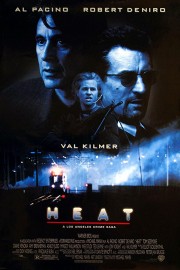

Heat

In a way, Michael Mann’s “Heat” is a genre deconstruction in line with Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven,” which looked at the Western through the eyes of a filmmaker who’d spent decades reinventing himself onscreen in the genre. For Mann, the time was about half that of Eastwood’s on film, but he’d spent some time on the beat in Chicago, so he knew the turf (and would continue to explore it in later films like “Public Enemies,” “Collateral,” and “Miami Vice”).

In “Heat,” Mann looks at the usual genre archetypes and traditions through fresh eyes and moral depth. The loose cannon cop whose personal life suffers. The career criminal who knows not to let anyone get too close to him. And the women who are unable to accept the way their men’s lives are.

That may make Mann’s film seem light on story for a nearly three-hour epic, but Mann has a lot of ideas to go around. It all starts with the balls-out heist of an armored truck at the beginning, scored with elegant minimalism and suspense by Elliot Goldenthal (and performed by Kronos Quartet), and shot with flair by master cameraman Dante Spinotti (who’s done some of his best work with Mann between this, “Manhunter,” and “Public Enemies”). The sequence sets up Neil McCauley (Robert DeNiro) and his crew perfectly. They have their shit together, they know their roles, and they don’t make a mess. Well, not until some trigger-happy cowboy named Waingro (Kevin Gage) offs one of the guards, turning a simple score into a clusterfuck.

The mistake of not taking out Waingro when he has the chance resonates throughout the entire film, as Neil and his crew- including Chris (Val Kilmer, superb), Michael (Tom Sizemore, hard-hitting), and Trejo (Danny Trejo)- find their jobs harder once Vincent Hannah (Al Pacino) is on their case. Mann could’ve just made this your typical crime thriller, but he’s looking at a much larger canvas- he’s looking to show how these career cops and criminals are in fact, two sides of the same coin. This is a theme that’s become prevalent in many a film afterwards (see “The Departed,” “Face/Off,” and “The Dark Knight” for the best examples), although it’s not to say that it wasn’t there before.

This idea is best exemplified in one of the quietest moments of the film, when Vincent and Neil are sitting at a table, drinking coffee. Both already know the other’s histories, and they both know how good the other is at their job. There’s a mutual respect the two share for one another, although they aren’t afraid to admit, that when push comes to shove, the other is going down.

Not long after that, both will be pushed to the brink when a bank heist- masterfully filmed and executed in performance and direction- turns into a bloodbath on the streets of L.A., and the story into a race against time- for Neil to get out of town (with or without the woman he’s fallen in love with (Amy Brenneman’s Eady), as well as a few loose ends to tie up), and for Vincent to find Neil before he takes the next flight out of town.

Part of Mann’s accomplishment in this and his other films is to surround his stars with character actors and other stars capable of creating an emotional connection between the audience and the character, regardless of what side they’re on in the end. And “Heat” is an embarrassment of riches. Natalie Portman is unforgettable as Vincent’s quietly troubled step-daughter with third wife Justine (Diane Verona, whose haunted look and biting dialogue helps define their marriage). Ashley Judd shows strength and vulnerability as Chris’ fed-up wife Charlene, whose affair with a Vegas businessman (Hank Azaria) gives her and son Dominic an out when the bank heist goes South. Jon Voight is his usual superb self as Neil’s fence. William Fitchner is sleaze personified as a brutal businessman who reneges on a deal with Neil. And Dennis Haysbert (“24’s” president) is tragic and poignant as Donald, who’s out on parole and working a crap job at a restaurant when Neil needs him for the bank job.

Watching the film today, Mann’s achievement is seeing this never-ending back and forth between cops and criminals from all sides, showing the emotional tolls on lives beyond simply life and death, of the lives of everyone involved with the life they choose. In this way, the film goes deeper than even the greatest crime dramas (your “Godfathers,” your “GoodFellas,” your “White Heats” and “Pulp Fictions”) have gone in the past. It helps that Mann aligns himself with people on both side of the law for research, resulting in a more organic feel than we’re used to. This isn’t just another Hollywood crime saga; it feels closer to something based on a true story.

Fact or fiction, however, one thing that can be said about Mann’s masterpiece is this- it’s unquestionably a true cinematic classic, regardless of genre. Of course, at the heart of it all are two of the greatest actors of all-time, who finally got to share the screen for one iconic moment (though both were in “The Godfather: Part II,” neither were in the same scene together), but- masters that they are- just played it like another day at the office. But even for someone who’s a bit of a “fair weather” fan of the two, even I could tell that there’s something special happening when Pacino and DeNiro share the screen in this film.

It’s moments like those that make it exciting to be a film fan.