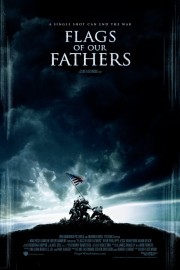

Flags of Our Fathers

Because of the film’s expanded scope, it’s not too shocking that Clint Eastwood’s “Flags of Our Fathers” doesn’t feel like an Eastwood film. We’re used to more intimate character studies from the actor-director, a two-time Oscar winner for the latter for “Unforgiven” and “Million Dollar Baby” whose accomplished filmmography also includes “Mystic River,” “A Perfect World,” and the underrated (in my opinion) “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil,” among many others I have yet to see. But looks can be deceiving, and though his film adaptation of the novel by James Bradley and Ron Powers (scripted with intelligence and reverence by ex-Marine William Broyles Jr. (“Jarhead”) and “Baby’s” Paul Haggis (an Oscar-winner for “Crash”)) is epic in its’ staging of the battle scenes, which would play like “Saving Private Ryan”-lite if its’ director (Steven Spielberg) wasn’t a producer on this film as well, Eastwood follows in Spielberg’s footsteps ably, filming a recreation of the Battle of Iwo Jima with the same virtuosity and brutality in “Ryan”…

…but something feels off about Eastwood’s approach. Whereas Spielberg made an immediate connection between the audience and characters as they were storming the beaches of Normandy, Eastwood’s staging of the battle feels impersonal, detached. He’s got the chops for this type of epic filmmaking to be sure (and Kubrick’s “Full Metal Jacket” was brilliant detached from the action), but he doesn’t quite seem comfortable with it, trying to blend his interest in the character’s stories with a grand scale. It doesn’t quite work (Kubrick at least made a connection of his own with the characters in “Jacket”), but at 76, you applaud Clint’s desire to push himself as an artist, as if he still had something to prove (he doesn’t). More on that later…

Once his film hits the mainland, however, Eastwood finds his footing, and “Flags of Our Fathers”- with a score by Eastwood (with assists by some of his long-time collaborators) that rates high with his moody and mournful musical efforts for films like “Baby” and “River”- becomes essential viewing for history fans and fans of not just war films but film in general. It’s here when the narrative- which intercuts deftly between both the battlefield and the fundraising trail (at the least, expect an Oscar nod for editor Joel Cox)- finds its’ most ambiguous and fascinating explorations in morality, with John Bradley (Ryan Phillippe, continuing to impress with supporting roles like this, “Crash,” and “Igby Goes Down”), Rene Gagnon (Jesse Bradford, from “Bring It On” and Soderbergh’s “King of the Hill”), and Ira Hayes (Adam Beach, from “Windtalkers” and “Smoke Signals”) thrown into the public’s eyes as heroes by a government in desparate need of funds from war bonds if they are to maintain their troops during WWII. They are the three surviving members of the group of six soldiers who raised the flag from the iconic photo taken atop of Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima- the other three died in battle.

The picture was a rallying point for a skeptical nation and a boon to the government, who send John, Rene (played with public confidence but private doubts by Bradford in a solid reminder of his neglected talent), and Ira (Beach, building on strong performances in “Windtalkers” and “Signals,” finds a soul irreperably scarred by war and guilt in a powerful, Oscar-worthy performance) on a nationwide tour to drum up sales of bonds so they can end the war. Rene’s the only one who seems to conform to government mouthpiece nicely (though his fame-eager girlfriend/fiance seems to facilitate that image more), but none of them feel the call of duty when they’re away from the battlefield. For one thing, there’s was the second flag raised that day (the first raising wasn’t photographed, though you can see it come down in the full photo), ordered up after a government official demanded they get the original one raised. For another thing, there’s the confusion that arised in private over who exactly was in the picture- the papers and government said one thing, the soldiers know something else. And then there’s the simple fact that they don’t see the heroism of being paraded around for raising a flag while their comrades in arms are still fighting the good fight on the battlefield (though only Ira expresses a desire to go back). And that they’ve seen the horrors there fellow soldiers are facing in the trenches on that island- glimpses of what the Japanese soldiers did to captives are indelibly chilling- doesn’t make the pain of being away from them- which stays with each soldier for the rest of his life- any easier. That pain is what drives the film dramatically, whether it’s on the battlefield, on the press tour that followed, or in the last stages of life for each of the three soldiers whose story is being told with such elegant feeling by Eastwood.

Inspired by “Fathers,” Eastwood pushed himself further with this film, as he and Haggis researched the Japanese point of view of Iwo Jima, resulting in a companion film to be released in February entitled “Letters From Iwo Jima,” starring- among others- “The Last Samurai’s” Ken Watanabe and featuring Japanese with subtitles. Not a new trick for a director (see Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” and forthcoming “Apocalypto”), but at 76, Eastwood is more relevant a director than ever. A lot like his protagonists in “Fathers,” I’m sure he would want us to hold our applause. That doesn’t make it any less cheerworthy, however.