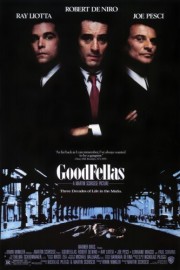

GoodFellas

If “The Godfather” is the Shakespearean tragedy of the American Dream, as many people have said, then Martin Scorsese’s “GoodFellas” is the reality of that tragedy. “The Godfather” plays like a work of fiction (yes, it is, but still). “GoodFellas” is the one that tells us like it really is, and sometimes, it’s not a pretty sight.

And yet what joy comes through in Scorsese’s telling of the true story of Henry Hill’s rise and fall in the mob from the ’50s to the ’80s- when he went into witness protection. The classic scene of Henry and soon-to-be wife Karen (Lorraine Bracco) walking into the Copacabana nightclub through the kitchen is its’ greatest distillation of this joy. It’s a single shot, composed by Scorsese and his great cinematographer Michael Ballhaus with the sole purpose of showing how the world has seemingly opened up to Henry because of who he is associated with. You can simply watch this shot repeatedly, and let the film’s greatness wash over you. No other scene shows Scorsese at the peak of his powers, displays his complete passion for the power of movies.

His masterstroke is the use of narration by Henry (Ray Liotta) and later, Karen, to tell their story. Voiceover is a tricky thing to use well in the movies- all too often it’s used as a crutch for lazy storytellers. But “GoodFellas” is one of the rare great films that finds an original and invigorating way to enhance the storytelling by letting us into the main character’s psyche (“Watchmen” and “Adaptation.” are two other examples). It also gives authenticity to the film by bringing the action down to a personal level of memories remembered of a life lost.

Based on Nicholas Pileggi’s book “Wiseguy” (adapted with the author by Scorsese), the film is paced and shot like a thriller, as Scorsese follows Hill from his childhood days working “part-time” at the Cab Stand across the street from his parent’s house to his rise as a foot soldier to mob boss Paulie Cicero (Paul Sorvino) to his lowest point when, in 1980, he’s forced to go into witness protection to avoid getting killed when he’s busted for drugs.

The film tells Henry and Karen’s story in the first person, but the real “heart” of the film is the friendship between Henry, mob enforcer Jimmy Conway (Robert DeNiro, in one of his best and coolest performances for Scorsese) and hothead Tommy (Joe Pesci in his brutal and brilliant Oscar-winning performance). We see Henry and Tommy introduced by Jimmy when they’re kids, and from that point they’re practically inseparable. We see them planning and pulling off scores like a $400K Air France heist and a multi-million dollar score known as the “Lufthansa heist,” as well as having to double back when Tommy kills a made man, and they have to dig up the body six months later.

That last one is responsible for so many of the key moments that elevates “GoodFellas” to greatness. The startling opening shots, with the three knifing the bloodied body in the trunk of Henry’s car. The wonderful scene when they go to Tommy’s mother’s to get a knife, and end up staying for a late dinner (the mother is played by Scorsese’s own mother in one of the most famous and memorable cameos in film history). And of course, the later retribution when the three think Tommy’s going to become a “made” man, but illuminates the harsh truth of their life- that at any time, at any place, it’s never safe to be complacent in how things are going. You can get whacked any time, for whatever reason, and someone somewhere will find out the truth.

Scorsese’s film is a film that is great art first, and great entertainment second, but it’s interesting to see the progression in reverse. The film starts out entertaining (from the dark wit of Pesci’s famous “How am I funny?” scene with Liotta to the intoxicating drive of the storytelling and the pitch-perfect lead performances by Liotta and Bracco, who make their characters as “average Joe” as any we’ve seen in the movies) and continues that way to the end (with its’ almost-frantic climax, following a day in the life of Henry before he gets busted), with Scorsese’s craftsmanship and the work of his collaborators (especially cinematographer Ballhaus and editor Thelma Schoonmaker) making art look easy. It’s not until the end that we realize that we’ve seen one of the great films of all-time, but only because it doesn’t insist on announcing its’ greatness at the outset. Just showing us how it’s done by going about its’ business.

Maybe if Hill had done the same, he’d still be in the life he loved and lived for from his early years. Now, he’s just a cautionary tale for others like him, immortalized by one of the great filmmakers of ours (or any) age. I guess there are worse fates, though. He could’ve ended up like Tommy.