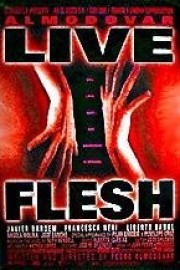

Live Flesh

One of the most unfortunate casualties of my limited theatrical moviegoing over the past few years has been my inability to keep up with Spain’s wild man, Pedro Almodóvar. Though I missed his acclaimed “All About My Mother,” his next three films- “Talk to Her,” “Bad Education” and especially “Volver”- produced some of my most memorable film watching experiences. Not always because I loved the films, but because of how singular they are. Comedy and drama, melodrama and suspense, emotional storytelling and surreal absurdity all seem to operate in the same space, sometimes in the same moment, and often shifting dangerously close to one another. It’s often said that no one makes films like “name of director here,” but with Almodóvar, that feels quite true.

The first film of his I watched was “Live Flesh,” and admittedly, it made it’s way into my collection (on VHS) for a particular moment of nakedness late in the film, but watching it in it’s entirety this morning, I appreciated it on the level of storytelling inventiveness that I have other Almodóvar films. Adapting a novel by Ruth Rendell, Almodóvar drives right into the lunacy of this situation and all it’s not-so-coincidences and comes out with a crazy piece of Spanish soap opera. The film begins in 1970, at a time when Spain is in a state of emergency. A young prostitute (Penelope Cruz) is pregnant, and she has to go to the hospital. There is no one on the streets, and her landlord stops a off-duty bus driver, wanting him to get her to a hospital. They don’t make it in time, and her son, whom she names Victor. Cut to twenty years later, and Victor (Liberto Rabal) is following the path of a petty criminal, and makes his way up to the apartment of a junkie, Elena (Francesca Neri), with whom he had sex with a week earlier. He wants to take her on a date, but she is not interested, and she is waiting for her drug dealer. Victor will not take no for an answer, though, and Elena pulls a gun on him, which goes off in a struggle. A neighbor calls the police, and Sancho (Jose Sancho) and David (Javier Bardem) are called to the scene. David prefers a by-the-book approach, while Sancho is more hot headed, not helped by his suspicions that his wife, Clara (Angela Molina), is cheating on him. Through circumstances when they arrive, David is shot and paralyzed, and Victor goes off to jail for six years. Meanwhile, David, who becomes a star player on the wheelchair basketball circuit, and Elena fall in love and get married. When Victor gets out, he goes to visit his mother’s grave, and sure enough, he sees Elena at a nearby funeral, and old feelings emerge.

A film like this would never work if one of the characters were not compelling, and it’s a great credit to Almodóvar that all five of the central players are fascinating, and more importantly, sympathetic. How else could we come to root for Victor if his upbringing, and the terms of his imprisonment, weren’t troublesome- after all, he is obsessed with another man’s wife? How could we not care about David and Elena if we didn’t appreciate the circumstances which brought them together, and the affection that led a junkie to care for this good cop who got a bad hand dealt him that fateful night? Clara and Sancho are the tough characters to sympathize with- after all, Clara is cheating on Sancho, and Sancho is emotionally and physically abusive towards her. But there’s a pain that connects those characters that is palpable and powerful, making it fitting that the climax of the film will center on them, as it is ultimately their troubled relationship that set everything in motion. Victor is the protagonist of the film, and the triangle he finds himself in with Elena and David is the heart of the film, but it’s Clara and Sancho whose choices will lead to a complicated resolution for all involved. Almodóvar loves these characters, and has cast actors who convey his sympathetic view of them. As always, though, he holds a particular compassion for the women in the film, starting with Cruz’s prostitute in the prologue, and continuing as we see Clara and Elena move through the events of the film. He may have a reputation as a “wild man” of Spanish cinema, and his films can get pretty wild, but the way he respects his female characters is always unforgettable and profound, even if the world around them is kind of crazy. That conflict is part of the reason why Almodóvar is a name to be revered in world cinema, and though not among his best work (“Live Flesh” feels like a minor key film for him), this is a good primer for people who have never seen a film of his before. One look at “Live Flesh,” and I think you’ll be back for more. I know I was.