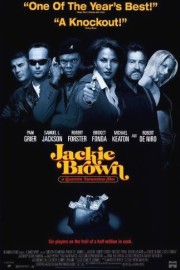

Jackie Brown

If “Pulp Fiction” was Quentin Tarantino’s stylistic masterpiece, “Jackie Brown” is his greatest piece of storytelling, making Elmore Leonard’s prose pop on-screen with a master’s touch, letting the characters and story breathe rather than rushing them through plot points.

I find myself going back and forth as to which is QT’s best film. “Pulp Fiction” is a thrilling original- a crime epic front-loaded with dark humor, great performances, and original thinking. But “Jackie Brown” is something wholly unique as well- a rich character study that rewards patience with unforgettable characters and a completely surprising unfolding of events that builds suspense out of the motivations and risks of its’ characters.

Let’s start with Robert DeNiro’s Louis. This is DeNiro’s best performance since the glory days of his collaborations with Scorsese. And Louis couldn’t be more different than his Jimmy the Gent, his Jake LaMotta, his Travis Bickle. Burned out after doing four years in jail, Louis is defined through his interactions with Samuel L. Jackson’s Ordell and- most especially- Bridget Fonda’s Melanie, a beach-bunny pothead who’s as flaky as Louis can be, and as smart-ass as Louis is loyal, a dynamic that’ll pay off handsomely when the deal starts to go down to get $500K out of Mexico for Ordell. If you’ve seen the movie, you know what I’m talking about; if you haven’t, you’ll know it when you see it.

But the heart and soul of the film is the relationship between Jackie and Max Cherry. Pam Grier was the reason for Tarantino’s adaptation of Leonard’s “Rum Punch”- he wanted to give the ’70s star of “Foxy Brown” and “Coffy” the role of a lifetime in the genre that made her a star. And Grier, one of the toughest actresses around, still has star power and range to play a role of such depth with an in-charge attitude, as well as a believable vulnerability that pays off as the suspense tightens and she tries to juggle all the balls around her- from Ordell to Michael Keaton as ATF agent Ray Nicollete to the exchange itself. How the Academy passed her over for Best Actress still has me scratching my head (same goes for Jackson’s ruthless Ordell, which lacks the redemptive contemplation of “Pulp’s” Jules, but is no less charismatic or unforgettable).

The Academy did nail it by at least nominating Robert Forster for his turn as Max Cherry. Forster was just the most recent star resurrected by Tarantino in his casting gifts; a more well-known actor might not have gotten so much out of this character. Cherry has to butt heads with Ordell, be the voice of calm and reason with Jackie, as well as be the character the audience finds itself in as all of this is going down, and Forster nails it on all accounts, especially when Max starts listening to The Delfonics after he and Jackie share a coffee after he gets her out of jail. There’s a longing stirred in the character that a lesser director would play for the simple reason to get these characters into bed. Thankfully, QT is above that, resulting in a satisfying emotional bond as rich and mature as anything he’s put onscreen.

But as with Tarantino’s other films, a lot of a film’s emotional heft comes from the soundtrack. Tarantino is a master scorer in using music in his films, and “Jackie Brown” is probably second to “Pulp Fiction” (and inches ahead of “Inglourious Basterds”) on that front. It starts and ends with Bobby Womack’s “Across 110th Street,” which might have fallen along the waste side were it not for QT’s keen ear. Listen to the lyrics as we see Jackie going to her job in the opening credits, and they tell you everything you need to know about this character without Grier even saying a word. Then listen to them again at the end as she drives off into the sunset of a new life. You couldn’t ask for a more emotionally satisfying ending, which is another thing Tarantino has become oddly adept at throughout his career.