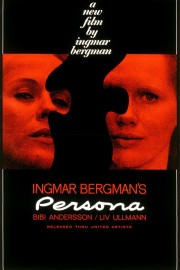

Persona

It became abundantly clear in watching Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona” for the first time in nearly 2 decades that when I first saw it, I was not ready for it, emotionally, spiritually or critically. So much of the film became lost to where I’m curious what, exactly, inspired me to give it an “A” in my personal memory banks. Was it out of a sense of needing to feel like I liked the movie? That I understood it? Because watching it again, I’m fairly certain that I probably didn’t truly like or understand the movie back then. Now, I have a better understanding of the film, and I can very much say that I liked it on it’s own terms rather than a sense of critical responsibility. The same thing could be said with Bergman’s other great masterpiece, “The Seventh Seal,” which also required years of looking at films and becoming acquainted with Bergman before I understood what he presented to me.

The film begins with the light turning on in a projector. We are at the beginning of film history. We also see moments of brutality and violence spliced in before finally seeing Elisabet Volger (Liv Ullmann) on stage during a performance. She has suddenly stopped speaking. Is it stage fright? Is it something more? We never really find out, as we next see her in a hospital being treated. We next meet Alma (Bibi Andersson), a nurse who is being tasked with caring for Elisabet, whom has stopped talking. She does laugh when Alma has a radio on, and she hears something funny, but that is all the verbal communication Alma is able to get out of her, and even that could simply be a hallucination of Alma’s the way that Bergman frames it. The head doctor decides that the hospital might not be the best place for Elisabet’s treatment, and she offers Alma the chance to go out to her summer cottage by the sea, hoping that the atmosphere will help her. At first, it seems to work, but Elisabet still will not talk, leaving Alma to fill the silence with stories of her own life. When she is tasked with delivering a letter to the doctor from Elisabet, though, and finds herself reading the unsealed contents, she feels betrayed, and the strain causes her to take unorthodox steps to get the actress to open up.

What I’ve seen of Bergman’s films from the ’60s fascinated me. I’ve only seen one of his “Silence of God” trilogy (“Through a Glass Darkly”) that started the decade, but three of his other films from later in the decade (“Persona,” “Hour of the Wolf” and “The Passion of Anna”) have shown remarkable insight into a more adventurous level of storytelling through cinema than you would ever guess just experiencing the likes of “Seventh Seal,” “Wild Strawberries” or “Cries and Whispers.” My favorite of those three remains the Gothic horror tale “Hour of the Wolf,” but the psychological thriller at the heart of “Persona” is definitely not far behind. The film starts off as a drama of healing but turns into a battle of wills as Alma is pushed to greater extremes by Elisabet to try and get through to her. In the letter Alma finds, we see Elisabet not as emotionally damaged but fully conscious of what she is doing, and that sends Alma down a morally, and professionally, dubious road that includes “accidentally” leaving a glass shard out for her to step on, and getting so upset that she threatens Elisabet with a pot of boiling water. That elicits a verbal response from Elisabet, but the verbal communication is short-lived. Gradually, Alma is the person becoming emotionally unhinged, and starts to see herself becoming as manipulated and distant as Elisabet is, which Bergman shows in some of the most haunting shots in any movie he ever made. This is a sparring match between two actresses that Ullmann and Anderson perform brilliantly, even though one is practically silent throughout the entire film and the other is talking constantly. Once we, like Alma, catch on to Elisabet’s true nature, it is a battle for Alma’s soul as she begins to behave in ways unfitting a nurse. Bergman’s film is a chess match between these two characters, and while there appear to be moments of friendship and bonding early on in their trip to the cottage, it soon gives way to anxiety about Alma’s sense of self, which Bergman and his longtime cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, capture hauntingly. On the surface, “Persona” is a simple story, but as we dig deeper into the psychology of these two women, we see that there is a depth of pain that has led Elisabet to this moment, as well as a sense of ecstasy that Alma has repressed in her seemingly happy life.

There are two monologues that Alma has that get to the bold psychological soul of Bergman’s riveting film. The second one comes near the end, with Alma near the end of her rope with Elisabet, terrified about the prospect of “becoming” like her, as she recounts the story of Elisabet’s child, almost as if she is channeling it from Elisabet’s psyche. Bergman plays it back-to-back, the first time focusing on Elisabet’s face, the second time on Alma’s. This leads to the unforgettable shot where Bergman merges the two women’s faces into one, which is possible by the actress’s similar facial look, and a masterstroke that gooses the tension at just the right moment. The first one, though, is even more extraordinary, less for it’s thematic importance, but for how genuinely erotic and haunting it is when said by Alma. Early in their time at the cottage, Alma shares a story of her and a girlfriend who went sunbathing by the ocean one day while Alma’s husband went into town. They are found by two young men, and the girlfriend, unashamed by their peeping, gets them over to the girls for some fun. It is vividly told by Alma, and tells us a great deal about her personality- her persona, if you will. It’s one of the most honest and powerful moments in the film, and one of the most arousing passages in movie history, so detailed that you almost feel as though you are watching it. This is the type of adventurous, literate storytelling that drives many of Bergman’s greatest films, and it’s something that makes it impossible for me to think that I wasn’t quite sure how I felt about the movie for many years. It helps that I’m older, wiser, and able to understand someone who deals in symbolism the way Bergman does at this point in my life.