Les Vampires

In the span of a decade since the likes of “The Great Train Robbery” and “A Trip to the Moon,” filmmakers from all around the world had begun to expand the possibilities of cinema as entertainment and as a way of telling a story. One of the most daring examples is the 1915-1916 serial, “Les Vampires,” written and directed Louis Feuillade, which uses a combination of (mostly) invisible cinematic style and complex narrative to challenge the viewer, and push the boundaries of what film could do in it’s early days.

One of the many things that stands out about “Les Vampires” is, first and foremost, it’s narrative form. Rather than telling it’s story in one installment, “Les Vampires” is a serial, told in 10 episodes, which would have likely been spread out over a period of weeks (or maybe even months) to get audiences coming back to the theatre for the next installment. By breaking up the narrative into sections, Feuillade is incorporating the idea of chapters in a book to the medium of film, wherein each chapter tells a chunk of the larger narrative, but could also be capable of working on it’s own. This convention would later become an integral part of the moviegoing experience for decades, as theatres would show an installment of a serialized story before a feature film, and also give way to the rise of television as a storytelling medium.

In addition to it’s structure, “Les Vampires” is also influential in it’s genre. Although the title, and some of the language (as seen on title cards) hints at a horror story, “Les Vampires” is, in fact, a crime drama, and really, the birth of what we would call the “police procedural.” It’s hard not to watch Feuillade’s series, and not think of TV shows such as “CSI,” “Castle,” and “Magnum P.I.,” along with countless others that have told stories that sometimes take several episodes to develop fully, but give us a clear look at what the lives of their main characters are like every week. With the exception of it’s investigative reporter hero, “Les Vampires” doesn’t quite go that far, but one can definitely see how it points the way to an entire genre that people continues to enjoy today.

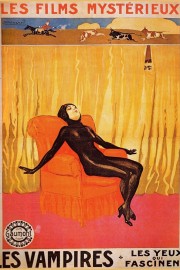

“Les Vampires” was an early discovery for me in my exploration through the silent era, and it’s remained a favorite of mine. The series is something of a police procedural, but, when it centers in on reporter Philippe Guérande (Édouard Mathé) and Oscar Mazamette (Marcel Lévesque), a reformed member of the Vampires- a secret society of criminals- one gets a hint of inspiration from Arthur Conan Doyle’s legendary sleuth, Sherlock Holmes. This is not to say that either Guérande or Mazamette are as brilliant as Holmes, but the dynamic between the two feels akin to that of Holmes and Watson, especially considering how the series ends. We do not focus solely on the heroes, however; as we are taken deeper into the world of the Vampires, several figures stand out, such as Satanas (Louis Leubas), the leader lurking in the shadows, and Venomous (Frédéric Moriss), a brilliant chemist who has some dangerous surprises for our heroes. None loom longer in the memory as Irma Vep (Musidora), the seductive thief, however; the image of her in the black, skin-tight cat burglar outfit is instantly iconic, and paved the way for characters like Catwoman in the decades to come.

From a visual standpoint, “Les Vampires” uses a predominantly straightforward approach to telling it’s story of a reporter trying to track down a gang of criminals, and is predominantly an example of “invisible style.” We get close-ups, tracking shots, wide shots, and sometimes crosscutting as a way of increasing tension. Feuillade uses many title cards to tell the story, which is important considering how often we see the characters talking. (We also see subtitles at times, when the characters are looking at printed words, but these could have been superimposed during the restoration of the series in 1996.) The most noticeable way Feuillade draws the audience into the film from a visual perspective that might have differed from his contemporaries is the use of a blue filter to signify scenes that take place at night, or in the dark (such as an early scene where a burglar sneaks into a woman’s room as she sleeps). The visual language of cinema had begun to solidify by the time Feuillade made “Les Vampires,” and he took advantage of the innovations up until that point to bring his epic crime saga to life.

“Les Vampires” lasting impact on cinema, and really, pop culture, lies not in it’s command of visual language (though it is an exemplary piece of visual storytelling), but in the story it tells, and how it structures that story. By splitting up his story into a series of episodes, he shows confidence not only in his audience’s ability to stay with the story across a long stretch of time (after all, while films of 2-3 hours (or longer) did exist in the silent era, they weren’t nearly as frequent as they are now), but also in the story, which includes a long sequence visually recounting a story a character is telling on-screen that has little to do with the narrative. The type of freedom for such a sequence the serial format gives Feuillade would not have existed in film structure of the time, although there were filmmakers (D.W. Griffith, for example, with “Intolerance”) who were trying to break the mold of traditional narrative, and adapt the literary model Feuillade emulates here to feature films.

Watching it in full for the third time in my life, I continue to be lured in by the thrilling “Les Vampires.” I’m also kind of surprised no one has done a straight remake of it, although I wonder if part of that has to do with the existence of Olivier Assayas’s “Irma Vep,” with Maggie Cheung playing herself as an actress during a disastrous attempt to remake “Les Vampires.” In the right hands, I think a filmmaker could capture the seductive pleasures of this series, and make it feel alive to an audience who might be scared to watch a 7-hour silent crime story. If you want to dive into the world of silent cinema, however, “Les Vampires” has always been an essential title for me.