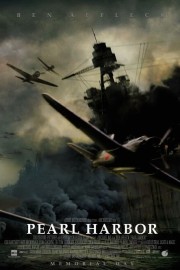

Pearl Harbor

Watching Michael Bay’s “Pearl Harbor” for the first time since 2001 this week, I didn’t even get to the half-hour mark in this film before it occured to me what the biggest problem the film has: while Randall Wallace’s screenplay deals with the lead up to and aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Wallace and Bay seem more interested in the love triangle between Ben Affleck, Kate Beckinsale, and Josh Hartnett. More compelling would have been to follow Affleck and Hartnett’s pilots as they move up the ranks, and allow the love story to grow naturally from the situation. Instead, the film follows the “Titanic” approach and starts with the love story, and using the attack as a setting. It works in “Titanic” because James Cameron was even more passionate about the story of Titanic’s one and only voyage than he was his lovers. Here, you wonder whether Bay, Wallace, and producer Jerry Bruckheimer even care about the context and real significance of how (and why) Pearl Harbor was important to history.

It’s not the fault of the actors that “Pearl Harbor” fails as drama and history: Affleck, Hartnett, and Beckinsale all give it their level best to make us care about these characters, but they lack depth and singular personalities. (Say what you will about “Titanic’s” Jack and Rose, Cameron made those two unique individuals.) The bond that resonates strongest in the film is between Affleck’s Rafe MacCawley and Hartnett’s Danny Walker. Childhood friends, Rafe and Danny have been joined at the hip ever since Danny’s father (William Fitchner), drunken and shell-shocked after fighting in WWI, physically attacked them when they were children. Rafe was always the strong one, and the one who takes chances, which is why he volunteers to fight with the Royal Air Force even as the US remains out of the war. Unfortunately, Rafe is leaving behind a great girl, Beckinsale’s Naval nurse Evelyn, but the two remain in constant communication. On a raid, however, Rafe is shot down, leaving behind a best friend and a distraught girlfriend. I’m sure you can figure out what happens from there.

What holds my attention about the film, however, is the depictions of Japanese preparations for the sneak attack, and the government’s attempts to stay a step ahead as it appears the Japanese are up to something. Instead, Bay and Wallace insist on cutting away to picturesque images of young lovers set to Hans Zimmer’s swooning adaptation of his theme from “The Thin Red Line,” which he uses (rather uninspiringly) as the love theme for this film. It’s unfortunate that the most devestating attack on American soil before September 11 (which occured mere months after this film’s release, and dated it immediately) apparently wasn’t dramatic enough to make a movie out of.

All that being said, “Pearl Harbor” is far from Bay’s worst film; his previous film, 1998’s “Armageddon,” holds that honor almost definitively. Yes, his focus is less on the historical event and more on a bland love story, but when the Japanese attack on December 7, Bay and his technicians are on top of their game. No matter how you feel about his films, there’s no question that Bay can shoot an action sequence, and his staging of December 7 is one of his best accomplishments, held back only by Disney’s insistence on a PG-13 rating. It’s the first time I feel some genuine emotion for what’s happening on-screen. Bay is channeling Spielberg’s direction of warfare in “Saving Private Ryan” in this sequence, and you feel the tragedy of combat. Well, I did, and I know that’s the unpopular opinion when it comes to “Pearl Harbor,” but what can I say? As much as I hate when Bay gives into his basest filmmaking instincts (and there are moments in this film that rival the silliness and crass manipulation of Bay’s worst films, “Armageddon,” “Bad Boys II,” and “Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen”), the 30 minutes-plus devoted to the “date that will live in infamy” isn’t one such moment.

Still, that’s 1/6th of the film’s 183 minutes that’s a genuine success in the way the filmmaker’s hoped. The rest of the film is a mismash of interesting history fighting with a simplistic love triangle. There are a lot of good actors in a lot of different types of roles here, from Cuba Gooding Jr. to Jon Voight (as FDR) to Alec Baldwin and Tom Sizemore and Jennifer Gardner, and all of them do what they can to take this film seriously, and respectfully; they succeed as much as one can with Wallace’s screenplay. The cinematography by John Schwartzman is very good at times, but other times is shot with a gauzy style that is annoying to watch. And even though I criticized Zimmer’s score earlier for its blatant rehashing of material, the Oscar winner, like Bay, can still make action resonate with the best of them. I honestly expected to rip this film a new one as I did with “Armageddon” in watching it again, but I’m actually finding that my opinion now remains similar to the one I held ten years ago: some good, some bad, a little great, a lot groan-worthy. That’s a lot of different things going on in a three hour film, but for a Michael Bay film, well, it’s pretty much par for the course.