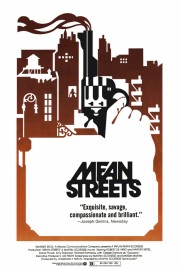

Mean Streets

When your first big breakout film involves life on the edge of crime, and then have “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull” immediately hailed as masterpieces after that, it’s understandable that your filmography gets boiled down to a particular type of film. It’s not necessarily correct, but it’s understandable. Martin Scorsese is always hunting bigger spiritual and moral game, however, than just doing a cops and robbers movie, however; that’s what really becomes clear the more you delve into Marty’s films beyond the “GoodFellas,” “Casinos” and “The Departed.”

“Mean Street” might be the most personal of Scorsese’s crime films, although the best ones do have personal stamps from the director on them. It’s not based on a true story like “GoodFellas” or “Casino” or a genre remake like “The Departed,” but what it has is the young (at the time) director developing his personal style with camera and editing while showing his main character, Charlie (played by Harvey Keitel), going through a dilemma when it comes to allegiances on the streets as his best friend, Johnny Boy (played by Robert DeNiro in the performance that heralded his arrival), puts him in contentious positions with people around him. That’s something I didn’t necessarily pick up on about 20+ years ago when I watched it; it rings true now.

The first images we see of Charlie is in church. He is praying, and we hear over the images voiceover where he has been told that Hell feels like flames across your hand. He holds his hand over candles to feel it. He feels as though he is in a state of sin every day of his life. On the streets, and in the bars, he is in a life of crime where his father is one of many loan sharks and low-level criminals, selling items they buy off the backs of trucks, every day. The most significant of these is a loan shark named Michael (Richard Romanus), who hounds Charlie over the debt Johnny Boy, a gambler who owes money to everyone, has accrued. That, on top of the secret relationship he’s having with Johnny Boy’s sister, Teresa (Amy Robinson), are the biggest issues going on in his life- we’ll see if he can juggle them all.

With the exception of the Roger Corman-produced “Boxcar Bertha,” I have not seen any of Scorsese’s early work, but “Mean Streets” feels fully formed as an experience of Scorsese’s talents. The camerawork by Kent L. Wakeford has a lot of the tracking shots and quick pans Marty and his cinematographers would become known for, and the editing by Sidney Levin has an energy and tension that ebbs and flows the deeper Charlie and Johnny Boy are in the whole with Michael. The soundtrack is a great indicator of the sort of musical curation Scorsese would do for his best films, when he opted for both source music and mood songs for his films. What sets this apart from Marty’s other crime films, even the ones I would say are better, is the way he and co-writer Mardik Martin put the toxic friendship between Charlie and Johnny Boy at the center. Charlie has a soft spot that is a blind spot in the way he reacts to Michael and others. He’s willing to take a lot of shit for his friend, even if he doesn’t deserve it. That might bite him in the end, though; with Scorsese, even the best intentions have a likelihood of getting punished, especially with a wild card like Johnny Boy involved. That rings true all these years later in the film that really put Marty on the map.