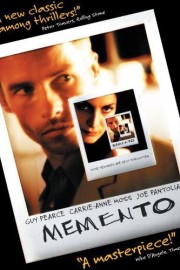

Memento

With “Memento,” Christopher Nolan would show us the filmmaker he became in later films: personal, challenging, and riveting. In other films, such as “The Dark Knight,” “Inception,” and “The Prestige,” he would have bigger budgets, and more technically demanding stories, but his second film set up the thematic motifs he would explore in every film before (his 1998 debut, “Following”) and after. He has never strayed from the notions of psychological damage he and his brother Jonathan (who wrote the short story “Memento” is based on) study here.

The film, as I’m sure most know by now, is about Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce), a widowed husband who suffered a loss of his ability to make new memories in the attack that killed his wife. Since the accident, he has been hunting for the killer, and with the help of Natalie (Carrie-Anne Moss) and Teddy (Joe Pantoliano), he is getting closer than ever. Both characters hold vital clues not only to Leonard’s future, but also his past. But can Leonard trust either one of them? He can write things down on Polaroid photographs, and get tattoos to remind him of the really important things, but if he’s meeting everyone he encounters as if it were the first time, how can he function in this world?

Part of what made “Memento” such a stunning achievement when it came out in the US in January of 2001 was Nolan’s decision to tell the story in a non-linear form. Most critics, myself included, said that he had told the story backwards, and in a way, that holds true, but what he really does, and what became obvious when we were able to see the film in chronological order on DVD, is has the beginning and end meet in the middle (more or less). I’ve seen the film a couple of times in chronological order, and it holds up pretty well, but the tension is ratcheted up as we see Leonard talking to someone on the phone in a motel room, while also seeing the events leading back from Teddy’s death (at Leonard’s hands) to a key moment when Leonard burns a photo he’s just taken. It’s an editing trick that, skillfully, allows us to enter Leonard’s mindset, as we experience the story unfold a few minutes at a time, unsure of what we’re going to find out next.

One of the things that stood out most watching the film this time, however, was the way Nolan develops the characters of Natalie and Teddy throughout the film. Leonard is, fundamentally, a one-dimensional character; like The Joker in Nolan’s “The Dark Knight,” Leonard is an absolute, unyielding individual that sets the story in motion, forcing the characters to react to his in their own ways. But Natalie and Teddy evolve in interesting ways. At the start, we think Teddy has been playing Leonard, and that’s part of what leads Leonard to shoot him, but as the film moves back in time, we see that he, in fact, is looking out for Leonard, and trying to help him move past the memories he cannot remember, even if it leads to awful things being done, and his own demise. Natalie is just the opposite, in fact. She starts as someone who seems to genuinely care about Leonard, but as we see the story move to that point in time, we see that she is also driven by anger over losing a loved one, and she uses Leonard for her own gain. All three actors are superb in their respective roles, although Pearce does deserve special recognition for the heartbreaking intensity and pain in Leonard, a man looking for peace, but unlikely to ever achieve it for reasons he cannot control.

A decade-plus after its release, “Memento” remains one of Nolan’s best films, if not his best. (I vote for “The Dark Knight” personally.) With fewer resources, and unwavering resolve, Nolan tells us a story of a damaged individual who does terrible things in pursuit of inner peace, much in the same way his Bruce Wayne does in the “Dark Knight” trilogy; or Al Pacino’s detective in his next film, “Insomnia”; or Hugh Jackman’s driven magician in “The Prestige” (Nolan’s most underrated film, as well as my personal favorite). Only Dom, the dream thief Leonardo DiCaprio plays in “Inception,” seems to mirror Leonard’s true nature, that of an individual who has had to make tough choices after tragedy, but is ultimately a good person, and not a closeted sociopath. But even Nolan is capable of finding humanity in those other characters, displaying a sense of humanistic purpose that has gotten lost in his typically-serious films, but is rival to the warmth other masters (Joss Whedon and Steven Spielberg come to mind, in particular) get more credit for.