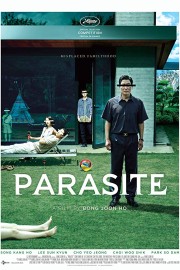

Parasite

I have a terrible feeling that, as with Chan Wook-Park’s “Oldboy,” someone is going to get the idea to remake Bong Joon Ho’s jet black thriller, “Parasite,” for an American audience. This premise is just too good to pass up. The problem is that whomever does so will fail because they will likely lack the visual acuity and satirical voice to pull it off; plus, there’s something about the setting that is just too perfect. We need to be transported to another culture for this, because it’s just too crazy to think it can happen here.

“Parasite” is a singular experience, from a filmmaker whose work is filled with singular experiences, and I’m anxiously excited to really dive into it further. “The Host,” “Snowpiercer” and “Okja” are all films from a director whose storytelling is clear-eyed, and unique in the way he approaches themes and ideas. “Parasite,” which he co-wrote with Han Jin Won, might be his most intimate work to date that I’ve seen, but it covers ideas that are bold and universal in a way that we’ve never really seen before.

The film begins with Kim Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho) and his family in their rundown apartment in the slums. None of them have jobs, save for (occasionally) folding boxes for a neighborhood pizza place. Their apartment is below street level, and with no money, they don’t can’t afford wi-fi, so they take from what network is available to them, even if that means finding that sweet spot in the bathroom that is free. One day, a family friend drops in with a rock for them that Kim’s son, Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik), says is so “metaphorical,” although we wonder if he even knows what that means. The friend is actually getting ready to go abroad, and he thinks he can get Ki-woo a job tutoring a rich family’s daughter- he trusts Ki-woo with her over some college guy who is going to just try and seduce her, because he wants her for herself when he gets back; to him, Ki-woo is not threatening. Ki-woo does, in fact, get the job, but he also sees opportunities for his father, mother (Jang Hye-jin) and sister (Park So-dam) for employment. For them, this is a chance for them to get back on their feet, as well as get a taste of a life they only dream of from the second he steps into the Park’s remarkable home.

To a certain extent, I hate even revealing that much of the story, because one of the genuine pleasures is seeing how the family sees opportunity on top of opportunity to ingratiate itself into a lifestyle they cannot experience for themselves. Based on the cursory description right there, you’ll no doubt believe you have an idea of how the title fits in to the story, and while you are technically correct, there’s more to Bong’s story than we think, and the big idea he is working from. Let’s look at the Park family, which is the rich family whose daughter Ki-woo goes to work for. While they appear to function as a family unit, their ability to function as individuals relies on the assistance of others. The father (Lee Sun-kyun) is someone who takes advantage of his wealth to having a personal driver take him to and from work, and his wife (Jung Ji-so) out for errands- he has that privilege. But he also has a philosophy about “crossing the line,” something he notices Kim just on the edge of without entirely doing (except his smell, evidently, a comment that plays a part narratively, and thematically, as the film continues). In this film, that idea of “crossing the line” is introduced with Min, the friend- never seen again- who vouches first Ki-woo originally. It’s essentially about staying in your lane that society has put you in, something the Kims do not do, but Min is not as interested in it, either- think of the reason he thought of Ki-woo in the first place? The Park’s stay in their lane, but from what we see in the film, it’s one where they take advantage of help to keep from getting themselves too involved in life. They hire people to help their children, even though the wife does not seem to have a job, and they have a housekeeper to cook and clean; say what you will about the Kims, they are not just looking to mooch, and have a strong bond as a family. This isn’t as simple as a haves and have-nots social commentary, though; it’s about how everyone has a line they will cross if it benefits them to do so, even if it’s with the best intentions.

This film would be worth watching for the narrative Bong is weaving, but my God does this film look and sound amazing. The detail he has put in to the Park’s house, this utopia the Kims are stepping in to, is as important as any plot point in “Parasite,” and production designer Lee Ha-jun’s work is as precise and exacting, and important to the story of the film, as any of the great locations in cinema, whether it’s the Overlook Hotel in “The Shining,” Rick’s Cafe in “Casablanca,” Xanadu in “Citizen Kane” or the Bates Hotel in “Psycho.” There are important clues sometimes right out front that we do not pinpoint as clues until the right moment, and cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo’s lighting and camera movements from the first time Ki-woo enters the house leave us transfixed. The sound design in the film is vital to how we experience the world Bong creates in “Parasite,” and the musical score by Jung Jaeil sounds like classical elevator music, but it gives each scene a personality and feel that puts us into the emotional landscape of the story in a new way.

About halfway into the film, the Parks leave for a family camping trip to celebrate their son, Da Song’s (Hyun-jun Jung), birthday, and the Kim family crosses a line, taking the chance to run rampant in the house. But every home has its secrets, and there is a reason that they celebrate Da Song’s birthday out of the house. The secrets in this film are unexpected and only add layers of depth to the story Bong has put together, where nothing is what it seems, and the title has different meanings depending on whom you’re talking about.