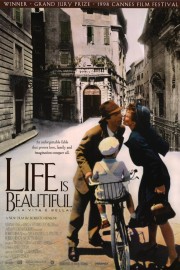

Life is Beautiful

Roberto Benigni’s Oscar-winning “Life is Beautiful” is really two films. Both of them are pretty great. The first half is a delightful romantic comedy, with Benigni’s Guido using his imagination and good humor to woo the woman that’ll become his wife (Dora, wonderfully played by Benigni’s real-life wife Nicoletta Braschi). In the second half, Guido must use those same skills to protect his son when he’s taken to a Nazi Death Camp in the last years of WWII.

The film received as much criticism as it did acclaim when it hit theatres in 1998 for the obvious reasons. Well, they aren’t that obvious to me. His harshest critics argued that Benigni, in the second half, was making light of the Holocaust. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Benigni is only illustrating one of the ways people try and protect themselves in the most dire of situations. Watching it again, you can see Guido’s desperation as clear as day as he tries to keep his hopes up, and keep up the spirits of his son Joshua. Five years after “Schindler’s List,” Benigni was finding his own way of dealing with an impossible subject. Like Spielberg’s masterpiece, the result is as uplifting as it is despairing.

It’s the most unlikely of masterpieces- as heartbreaking as it is reaffirming, as romantic as it is gut-wrenching, and as emotionally powerful as it is funny. The key is to realize something that should be obvious- this is a fable. The narration at the start of the film even says as much. That Benigni and co-writer Vincenzo Cerami would choose such a bold setting for such a story is one of its’ strongest qualities, as some things that were delightful are unsettling.

This is never more true than when Guido becomes friends with a fascist doctor. They share a love of riddles. Before the war, when Guido is a waiter working for his uncle, this is a delightful aside for both of them. But after Guido and his family are taken to the camps, and they meet again, all fun is taken out of the game. Guido wants to get out of the camp with his family, but the doctor’s affection for this uniquely delightful individual is gone…except for his need to figure out a new riddle.

Benigni’s talents are note-perfect. He has the comic abilities of Chaplin and the humanism of Spielberg. Both serve him well in this film. The first part of the film is a warm romantic comedy, with Guido and Dora seeming to run into one another (sometimes very literally) anywhere and everywhere, with Guido- after those first couple of chance meetings- going out of his way to be with her. It’s the type of classic romantic farce missing all too often in modern Hollywood artifice, as Guido impersonates a fascist school inspector, as well as her jerk of a boyfriend in a joyous scene where he uses overheard information to his advantage. Watching the film for the first time in eleven years, I didn’t realize how much modern romantic comedy was missing such lovely warmth and wit.

The first sign of the changing times comes when Guido’s uncle’s horse is painted green and with racial epitaphs on it. But Guido uses this tragedy to his advantage, as he rides to horse in to carry Dora away to their life together. We then see them five years later. He owns a bookstore, and they have a child. Guido hides the real nature of a sign that says “No Jews or dogs allowed” with his quick wit from his son, and that will be helpful when the two- along with his uncle (and Dora, a non-Jew, who asks to be sent to the camp with them)- are sent to the death camp.

It’s here where Benigni takes his boldest chances, and we are asked to make our biggest leaps of faith in the filmmaker. In reality, there’s no way Guido could get away with the elaborate bamboozlement he does in this film. He offers to translate for the German guards so that he can protect his son, even though he doesn’t know a lick of German. He uses an open microphone to let Dora know they are still alright, even though Joshua is the last child around after the others are sent to the showers. The lie is that the camp is a game, and the first to a thousand points will win a real tank.

It’s a preposterous rouse, but Benigni sells it beautifully. The reason is simple- this is who Guido is. We saw that in the first half of the film. He’s an optimist in a cruel and difficult world. It begins to take his toll (and it’s in these moments where Benigni deserved his Best Actor Oscar, which still rates as one of the most stunning upsets in Oscar history). Benigni’s truest responsibility as a filmmaker is to the character he created. That he chose to build such a bold and original story around him is his biggest accomplishment…well, until we see how beautiful the end result is.