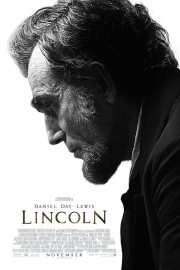

Lincoln

What Steven Spielberg does in “Lincoln” is rather bold, if you think about it. In telling the story of the passage of the 13th Amendment in January 1865, shortly before the end of the Civil War, the “Munich” and “Schindler’s List” director dramatizes the political process of backroom deals, and applying pressure on politicians to do the right thing on a moral level, even if it means political suicide. It makes one wish there were more, such individuals in Congress nowadays.

By design, Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner’s epic film lacks the emotional center of films like “Amistad” and “War Horse,” where the story is a personal one. I didn’t really pick up on that when I watched the film, but thinking about it after, it is the correct way of approaching this material. It also throws Spielberg out of his comfort zone, much in the same way their last collaboration, the criminally underrated “Munich,” did. Though there are deeply emotional moments in “Lincoln,” especially in scenes between Daniel Day-Lewis’s President, and Sally Field’s First Lady, Mary Todd, Spielberg’s focus is more procedural, as the 16th president tries, frantically, to hold off a possible peace to the fighting so that he can get this amendment passed.

Why would Lincoln– by many’s estimation, our greatest Commander in Chief –play politics with ending the bloodiest, and most tragic, war ever waged on American soil, even for an amendment as historically important as this one, which abolished slavery? His logic is sound: if it is passed BEFORE peace is negotiated, the Confederacy has no ability to oppose it, and they will be unable to stop it after they rejoin the Union. However, if peace is brokered before the Amendment is passed, ratified, and signed into law, the South can effectively kill it in the House of Representatives, where it has languished in the months since the Senate passed it. This chess match makes those closest to the President– such as Secretary of State William Seward (David Strathairn, superb); the abolitionist leader, Rep. Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones, in his finest performance in years); and Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook), a political ally who can deliver party support for the amendment, but is also concerned with the prospects of peace –worried about what might happen if either the amendment, or peace, fail. Though we know that both happened, there’s still a great amount of tension when Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy, sends a delegation up to discuss terms for peace, and Lincoln and his allies are racing to get the 2/3s majority necessary for passage of the amendment. What makes the urgency, and the drama of this particular moment, so potent is that this race is going on after Lincoln’s election to a second term, and before the new Congress convenes. There are 64 “lame duck” representatives who are going to be out of the job, and with only 20 votes needed to pass, Lincoln sees the potential for a deal with 1/3 of those as plausible. So funny how Spielberg, who insisted on a post-election release date to avoid politicization of the film, nonetheless finds the film as a perfect foil for our modern political climate as the race to avoid the “fiscal cliff” has lead to plenty of horse trading and an intriguing glimpse at tensions between the President and Congress boil over due to differing ideology, as well as the divide on social issues that effect millions, albeit in a less profound way on a moral level.

You will not hear any complaints out of me if Daniel Day-Lewis wins his third Oscar for his transformative performance as Lincoln. Yes, it lacks the remarkable energy of his last Oscar–winning performance, in 2007’s “There Will Be Blood,” but his Lincoln is equally-transfixing, albeit in a very different way. For the first time I’ve seen, it looks like Day-Lewis is having real fun playing a role, capturing an inviting, charismatic part of Lincoln’s personality we haven’t really seen before on-screen. He tells stories to make his points; he makes jokes to keep people at ease; he even takes time to listen to anyone whose opinions matter to him, whether its his wife; his political advisors; or even soldiers getting ready to head back to the front lines. This is not a larger-than-life historical figure, but a human being, struggling with important issues that will effect not only those in his lifetime, but in generations afterwards. Day-Lewis has a nice foil in Field’s Mary Todd, who is outspoken in public, but keeps Abe grounded when it comes to family life. Of course, even a legend like Field (herself a two-time Oscar winner) has a hard time matching the thundering commitment of Day-Lewis, but she helps center the heart of the film, which is always important in a Spielberg movie, even if it isn’t as up-front as it is normally in his films.

As I’ve written this review of “Lincoln,” which was based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, by Doris Kearns Goodwin, I find that my feelings on the movie have only strengthened. I still find it difficult to put the film on the same level as “Schindler’s List,” “Saving Private Ryan,” and other Spielberg masterpieces, but the director accomplishes so much, in yet another film that sheds light on our past as a way of, hopefully, inspiring us to make a better future. As he has always done, he uses strong actors (including, in this case, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jared Harris, and Jackie Earl Haley, all in small, vital roles) and committed behind-the-scenes artists (in particular, a long-time cinematographer, Janusz Kaminski, and composer, John Williams, who continue to do rich, emotional work for the filmmaker) to tell a story that may be very specific in the details, but is ultimately, a universal tale that anyone can relate to.