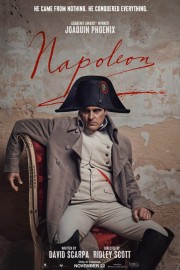

Napoleon

Even the best intentions can be undone by gaining political power. From the outset, however, it’s clear Napoleon Bonaparte did not have the best intentions; instead, he just saw himself as someone destined to be a leader in France after the revolution. One of the unique qualities of Ridley Scott’s historical drama is that, while Napoleon is at the center of the action, at no point do we see him as a heroic character. He is driven by ego, and insecurities, until the end of his life.

It would be easy to view Napoleon in the context of former President Trump, a leader consumed by the desire for power, and holding onto it, that he contested a democratic election to the point of revolution on January 6, 2021. But Trump is only the latest of a history of political leaders whom wrap themselves in the flag of nationalism and populism as a means to put themselves in a position to demand loyalty of the population which put them there. Like Napoleon, however, Trump tries to project strength, but all many of us see is the insecurity that comes from someone entitled to power. In Scott’s film, where Napoleon feels the most exposed is with Josephine, the common woman he takes as his wife, and whom will haunt him for the rest of his life, even after he has remarried, all in hopes of gaining an heir that Josephine could not give him.

Ridley Scott is a filmmaker of significant vision whenever he steps up to the plate- whether it’s “Alien” or “Blade Runner” or “Gladiator” or “American Gangster” or “Black Hawk Down”- whose best films come from the moments when his visual style are matched with a strong script. “Napoleon” is an interesting case study for fans of the director. Written by David Scarpa (whose last script for Scott was 2017’s “All the Money in the World”), “Napoleon” feels like it follows the facile biopic template of historical epics past, giving in to being a “greatest hits” of the character’s major moments during the time Scott’s film takes place. Having said that, I think Scott’s own hubris and vision elevate the film beyond being a stale biopic. A big part of that is the casting of Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon. This is his first collaboration with Scott since his Oscar-nominated work in “Gladiator,” and Phoenix’s Napoleon and Commodus are very much cut from the same cloth- they betray allies if it benefits them, and their self-image is rattled by the popularity of others. The big change is the absurd sense of humor Phoenix brings to the role. Napoleon’s insecurity is wide open for the world to see, and Phoenix isn’t afraid to have fun at Bonapart’s expense. It is a delightful performance from the actor.

On the other side of the equation, we get Vanessa Kirby as Josephine. Her husband was killed in battle, and they meet when Napoleon brings her husband’s sword to their son, who wanted to keep it. From there, Napoleon is struck by her beauty, and insists on having her as his wife. One can see that it is a one-sided love from the start, but we don’t get a feeling that Josephine is in it simply for power. She does recognize her power over Napoleon, though, and isn’t afraid to use it. Kirby has some great moments in the film but her character does feel underdeveloped compared to Napoleon, to where- when she is sidelined from the drama- it isn’t as big of a loss to the film as it feels like it should be. It’s hard to tell if this is Scott’s failing or the script’s, but it’s not Kirby’s fault; she shines when she’s allowed to.

One thing Scott is in complete control of when it comes to “Napoleon” is the spectacle. The way he films the end of the revolution- and Marie Antoinette’s demise- is the first example of his brute strength as a director when giving us a front seat to the violence. Napoleon is shown to be a ruthless commander on the field of battle almost as much as his ego gets away from him, as it does during an ill-advised Russian invasion, and the Battle of Waterloo. I was captivated by the visual landscape Scott and cinematographer Dariusz Wolski create in this film, and how 19th Century France is brought to life with detail and vibrancy. As a visual experience, “Napoleon” delivered, and those visuals- for me, at least- helped illuminate the ideas in how Scott approaches Bonapart’s life in this film. Like most Scott films, however, your mileage may vary with how much you are engaged with the main characters. I was, but it’s not hard to see others having a tough time doing so.