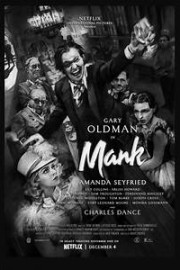

Mank

I reckon it would be easy for someone to make a movie about making “Citizen Kane.” Obviously, any movie getting made is a Herculean task, but in terms of coming up with the idea of doing a movie about the making of, and release of, “Citizen Kane,” it doesn’t take a lot of thought. Few movies are more written about, few births have been as well-documented, and few stories are as infamous as when Orson Welles, in his first film, where he was given absolute reign over his project, took on the life of William Randolph Hearst. All you have to do is watch the documentary, “The Battle Over Citizen Kane,” to give you almost anything you would need. For his first feature in six years, David Fincher gives us 132 minutes about the writing of “Citizen Kane,” and the result is probably his most entertaining film since “Fight Club.” Not his best, mind you, but none of his other films in the 21-year span between “Fight Club” and this have put a smile on my face quite like this one does.

“Mank” is not a film that can simply exist on its own- some familiarity with “Citizen Kane,” and its creation, will no doubt help- but I don’t know if you absolutely need to rewatch “Kane” prior to seeing it to enjoy it. A lesser filmmaker would make a film that nudges and winks at “Kane” at every turn while telling the story of how Herman Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) holed up in an isolated home, recovering from a car wreck, and wrote the first draft of the film known as “The American,” the original title “Kane” went under. One of the things I love about Fincher’s film is how, while he shoots in black-and-white and dives deep into the cinematic language of the era, we don’t get a whole lot of outward visual references to Welles’s film along the way. That actually makes sense- “Citizen Kane” was the most groundbreaking technical achievement, and rewriting of film language, since “Birth of a Nation,” and since our story takes place prior to it being made, an emphasis on deep focus and the other types of camera angles and visual tricks Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland brought to the film would have not only been too obvious, but not quite in keeping with the era. This is old school Hollywood, and Fincher is relishing in telling a story in this era.

The screenplay for “Mank” is by Jack Fincher, David’s father. Jack Fincher passed away in 2003, and though he was a writer in his own right, this was his only screenplay. David initially wanted to make it after “The Game,” but couldn’t get it off the ground. The script is inspired by a claim in Pauline Kael’s famous New Yorker article, Raising Kane, which was that Welles did not deserve screenwriting credit alongside of Mankiewicz for “Kane,” a claim which angered many critics, along with filmmaker and friend of Welles’s, Peter Bogdanovich, who refuted Kael point-for-point, and eventually, her argument was discredited entirely. The battle over “Citizen Kane” continued. Does that make “Mank” a whole lot of hooey? Not necessarily; even though they share screenwriting credit, and shared the film’s only Oscar win, Mankiewicz is often marginalized in discussing the film, even though he was the one who had the basic idea for the story. Telling his story is well worth anyone’s time.

The film does take on one thing of “Kane’s” in its telling of Mankiewicz’s story, and that is moving back and forth in time. The main crux of the action takes place in the bungalow where Mankiewicz is recovering, and writing out the story for “The American,” with a typist and caregiver (Rita Alexander, played by Lily Collins) helping try to keep on schedule- he has 60 days to get his first draft to Welles, played by Tom Burke. Mank has a long history with alcoholism, and his handlers want to keep him off the sauce as much as possible, but he certainly has people around him willing to enable him in that. Along the way, we move to different points in the early 1930s, seeing Mank on the lots of Paramount and MGM, seeing him navigate a Hollywood where writers were basically treated as court jesters, or monkeys at typewriters, for the power brokers like Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard), David O. Selznick (Toby Leonard Moore) or a media baron like Hearst (played by the excellent Charles Dance). Mank became part of Hearst’s circle at San Simeon, in part because of his friendship to Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), an actress who had previously been linked to Charlie Chaplain, and was now a close acquaintance of Hearst’s. In these flashbacks, we see the seeds of what would become “Citizen Kane” be laid in front of Mankiewicz, as well as the political shifts in the industry that would make the collision of Welles and Mank and Hearst such a volatile one.

Fincher having to wait over two decades to make “Mank” makes a lot more sense, given the trajectory of his career. Though he’s had difficulties within the studio system from the outset with “Alien 3,” the now 58-year-old Fincher has the war wounds of going up against the establishment for his projects that Mank had by the time he was in that bungalow, ready to attack the status quo, and Hearst, head-on with “Citizen Kane.” Not just because his father wrote the screenplay (which was polished by an uncredited Eric Roth), this feels like Fincher’s most personal film about his experiences in dealing with studio heads and a world where filmmakers are often seen as court jesters, or simple contract workers, rather than artists. The film being made for Netflix rather than one of the traditional majors makes sense, because, at the time, RKO (the studio that released “Kane”), was on the outer rim of the major studios, as well, and thus, were not afraid of taken big swings on visionaries; after all, they gave Welles, a man who had never made a film before, cart blanche to do whatever he wanted. In Mankiewicz, Welles found the ideal foil- someone who was on the inside, who was ready to lob hand grenades at the power structure of the industry.

As with “Citizen Kane,” it’s easy to see why “Mank’s” technical accomplishments have kind of overshadowed its emotional pull with critics. The cinematography by Erik Messerschmidt is extraordinary, as he and Fincher really lean into the “old Hollywood” aesthetic of the time, and the way they use the widescreen is masterful in the same way deep focus helped define “Kane.” The production design and costumes are all spot-on, and the editing by Kirk Baxter keeps us in balance even when the timeline is moving back-and-forth. The music by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, now collaborating with Fincher for the fourth time, is a beautiful evocation of the sound of old Hollywood from the musical visionaries, who continue to place their stamp on the world of film music. And the performances are all on point, with Dance, Seyfried and Oldman all getting at the heart of their characters, even if only Oldman is the one we are emotionally connected to. That’s the only one that matters, though; after all, “Mank” is his story, and the story of any artist who has ever looked at the world they move around in, and was ready to challenge it in a way where nothing was ever the same afterwards. No, “Mank” isn’t as revolutionary as “Citizen Kane” was, but that spirit is impossible not to feel as we watch it.