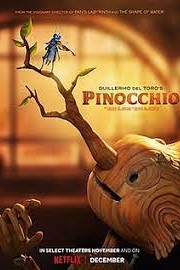

Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinnochio

I shouldn’t be that surprised that Guillermo Del Toro has taken Carlo Collodi’s beloved tale, and transplanted it to Mussolini’s Italy. There is something about children tested during the time of fascism that has always fascinated Del Toro, whose “The Devil’s Backbone” and “Pan’s Labyrinth” took place at the time of Franco’s rule in Spain. That will probably put a lot of people off of the film Del Toro and co-director Mark Gustafson have made, but what it also does is place it firmly within a fantasy world we recognize from the director of “The Shape of Water” and “Crimson Peak”; this is “Pinnochio” as told by the Brothers Grimm, and it is a haunting, beautiful film.

The film begins by having Sebastian J. Cricket (Ewan McGregor) tell us the story of Geppetto (David Bradley) and his son, Carlo. Geppetto is a woodworker who is making a crucifix for the town church when tragedy takes Carlo from him during WWI. He goes into a deep depression, unable to work or feel anything but grief, until one day, he decides he is going to make himself a new son. He chops down the tree by Carlo’s grave, and- in a drunken rage- creates the puppet who will become Pinnochio (Gregory Mann, who also voices Carlo). In the night, the blue fairy comes to Pinnochio and imbues him with life, and gives Sabastian a task- make sure he becomes a good boy, and you will have one wish. From there, the story of Geppetto and Pinnochio begins.

You will find some familiar elements at work in Del Toro’s vision, but ultimately, this is not the same Pinnochio you remember from Disney. The ways in which the film plays with the fantasy elements of the narrative within the framework of its new setting is fascinating- for Del Toro, Pinnochio is a living being, capable of death, but how that plays within the construct of the story is not so much for dramatic effect, but thematic. What we see when Pinnochio “dies” is a continuation of the bargain the fairy makes with Sabastian, and sets stakes every time Pinnochio comes back; it also gives Del Toro, Gustafson and their brilliant animators a chance to create a dark world that is another layer of threatening to Pinnochio.

Stop-motion animation is the most tactile form of animation, and in this film, it is used to create genuinely potent imagery, and a world that feels real and authentic. The use of colors in the background, the movements of the characters, the details in their sculpting, it’s all rich and beautiful to behold, and fits perfectly for the darkness of Del Toro’s vision.

Having the film set in the world of fascist Italy makes the human choices Pinnochio as to work through as part of his growth that much more urgent, and the ways in which he rebels that much more satisfying. I may be making it sound like a downer- and to some, it will be- but this is a film for kids in the same way “The Dark Crystal,” “Labyrinth” and something like “Spirited Away” is; the characters walk in a world of darkness, but they are afforded moments to share joy, and no, the songs are not as catchy as those in the Disney classic animated film, but they are filled with delight because of the performances, and Alexandre Desplat’s score is deeply affecting throughout.

The film ends in a familiar way for people who know the story, but also in a way that makes me think Del Toro LOVES Steven Spielberg’s “A.I. Artificial Intelligence.” That film famously uses the story of Pinnochio as a way of moving David towards a goal, and a purpose. The ending, at the time, was polarizing, in part because of what people projected on what Stanley Kubrick might have done vs. what Spielberg did, but also because, when considered, it is bleak. Del Toro and Gustafson go for a similar note here, and the resulting impact floored me in the same way Spielberg did in his film. In the end, “Pinnochio” is not necessarily a film I’ll revisit regularly from Del Toro, but it is one I’ll always remember fondly for the risks it takes, and the way it left me when the credits began to roll.