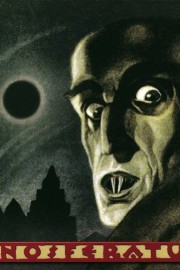

Nosferatu

**I also wrote about “Nosferatu,” and how it is thematically different than other Dracula adaptations at In Their Own League.

The most difficult decision in finally reviewing F.W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu” is what score to listen to with it. The silent masterpiece, the greatest adaptation of Bram Stoker’s story in film history, has had several composers and musicians contribute to its legacy of terror. Renowned Hammer Film composer James Bernard composed a score once, which is a superb listen in and of itself, while the DVD I own has two compelling scores: one an organ work by Timothy Howard that I used to favor, and the other by the Silent Orchestra which is more eclectic and modern. I decided to go with the Silent Orchestra’s score.

Regardless of musical accompaniment, however, “Nosferatu’s” power lies in the images it captures. Silent film was never better than it was in the telling of horror tales or comic fables. And few of either genre match the artistry of “Nosferatu.”

Even with the names changed, the similarities with Stoker’s “Dracula” are obvious. So obvious, in fact, that Stoker’s widow brought suit against the German studio that failed to license it for adaptation. She won the legal battles, but in the end (almost as mysteriously as the movements of Count Orlok himself), Murnau and the film won the war. Though many prints were destroyed, the film eventually resurfaced in London, and later America (where the copyright of the book had expired), and the rest, as they say, is history. Even a little bit of revisionist history, when “Shadow of the Vampire” opened in 2000 and proposed what may have been had Max Schreck (who played the vile Orlok) been a vampire himself. So haunting is Schreck’s performance that you kind of believe it.

This is the greatest vampire story of all-time. Superior to the Todd Browning and Bela Lugosi work at Universal (iconic as it is). Superior to the Hammer films with Christopher Lee (though the first one, “Horror of Dracula,” is a masterpiece in itself own right). And superior to Francis Ford Coppola’s epic retelling in 1992. Werner Herzog’s own remake of Murnau comes close, as does 2008’s haunting “Let the Right One In,” but nothing exerts this film’s hold on the viewer when Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) is sent to Orlok’s castle by his creepy boss Knock (Alexander Granach) to sell him the property across from Hutter’s house. If you know “Dracula,” you’ll know the story beats, even if you don’t recognize the names.

It’s the lack of a soundtrack that makes this a masterpiece. No dialogue to snicker at. No sound effects to telegraph terrors around the corner. Just the natural discoveries that come as scene-from-scene, shot-from-shot, change on their own stopwatch. And what visuals those shots and scenes capture! The cinematography and art direction aren’t elegant but ugly. The pictures don’t move with the sweep of a stylized epic (as they do in latter versions) but seem to capture moments that might be best left uncaptured by a camera. Even heroic moments by Hutter and the villagers as they try to capture Orlok feel less heroic and more hopeless against the feelings of dread within Murnau’s film. And a scene on the beach, scored by the Silent Orchestra with lovely romanticism, is undercut by the tombstones we see on the sand hills.

Films like “Nosferatu” cannot be made right now. The last time filmmaker’s to create such unnerving images were in the silent era. Even the latter masterpieces of the genre are lacking this film’s ability to send shivers down a viewer’s spine. I’d love to see such films again, and filmmakers like Herzog and Matt Reeves, who directed this year’s “Let Me In,” certainly have the artistic talent to accomplish such things. But the cinematic landscape has changed, and such expressionistic images are frowned upon. Well, by the moneymen at least. If the enthusiasm of pockets of viewers for films like “Let the Right One In” had their way, maybe we’d be able to recapture that old dark magic.