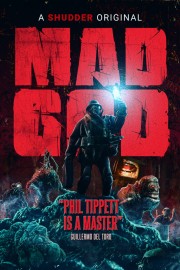

Mad God

Phil Tippett is one of the fathers of modern visual effects. He has his name on some of the most groundbreaking films of all-time. But once CGI films began to evolve, stop-motion animation- a tried and true artform responsible for King Kong and Medusa- seemed on its way out the door. So, Tippett took an idea he had for a story, and over 30 years, crafted “Mad God.” The story, largely told without dialogue, is a dark fantasy about exploring a nightmare world and creation, but the narrative pales to the world Tippett and his fellow animators have created. This is an ambitious and visionary work of art.

We follow a man in what looks like he’s headed into a toxic environment, like a coal mine or a radioactive wasteland, as he enters a land that does, in fact, look like a post-apocalyptic wasteland. It isn’t uninhabitable, however; there are creatures and beings of all forms. The man is there to destroy this world, but before he can, he is captured, and displayed for onlookers. That sets into motion events that challenge our perception of the world in this film, and whether sometimes, death is a way to get to life.

The narrative in Tippett’s screenplay gets lost in the images, but this might be one of those rare cases where that is not a bad thing at all. Seeing as the film essentially works as a silent film, “Mad God” exists for those images. The story is tenuously held together, at least enough to where you are given something to follow along with, but what matters to Tippett is the act of creating motion, one movement at a time. This looks like a film that took three decades to wrestle on to the screen, every time a character or background shifts an act of herculean strength. I can’t help but think of the old nightmares of the silent era- your “Cabinet of Dr. Caligaris” and “Haxans”- while watching “Mad God,” but part of what makes the film such a remarkable, imaginative experience is how this film, which sometimes seems to wallow in the macabre, feels oddly hopeful by the end. The events that lead to that hope don’t make sense, but as the God who created this world, it’s not Tippett’s responsibility to reveal all to us; we’re to figure out the reasons for ourselves.

There are images I will never forget from this film- the alchemist who takes an unnerving-looking child to experiment on. Our “hero” being tortured for the amusement of this place’s citizens. The hero’s eyeball, hopelessly looking on at his fate. Fights that bring to mind the great stop-motion sequences of yor. And the creation of life itself in the muck. With a haunting score by Dan Wool, Phil Tippett reminds us of the simple pleasures of an art form as only the great creators in movie history do.