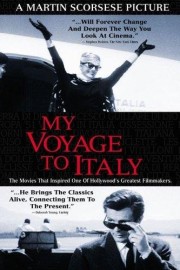

Il Mia Viaggio in Italia (My Voyage to Italy)

A few years after he made his exceptional 1995 documentary, “A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies,” Scorsese allowed us, once more, into his cinematic memory bank with “My Voyage to Italy.” Though it debuted in 1999, I wasn’t able to watch it until its premiere on Turner Classic Movies in 2002. Like “Personal Journey,” I was already enough of a film geek to be familiar with some of the films Scorsese mentioned in his four-hour journey into Italian cinema, but “Italy” opened the floodgates to world cinema in a way few other filmmakers have accomplished.

Like his earlier film on American cinema, “Italy” looks at both the best known filmmakers of the country– directors like Vittorio De Sica (“The Bicycle Thief”), Michaelangelo Antonioni (“La’Avventura”), and Federico Fellini (“8 1/2”), filmmakers (and films) that even casual observers of world cinema have probably at least heard of –as well as directors such as Roberto Rossellini (“Open City (Roma, Citta Aperta”) and Luchino Visconti (“Senso”). Never heard of those last two? You’ll never forget their names after Scorsese’s done. Even though I feel like Scorsese reveals a bit too much of the films he discusses in “Italy,” I’d be surprised if anyone viewing wouldn’t be inspired to at least seek out a few of them.

Even more so than “Personal Journey,” “Italy” shows Scorsese digging deep into his emotional memory bank. We learn about his life growing up in New York; we learn about his family, and even see home footage filmed in his youth; and we find out a great deal about the circumstances that led to him discovering some of these films. It’s a riveting look at a filmmaker for whom cinema has always taken on a form of confessional.

More than just the personal impact of some of these films, though, Scorsese sets the stage for the worldviews that led to the films he discusses. In particular, it’s his discussion of the post-WWII directors, especially Rossellini and De Sica, for whom the destruction of their country, both by war and fascism, led to the naturalistic and spiritual approach to filmmaking that became known as neorealism. Now, I’ve seen a few of those early neorealist films, and I can safely say that, if you’re worried that the films will be dreary and depressing, fret not– they’re as alive and entertaining than even the most predictable Hollywood melodrama. More so. And to see how these filmmakers evolved as their careers continued, it’s a thrilling look at how artists follow their own creative impulses, all the while staying true to their roots. The most fascinating subjects, as Scorsese explains it, are Rossellini and Fellini. Both took hits from intellectuals and other so-called “experts” of cinema, but seeing these two through Scorsese’s eyes makes for a gripping experience, whether you’re a budding geek or a long-time cineaste.

Both “My Voyage to Italy” and “A Personal Journey” have had profound impacts on me as a film fan; as a hopeful filmmaker; and as an individual simply trying to survive in this difficult world. These eight hours have given me more to think about with regards to how I look at cinema, and how I consider the careers of my favorite filmmakers. One of the things I think a lot of people make a mistake with in regards to cinema is in thinking flawed films are automatically devoid of “greatness.” But perfection is ellusive in cinema– even the greatest filmmakers miss the bullseye in one way or another, even in their best films –and flaws challenge us to see what a film really has to offer us. In “My Voyage to Italy,” Scorsese expands the notion of “greatness” in cinema by helping us understand that art is in the eye of the beholder. None of the films he discusses are “perfect,” but their impact on him, and his own films, is perfectly suited for what he’s had to say over the years. If I can honor the films that have inspired me over the years so profoundly, I’ll feel like I’ve accomplished something in my desire to leave my mark on the legacy of cinema, just as Scorsese has here.