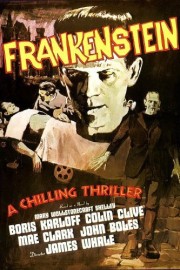

Frankenstein

James Whale’s “Bride of Frankenstein” towers so far above its predecessor in both force and feeling, that it’s very easy to forget how potent his original, 1931 adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Victorian Gothic novel was to begin with. I almost psyched myself out as well, almost changing this week’s “Movie a Week” to the latter film before realizing that Whale’s original vision of gods and monsters deserved its due. It still falls behind its 1935 sequel, but the film remains riveting and haunting, even if it was just a stepping stone to something much greater.

As I mentioned in my review last week of “The Revenge of Frankenstein,” among the most fascinating aspects of comparing Universal’s “Frankenstein” films with those from the Hammer studio is the directions the franchises took. With Hammer, their fascination became Dr. Frankenstein himself, with the exploits of his monster being secondary (no wonder, as they had the great Peter Cushing playing the good doctor); with Universal, the main protagonist was to become the monster itself, played by Boris Karloff in a performance of silent, misunderstood power. This would be more evident in the sequels, especially “Bride,” but once we see Karloff for the first time, we can’t take our eyes off of him. And when the Monster escapes, and is confronted with people, we see a character trying to assimilate into a society that fears him, especially when he mistakenly kills a girl who just wants to play.

Also distinguishing the two franchises of this story is the visual style. In Hammer’s “Frankenstein” films, the look is inspired by the old-Europe, Victorian sensibilities that Shelley was familiar with as she wrote the novel. Universal and Whale, however, were inspired by more contemporary sources. The influences on Whale appear to be more of the German Expressionist and Surrealist movements that had crept into silent horror movies of the previous decades of cinema; in particular, Dr. Frankenstein’s castle in which he brings his creation to life feels more in keeping with the architecture audiences saw in “Nosferatu,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and in particular, “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” which even now remains one of the most original and powerful visual experiences in horror. And the opening sequences of the doctor and his loyal assistant, Fritz, finding bodies for their experiment, feel artificial and staged, but not in a way that hurts the film artistically; that artificiality helps create a wholly unique universe for the story to exist in, allowing Whale to create one of the most distinctive and haunting visions in all of horror cinema. However, as later films would show, Whale’s contributions to the genre would be far greater, and longer-lasting, than simply creating the first, great adaptation of a storied classic. But that’s for another time.