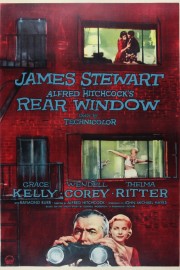

Rear Window

Alfred Hitchcock spent his entire career experimenting with, and perfecting, the storytelling structure of the thriller. He had a legitimate “prestige” film with his first American production, “Rebecca,” but even that more than qualifies to be considered in the same genre vein as “Vertigo,” “Psycho,” “North By Northwest” or “Strangers on a Train.” This particular attention to genre is likely why Hitchcock did not receive an Oscar until the Honorary one he got at the end of his life, but that snub has always been attributed more to the stuffiness of the Academy than any lack of worthiness on Hitch’s part.

If you want to know exactly what made Hitchcock the greatest of all-time, one only needs to watch his 1954 thriller, “Rear Window.” The film lands firmly in the middle of the astounding run of creativity that possessed Hitch between 1951 (“Strangers on a Train”) and 1963 (“The Birds”), although I would extend that to include 1964’s “Marnie,” as well. Even more than “Psycho,” “North By Northwest” and “Vertigo,” this is about as definitive an expression of Hitchcock as an artist as you can get. It’s equal turns romantic, funny, emotional and suspenseful, and it’s one of the most inspired pieces of cinematic storytelling in the great filmmaker’s career.

Point of view is important to the overall impact of “Rear Window.” Even before we see Jimmy Stewart’s Jeffries begin to watch the people in the apartments around his neighborhood, Hitchcock’s camera establishes the framings and movements we will see throughout the remainder of the film, moving between one window and area of the courtyard to another in ways that resemble the human eye looking at things. Later, we see the use of irises during such scenes to symbolize the use of binoculars and a long range camera lens, which Jeff, as he’s called by his friends, uses to help himself see better, especially after a wife disappears across the way, and all the signs point to murder. For a film about voyeurism, Hitchcock wants us to be fully complicit in Jeff’s morally questionable behavior, and feel just as helpless when he best intentions backfire on him and those he cares about, especially Grace Kelly’s Lisa. Robert Burks shot several films for Hitchcock, including “Vertigo,” which is the pinnacle of their use of color, but this is their best collaboration in terms of framing and moving the camera. Most of the time, we are watching what Jeffries, a photojournalist whose broken leg is keeping him holed up in his apartment, is seeing in the apartment complex, and it’s a cinematic device that is truly inspired. We are very much in the same quandary that Jeffries is in during the movie, because Hitchcock’s camera doesn’t leave the apartment. It’s a clever play on the “closed room” mystery structure, and ramps up the tension brilliantly in the film’s third act, when Lisa goes snooping in Raymond Burr’s apartment for clues that Burr’s Thorwald did, in fact, kill his wife, as Jeffries suspects.

The screenplay by John Michael Hayes (who also wrote “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” “To Catch a Thief” and “The Trouble With Harry” for Hitchcock) is based on a short story, but it’s all Hitchcock, and is a perfect match for it’s stars, Stewart and Kelly. As Jeffries, Stewart brings his everyman quality to a character whose life is boring because he can’t live it holed up with a broken leg. He’s a man who needs to be in the middle of the action (he broke his leg by getting too close to a race track), but his wheelchair is preventing that. And so, ever the shutterbug, he aims his eye to the people in the apartment complex along the way, telling himself stories of their lives based on what he observes. It’s kind of amazing to me that all of these people would leave their windows and doors open for anyone to see, without giving themselves any privacy, but such is the nature of cinematic spin to tell this story; it’s not really a reflection of life (not always, at least), but a plot device. Among the most inspired touches Hitch brings to the film is to give us, and Jeffries, just enough visual information to make us think Thorwald did, in fact, kill his wife, while also giving us verbal information (provided by Doyle, Jeffries’s detective friend) to make us doubt it and try to see reason. Once the idea is planted in Jeffries’s mind, though (put there by both a woman’s scream, and Thorwald’s behavior after said scream), it’s there for good, and no one will be able to convince him otherwise. There are two fundamental tensions in this train of thought for Jeffries, along with the moral ambiguity of how he came to this conclusion– what if he’s wrong, and he’s framing an innocent man, as the trail for the world to see would imply, or worse…what if he’s right? Either way, the method in which he came to his conclusions is a bit unsettling, as Lisa and Stella (his nurse, played by Thelma Ritter) try to tell him, and wouldn’t necessarily hold up in court. Also, if the truth ever did come out, how would the others whose lives he’s intruded on think? Since his instincts proved correct, we can imagine the answer to question by the last moments of the movie.

An actor friend of mine called “Rear Window” “the perfect thriller,” in his opinion, and it’s hard to argue that. It’s handily the most entertaining of Hitchcock’s great films in both it’s story, and the way it tells that story. It has a genuinely romantic love story between Jeffries and Lisa, and while I didn’t really touch on Kelly’s performance before, let me just say that she has the physique to make us believe she is an uptown fashion model, but the head and heart to make us believe that while she seems like she’d be out of place following the love of her life (Jeffries) around the globe, her love is pure enough to make us think that she’d be perfectly fine doing so. And it’s a gripping piece of suspense from Hitchcock, who meticulously planned out everything in his films, and rarely did a more effective job than he did here. This is a true blue masterpiece of cinema, and more proof that no one did suspense like Hitch.