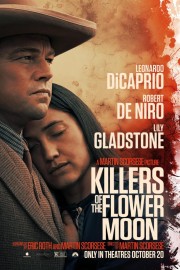

Killers of the Flower Moon

**This piece was written during the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strikes. Without the labor of the actors currently on strike, the movies being covered here wouldn’t exist.

It’s disheartening to see so much of the discussion of Martin Scorsese the filmmaker overtaken by people who see him as only a purveyor of “gangster movies,” a vulgar simplification that removes some of his best films (“Age of Innocence,” “After Hours,” “The Last Temptation of Christ” and “Silence”) from the conversation. If crime has become a preoccupation of his over the years, though, it’s because he’s fascinated by the ways people are taken in by a criminal lifestyle, and the ways it can ruin the souls of those people to where their mindset is forever changed. In “Killers of the Flower Moon,” one moment near the end exemplifies this brilliantly, and it’s a shame, because it negates everything Ernest Burkhart has said about his feelings for his wife, Mollie, as he starts to reckon with his actions. It’s up there with some of the best Scorsese moments, one that feels fresh in the hands of a master who has probably seen dozens of moments like it over the years, and seen how they succeed, and how they fail. Needless to say, everything he does is right in this moment.

The balancing act that Scorsese and his co-screenwriter, Eric Roth, have in adapting David Grann’s celebrated novel is not an easy one. Grann’s novel tells about the murder of Osage Indians over oil rights, and how the early FBI brought the crimes to life, in the early 20th Century, but it tells it from the perspective of an FBI agent. Here, Scorsese wants us to feel the perspective of the Osage themselves, and their sense of loss. It’s a balancing act that mostly succeeds, in part because of the performance by Lily Gladstone as Mollie, one of four women in a family who have headrights to the profits from oil deposits in Osage Nation in Oklahoma. She becomes the wife of Ernest Burkhart (played by Leonardo DiCaprio), the nephew of William King Hale, a political boss in the area who isn’t subtle about his desire to have as much of a share in the area’s oil profits as possible, and is not afraid to kill people to get it. Hale is played by Robert DeNiro, and for the film’s 206 minutes, what we watch is the soul of Ernest get corrupted by his uncle while he tells himself he loves Mollie and the family they’ve built.

As much as the allure of crime is a subject in many Scorsese films, so are the ways violent men rationalize their criminal behavior. Ernest has been brought to Oklahoma by his uncle after WWI under the guise of wanting to help him get back on his feet, but I think even before they see each other, King Hale sees Ernest as someone who would be a good soldier, and can be molded to do what he wants done. Early on, King Hale does what many other powerful men do, and give Ernest a job that looks legitimate, but also will lead to work that feels like a normal part of the position, but is criminal in nature. Hale recognizes that Ernest is a bit slow, so he has to spell things out for him at first, but Ernest is so ready to reward King’s trust in him that he goes along with it. What’s wild is seeing Ernest almost internalize Hale’s words as if they are his thoughts; we can see him basically feeling like he’s making choices on his own, even though we’ve heard Hale lead him in that direction. When we see Ernest try and scheme on his own, needless to say, it doesn’t go as smoothly as King’s plans, and will- in fact- be his ultimate downfall when a Bureau of Investigation agent (played by Jesse Plemons) comes into town at the behest of Mollie to investigate these murders.

Mollie is the heart of this film. A diabetic- something that was a death sentence at the time- she initially gets in Ernest’s car because he offers to drive her home. You can see the affection she has for him grow, though, but as they settle into marriage, she begins to suffer personal tragedy after personal tragedy that makes her suspicious. Osage people have been meeting sometimes violent ends that have a common trademark to them- their headrights to the oil profits in the land go to white spouses. And while the tribal council talks of wanting to have these crimes investigated, they are at the whims of white men who would rather not be looked in to, and to a certain extent, are only inclined to go so far so long as the community thrives. She acts not just because she has lost sisters and a cousin to violent ends, but because she sees her people almost corrupted to the point of erasure. The film begins with a startling sequence where we see an Osage ritual of the dead, including the burial of a pipe that represents the end of their culture. Scorsese and his cinematographer, Rodrigo Prieto, shoot the rituals of the tribe with a solemnity that Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing turns into poetry. Each Osage life taken is given a moment of silence before the narrative continues. For the film, Mollie represents the last hope Osage Nation has for justice as one by one, the white man’s world brings violence, vices, and corruption to their life. The character is basically a figurehead for the Osage as much as an individual with her own agency; I have mixed feelings on that, but I am not mixed on Gladstone’s performance, which is thoughtful but also very sly at times- her humanity is at the center of the movie, even if her character isn’t always similarly placed.

Finally, Scorsese’s iconic leading men are in a movie together. It was only a matter of time, and it’s interesting to see how they are used here. As King Hale, DeNiro is playing off of the iconography of his great mobsters for Scorsese- in particular, Jimmy Conway from “GoodFellas” and Sam Rothstein from “Casino.” Hale is constantly in charge, wheeling and dealing and we see in every major scene how King is making sure things move in a direction that keeps his interests safe over those of others- DeNiro thrives in this position, and while I don’t know if it’s up their with his best work, it certainly feels as exhilarating as his past performances for Scorsese are. As Ernest, DiCaprio continues to find different characters to play for Scorsese, and this might be one of his richest. The question we constantly find ourselves asking with Ernest is how much he is complicit in Hale’s criminal enterprises vs. how much he is being used. Certainly, he does awful things in King’s name in this film, but- as I said earlier- when he tries to do awful things on his own, his own plans are not quite successful. When he has to administer Insulin shots to Mollie later in the film, in a particular way, does he recognize what King’s motivations are in telling him to do it this way, or does he truly see himself as helping Mollie? I do think a level of amorality starts to take over Ernest as the film goes on, but one can see in his eyes that he does care for Mollie. Unfortunately, his uncle’s mentorship pulls him too far in the direction of amorality, leading to the ending I hinted at earlier. This might be DiCaprio’s best performance for Scorsese after his work in “The Wolf of Wall Street”; it may not look the same way DeNiro does, but he’s found a different type of criminal to illuminate for Scorsese.

“Killers of the Flower Moon” has so much it does well. The performances, the cinematography, the editing, the score (by the late Robbie Robertson, whose work gives this film an always-present sense of anxiety) and the vision of the film, as well. We’ve already seen amorality and greed over oil in “There Will Be Blood,” but one of the things that distinguishes Scorsese’s film is how it views it- in its own way- as a death sentence to the land as much as it is the people in the way of the greedy who want to control the profits. I love the formal challenges Scorsese puts in front of us as a viewer in how he tells this story, and the film’s wicked way it tells this story’s comeuppance. And yet, I feel like the passion to tell this story is at arm’s length from the audience in how Scorsese tells it. I certainly think he’s being respectful, but I also feel like- by centering so much on Ernest and King Hale, it unbalances how much we’re to engage with the way the Osage are under siege by white man’s corruption. That doesn’t make the film less the work of a filmmaker still pushing himself, though.