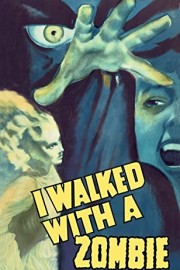

I Walked With a Zombie

Don’t get your hopes up if you are expecting a gaggle of brain-dead, flesh-eating corpses walking around in this 1943 thriller- this isn’t that type of zombie movie. Twenty five years before “Night of the Living Dead” would co-opt the word for one, specific purpose, director Jacques Tourneur told a story about the walking dead that focused on the psychological rather than gore and gorging on human flesh. That wasn’t the type of film that producer Val Lewton made during the ’40s, and the focus on emotional and mental terrors is what keeps the films he made remarkably fresh and watchable decades later.

As I brought up the credits for “I Walked With a Zombie” for the purpose of this review, I was a bit surprised to find an uncredited writing credit for Charlotte Brontë’s novel, Jane Eyre, under “adapted from.” The film’s title and story is taken from an article written by Inez Wallace, but apparently, Lewton (who was a story editor for David O. Selznick before he turned to producing) thought Wallace’s story was too cliched, so he adapted it to Brontë’s novel of Gothic romance. I’m guessing it’s just the structure of Eyre, because this revelation really threw me for a loop. This isn’t like Brontë’s story at all, but it is in keeping with my notion that some of the most exciting films to watch are those where not all of the references and inspirations are upfront and obvious, something that Lewton was quite effective at. His films, some of the most significant in the evolution of horror as a film genre.

The film is told from the perspective of Betsy Connell (Frances Dee), a young nurse who is being hired to look after a wealthy man’s wife, Jessica (Christine Gordon), who is in a fugue state. The man is Paul Holland (Tom Conway), who lives on an island in the East Indies. We first meet him as Betsy is on the boat that will take her to the island, and she is marveling (to herself) about how beautiful the sights are. Almost on cue, Holland verbally tells her otherwise- he seems to have read her thoughts. That’s the first of many unsettling things as Betsy adjusts to life as Jessica’s nurse.

This was the second film director Tourneur made for Lewton, the first being their classic thriller, “Cat People.” Neither film shares anything in narrative in common with one another, but what connects them is an atmosphere of foreboding that could not be written into the screenplay by Curt Siodmak and Ardel Wray. The images Tourneur puts on screen have a feeling to them that isn’t easily written on the page, starting with the sight of Holland and Betsy on the boat traveling to the island together- coupled with the exchange outlined earlier between them, the look of the scene takes on both outlooks at the same time. The first time we see Jessica walking at night, in a nighttime wardrobe that blows in the wind, with her head tilted slightly to the side, is disturbing, and gives us a barometer of what it’s going to be like for Betsy on this unusual job. And then, about midway through the film, Betsy takes Jessica to a voodoo ceremony taking place on the island; she is able to hear the drum beats from the Holland’s home, and sees that Jessica is drawn to them. The ceremony, which includes the ability to control people in a state like Jessica’s, is one of the most haunting stretches of film in sound-era horror cinema, staged beautifully by Tourneur and shot by his cinematographer J. Roy Hunt. From that moment on, the film dives headlong into the supernatural aspects that must have drawn Lewton to the base material in the first place, leading to an ending that almost feels anticlimatic given what we witnessed before, but is also keeping with Lewton’s notion, on display in all nine of his productions, that when dealing with the unexplained in life, happy endings sometimes come with a price. The characters aren’t as vivid in “I Walked With a Zombie” as they were in “Cat People,” but Tourneur makes their dilemma just as fascinating, and difficult to forget.