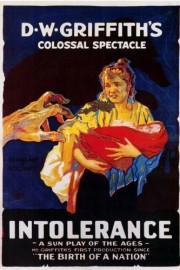

Intolerance

D.W. Griffith’s “Intolerance” remains one of the great spectacles of American cinema; in fact, all of cinema. True, there are a few epics that have surpassed it in scope and sweeping grandeur, but even the finest of those, I don’t think, have come close to matching the narrative importance Griffith brings to his masterpiece.

Watching it again, for the first time in several years, I found its message profoundly important for this day and age. In fact, I’d love it if every conservative who went to Wednesday’s “Chick-fil-a Appreciation Day” watched this movie (now available on Netflix Instant), whether they have already or not (I’m guessing not), and ponder its message condemning intolerance and bigotry over the ages. The problem with this notion, however, is two-fold: 1) the idea of getting most people on either side of the political spectrum to sit through a silent film is absurd; and 2) the idea of getting most people to sit through a 3-HOUR silent film is just plain silly. Still, that doesn’t make it any less of a dream of mine.

It’s curious to note that the main reason Griffith made “Intolerance” at all was to atone for the blatantly racist second half of his previous film, the landmark, “The Birth of a Nation.” Even though Griffith was unable to see the harmful racial stereotypes for himself, there were plenty around to point them out to him, including the NAACP, who continue to boycott the film (which gave rise to a second era of the Ku Klux Klan after they were depicted as saviors of the South in “Nation”) if people even consider showing the movie. Still, Griffith made “Intolerance,” and after seeing this and his 1919 film, “Broken Blossoms” (about the interracial love of a white girl and an Asian man), it’s plain to see that THIS is the real D.W. Griffith– once blind of his own prejudices, he had his eyes opened to injustice, and sought to preach for tolerance, love, and peace. He made a more poignant, emotional case in “Blossoms,” but he made a more thrilling, powerful one in “Intolerance.”

In “Intolerance,” Griffith tells four different stories that plead for tolerance. Now, that alone would have made the film revolutionary in the first two decades of cinema, but Griffith increases the degree of difficulty to have all four be from different eras of human history. The first, and most powerful, is from present day America (well, present day for 1916), where society matrons, hoping to impose “their” values on the community at large. The primary focus of this story, however, is on a young woman who falls in love with a man, has a child out of wedlock, and is deemed “unfit” when he goes to prison. This is intercut between the fall of Babylon (staged in a sequence that is all the more impressive considering it had to be done for real, without computer effects); the life (and death) of Christ (treated, in message, as seriously as it is in films like “The Passion of the Christ” and “The Last Temptation of Christ”); and an uprising in 16th Century France.

In “The Birth of a Nation,” Griffith brought together all of the cinematic techniques and storytelling tricks he had been experimenting with in his shorts– in particular, the idea of “cross-cutting” between events –and delivered a rousing narrative. Sadly, the indefensible choices he makes in the second half of that film make it almost impossible to appreciate this artistry. In “Intolerance,” however, Griffith perfects his blend of story and technique, and the results are exhilarating, and deeply moving. Even today, few filmmakers are as ambitious as Griffith was here in combining different narrative threads into a grand central theme. And that theme, as Christ says, is love thy neighbor. Throughout the film, we see a shot of a woman (Griffith’s muse, Lilian Gish) rocking a baby, accompanied by the words, “Out of the cradle, endlessly rocking… “. Whether it’s 1st Century Jerusalem, or Babylon, France during a religious revolution, or a young woman’s life in 20th Century America, the cradle of intolerance is always rocking. Our satisfaction in the film comes from the notion, which Griffith is unabashed in saying, that in the end, love and tolerance will win out in the end.

It’s nice in theory. Unfortunately, there will always be those who are, when challenged by the changing times, look to a doctrine of divide and conquer rather than unite and embrace. Almost 100 years later, not much has changed.