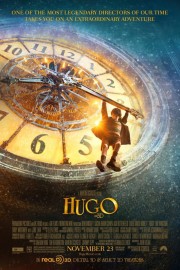

Hugo

Like any great fairy tale, Martin Scorsese’s “Hugo” has moments of profound sadness. It also has moments of pure delight. And most importantly, one wishes it were 100% true, but as one main character says, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.”

Movies, and the legacy of cinema, are at the heart of Scorsese’s film, which he adapted from the award-winning book, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, by Brian Selznick. Selznick, it should be mentioned, is the first cousin (once removed) of David O. Selznick, the iconoclastic producer of such films as “Gone With the Wind,” “Rebecca,” and “Duel in the Sun.” That last one was particularly important to Scorsese growing up: when he was four, his mother took him to see the film, which had been banned by the Catholic church his family went to. Though he wouldn’t understand the film until much later, the visuals seared into his imagination, and from that point on, the movies had Marty for life.

A similar story is told by young Hugo Cabret (the wonderfully affecting Asa Butterfield), the hero of Scorsese’s film. Orphaned after his clockmaker father (Jude Law) dies in a museum fire, and his drunken uncle (Ray Winstone), abandons him, Hugo finds himself alone in the world. Living within the walls of a train station in 1930s Paris, where he takes on his uncle’s job of maintaining the clocks so as not to raise suspicion, Hugo walks around the station, and often steals parts from a toymaker’s booth to try and fix an automaton (a wind-up robot that creates sketches) his father had brought home from the museum one night. Even with his father gone, Hugo has continued their mission to try and fix that automaton, thinking that within it holds a message from his father. His father, who, like Scorsese’s father, took Hugo to the movies all the time; for them it was a bonding experience. Hugo’s father often told his son about his first moviewatching experience, wherein a rocket crashed into the eye of a man on the moon; he likened it to his dreams coming to life.

That film, as any cineaste worth their weight knows, is the 1902 film, “A Trip to the Moon,” by Georges Méliès, the French inventor who, in close to 500 movies, helped pioneer the early use of special effects in cinema. Méliès (played by Ben Kingsley in an award-caliber performance) plays a pivotal role in “Hugo”; he turns out to be the toymaker Hugo has been stealing from, and as Hugo will learn, it was Méliès’s automaton his father brought home those years ago. It’s when Méliès’s goddaughter, Isabelle (the luminous Chloe Grace Moretz, continuing to impress), and Hugo become friends, and Isabelle is wearing a key around her neck that seems to go with the automaton, when both children discover the truth of who this old man, whom Isabelle has known mainly as Papa Georges, is, and the legacy of invention he left the world, and mysteriously abandoned.

Film history is deep within Scorsese’s DNA; anyone who has seen his extraordinary documentaries about the great films (and directors) in America and Italy will know that. With “Hugo,” that remarkable love of cinema comes alive in a new and exciting way, as Scorsese channels the gifts of some of the filmmakers he has been most inspired by– Federico Fellini (“8 1/2”), Buster Keaton (“The General”), Charlie Chaplin (try not to watch the scenes of Hugo around clock gears without thinking of Chaplin’s “Modern Times”), and Vitorrio De Sica (“The Bicycle Thief”) come most to mind –into a film that, I can see, getting children of a certain age excited in film history, especially when, in a fantastic montage, Scorsese shows clips of films from the likes of Keaton, Chaplin, D.W. Griffith, and of course, Méliès. If his four-hour documentaries on film are graduate courses on the history of cinema, “Hugo” feels like a film appreciation class, but taught in a way that will leave the students hooked and ready to dig deeper into what Professor Marty has to teach us.

That my review of the film has moved into a more personal, and I hope, passionate, examination of the themes and emotions it brought up, than simply look at the film from the vantage point of its artistic qualities, that’s perhaps inevitable, as it tapped into my own obsession with cinema, an obsession that Scorsese, both as filmmaker and as fellow film geek, has been responsible for fueling over the years; besides, if you’re familiar with his collaborator’s previous work for Marty, the excellence of Robert Richardson’s rich, colorful 3D photography; Dante Ferretti’s superb sets; Howard Shore’s delightful, emotional score; and Thelma Schoonmaker’s spot-on editing will come as no surprise. Scorsese is one of the greatest of all filmmakers not simply for his command of film craft, but for how remarkably personal his relationship is to the material he brings to life, whether it’s a violent story of the streets like “Mean Streets” or “GoodFellas”; a more spiritual exploration like “Kundun” or “The Last Temptation of Christ”; or films that seem out of place with the rest of his work (I’m looking at you, “New York New York” and “The Aviator”), but actually tap into another vein of what drives him to make movies. With “Hugo,” Scorsese has made his most unorthodox film (and the first one that can truly be shown to children without shame), and arguably, his most personal one, as it tells the story not just of its main character, but also, is a reflection of the man who created it.