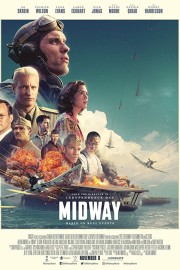

Midway

It’s kind of amusing that I just finished writing a piece for a different website wherein I talk about a “male gaze” when it comes to military films, and one of the next films I watch both confirms that feeling, while also sidestepping a lot of things that make war and military films a dime a dozen. To his credit, director Roland Emmerich actually does something unique in terms of American-distributed war films with “Midway,” even as there are some cliches he really cannot escape because of the type of filmmaker he is, at his core. What is “unique” about “Midway” is what makes it interesting to watch.

One of the things I did not expect was how “Midway,” and its screenplay by Wes Tooke, would build up to the Battle of Midway in 1942. We begin in 1937, before war has gotten underway, as Edwin Layton (Patrick Wilson), a US intelligence officer for the Navy, is in Japan for a summit, and the discussion is one of (hopefully) keeping the peace in the years to come. Cut to the morning of December 7, 1941, and the attack on Pearl Harbor. Layton is one of the officers whose concerns about a potential Japanese attack went unheeded, and we also meet Naval pilots aboard the USS Enterprise, as well as people in Pearl Harbor at the time of the attack. We actually see a great deal more of that attack than I expected, but it is prologue to a back-and-forth few months between the American and Japanese fleets leading up to the critical Battle of Midway, where Layton assures the new commanding officer of the Pacific fleet, Chester W. Nimitz (Woody Harrelson), the next major step in Japan’s plan to control the Pacific will take place. We also come to meet Dick Best (Ed Skrein) and Wade McClusky (Luke Evans), and other pilots on the Enterprise, as they prepare to get vengeance on the Japanese Navy, and hopefully, catch them by surprise, as well. I felt like this film approached its subject like a procedural or documentary, hitting the main historical points along the way to the big battle scenes at the end, and while I admire that approach, it also dragged the film down in plot and exposition. It was a welcome change of pace.

Something that was another change of pace for the war genre, especially one with a dominant American point-of-view, is how the film approached both the American and Japanese side of the conflict. Asian co-financing no doubt was a part of that, but this is still a pleasant reprieve from how most war films have the other side as an almost faceless collection of targets for the “good guys” to get. We see how things unfold on both sides of the conflict, even if it ends up being weighted to the American perspective, and we see how the leaders on both sides are certain in the way they are conducting things. The story being told, and how it’s told, can only do so much to cover up performances that are solid at best (especially from Harrelson and Wilson) and mediocre and forgettable at worst (Skrein as the lead especially falls flat), and the fact that, when the bombs begin to drop, a filmmaker like Emmerich cannot abandon his base instincts as an entertainer to bring dramatic weight to the horrors of war. Michael Bay had the same problem in “Pearl Harbor” almost two decades ago. At least Emmerich’s film doesn’t feel the need to graft an artificial, and uninspired, love story to a narrative that is compelling enough as it is.