all with your mind intact is a credit to director and crew (which includes The Dust Brothers, who provided the pulsating, propulsive score).

There’s so much more I haven’t even discussed. Helena Bonham Carter’s trashy, but funny Marla Singer, whose relationship with the narrator and Tyler gets, well, complicated. Meatloaf Aday’s Robert Paulson and those “bitch tits.” And the fact that yes, if you’re like one of Tyler’s “space monkeys,” it’d be very easy to misinterpret the film’s purpose. That’s where real enlightenment comes into play, and why, sometimes, like the narrator discovers, all we need is the barrel of a gun in our mouths to realize just how fucked up our outlook on life has been. It’s how we take aim at such moments that will show us how tough we really are.