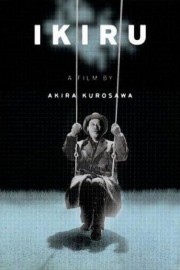

Ikiru

As with anything you might do in it, you get out of life only what you put into it. This is the sad truth Watanabe must accept in “Ikiru.”

He has just learned he has stomach cancer, although the doctor has told him it’s just a mild ulcer. In the waiting room, however, a stranger has told him exactly what the doctor is about to. It’s a haunting scene, and the body language of Takashi Shimura as Watanabe is what sells the horror of the scene, and the entire film. He’s worked as a bureaucrat for 30 years, but what has he really worked for? This is the question at the heart of Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 film.

Kurosawa was best known for his samurai epics, but a closer look at the best of those (“Seven Samurai,” “Ran”) and you see the work of a man always searching for a deeper meaning to life. In “Ikiru,” it’s the exploration of a man who, with nothing left to lose, finally figures out what it means to truly live. In fact, “Ikiru” translates to “to live.”

This is the type of film directors more usually make late in their careers, which makes Kurosawa’s perceptiveness (he was only 42 at the time, and would live to be 88, and still had many great films ahead of him) all the more extraordinary to see how in touch with he was with this type of emotional journey. But such realizations can happen at any time of a man’s life. The only thing that connects them is that great tragedy is required to put one’s life into such focus.

In 2007, I began my own such journey when I was hospitalized with pneumonia. I got to the emergency room with minutes to spare, I would later be told. When I finally woke up, I had been in a medically-induced coma for eight days. To lose that type of time was devastating. Now add almost 30 years to that, and that’s where Watanabe is coming from.

His journey is a difficult one. But the trouble with such personal and revealing emotional journeys is that you can’t really share them with anyone. Watanabe tries to talk to his son, but all he’s interested in is the money he’ll one day inherit. And no one at the bureaucracy knows but a young woman who needs his stamp to resign- rumors and speculations about what has happened to Watanabe will continue even at his wake, when his actions- leading to a drive to try and get a children’s park built- will perplex most but inspire one, who might be able to find his own way through life if he can figure out what drove Watanabe at the end of his.

So many scenes in this film stand out as classic. The night out with a drunken writer, who’s moved by Watanabe’s self-reflection, that culminates with a beautiful scene in a bar where the old man’s voice during a 20s ballad gets to the heart of his emotional plight. When his son and his wife come home late to find Watanabe alone in their room, with the lights off. Mortified, as they were talking about his money, they can’t begin to understand what was really going on with him as he cried himself to sleep that night. And then there’s the final half of the movie, set at Watanabe’s wake. Bureaucrats and family, wrapping their heads around his behavior over the last five months of his life, when he did everything he could to see that a children’s park was built on a piece of rundown land. Intercut with memories of his colleagues of his race to get the park built, we see them pose theories and uncertainties as they try to put themselves in Watanabe’s shoes, to uncover what only one seems to have the insight to uncover (and remember) what Watanabe found in himself those last five months, which is what it means to live.

And then, there’s the shot of Watanabe, at the park he saw through to the end, on a child’s swing, which is where he would be found dead. In a way, this shot- more than any other in the film- gets to the profound truth of the film. While no one else will know more than we do about how we tried to live, no one but us will know less about what was left behind in our death. Yes, Kurosawa’s film has immense sadness and profundity, but few films are more inspiring for what they try and tell us about ourselves.