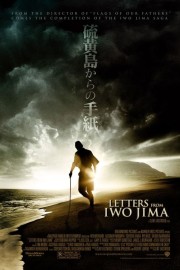

Letters From Iwo Jima

In more ways than one, “Letters From Iwo Jima” reminds you of the great Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. A look at the Battle of Iwo Jima from the Japanese perspective, it’s (sometimes unflinchingly violent) examination of individual honor and how it conflicts with honor to country is a theme that resonates through many of Kurosawa’s greatest films, notably his legendary samurai epics (“The Seven Samurai,” “Yojimbo,” “The Hidden Fortress,” and especially “Ran”) which provided the template for the past 50 years of American action films. But more than any of his recent films, “Iwo Jima”- perhaps as a by-product of its’ subject matter (and its’ approach to it)- made me see more clearly the similarities between Kurosawa and “Iwo Jima” director Clint Eastwood, whose study of mortality and morality in films as diverse as “Mystic River,” “A Perfect World,” and the Best Picture Oscar winners “Unforgiven” and “Million Dollar Baby” is comparable to the Japanese master. But more than just the underlying subjects of their films link the two; both are iconic filmmakers in their respective countries who have seen their artistic fortunes go from good to bad to good again over long careers (Kurosawa had to look to foreign investors to make his last five films; Eastwood’s artistry seemed to wane between “World” and “River”; both had late-career artistic resurgences, though Eastwood’s is more obvious than K’s), and both have found support from filmmakers inspired by their example to make some of their most personal films (George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg helped produce late Kurosawa works, while Spielberg has now produced three Eastwood films, including “Iwo Jima”). Who would have imagined such a comparison would be possible when American audiences first embraced Eastwood as an actor in those Sergio Leone Westerns?

“Letters From Iwo Jima” is the companion film to “Flags of Our Fathers”, which was released back in October to mixed- but mostly positive- reviews and disappointing box-office. By virtue of its’ subject- and the fact that, well, 60-plus years of World War II films from the American perspective have been seen, meaning cliches for the genre are well-worn- it’s a more conventional look at Iwo Jima as it was fought, which is part of the reason- in my positive review- I found myself a little less than enthralled by Eastwood’s battle scenes. I was much more intrigued by “Flags” main storyline- the PR tour three of the soldiers who raised the flag on Mount Suribachi in the iconic picture that inspired a memorial in Washington D.C. and a nation to support its’ troops fighting fascism- where the idea of heroism was twisted for the sake of fundraising, turning each public appearance into a personal struggle for the three survivors from the photo (played memorably by Adam Beach- robbed of a Supporting Actor nomination- Jesse Bradford, and Ryan Phillippe) who would rather be on the battlefield with their fellow soldier than glad-handing wealthy donors. Watching “Flags,” with the knowledge of “Letters” (originally slated for February, but wisely- and thankfully- pushed up for an Oscar run when “Flags” failed to draw them in) being right around the corner, I couldn’t imagine what Eastwood had in store with his look at the Japanese side of the battle.

It was nothing like what I could have expected. It’s a completely different film, taking place almost entirely on the battlefield (with little flashbacks to enrich character and deepen theme), and it’s riveting. The harsh reality of warfare that’s been so vital to modern war films since producer Steven Spielberg’s “Saving Private Ryan” is not backed away from in “Iwo Jima” (not that it was in “Flags,” mind you), and we’re fully engaged in it in Eastwood’s direction; how could the same director make two films about the same battle in the same year, where the audience’s engagement in the action is so distant in one (“Flags”) and so complete in the other (“Letters”)? Maybe because, while the battle on the ground wasn’t the focus in “Flags,” it’s the entire focus of “Letters.” Eastwood has done his subject proud, filming the thoughtful screenplay by first-timer Iris Yamashita (based on the story she wrote with “Flags” co-writer Paul Haggis) with the same uncompromising commitment to character and story we’ve come to expect from Eastwood in his best work, which “Letters” certainly deserves mention with, and in a way that illuminates the same ideas he examined in the very different “Flags” (in a way, it makes “Flags” a better film). And as always, his actors do their best for Eastwood. Ken Watanabe as Lt. General Tadamichi- a former envoy to the U.S. who is picked as the leader of the forces on Iwo Jima, and is an unwavering leader in the face of certain defeat (he refuses to give the order to commit suicide, though many are quick to turn to it- a painful sight- believing it a more honorable death than dying at the hands of the enemy)- embodies that struggle between personal dignity and duty to country with the same mournful nobility he brought to his Oscar-nominated work in “The Last Samurai.” And as Saigo, a regular soldier who’s taken away from his wife and his baby to serve his country, Japanese pop star Kazunari Ninomiya makes a lasting impression and plays a bigger role in the film’s arc than we might expect at the outset. They standout, but other characters will make impressions along the way; rare is the director who can make a war film that’s both memorable for its’ studies in character and its’ visceral action.

But Eastwood is a rare American director among those currently working in modern films, and with “Flags of Our Fathers” and “Letters From Iwo Jima,” he has made a rare accomplishment- two films that honor the soldiers (on both sides) on the battlefield who fought and died while criticizing the political establishments for their manipulation of their ideas of heroism. Both will be finding their way onto my DVD shelves, as they should yours, if only as an intriguing master class in direction in how to fully study a film’s subject from all sides, and do justice to both sides of the story.