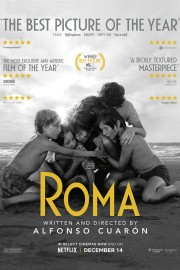

Roma

I let the credits run through to the end of Alfonso Cauron’s “Roma,” not necessarily because I was reading them, but because it felt respectful for the experience that Cauron had just given me. Cauron is a storyteller who respects his characters, their stories, and their truths. Whether it’s the blossoming of young feelings in “Y Tu Mama Tambien” or the complicated nature of friendship and family in “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban,” his modern take on Charles Dickens in “Great Expectations,” the dystopian struggles in “Children of Men,” or the survival in space in “Gravity,” the Mexican master is a personal filmmaker who adapts his vision to the story he’s telling. While he moved me deeper with other films, “Roma” finds him in peak form as a director with a story to tell, and a singular way of telling it.

Cauron, working as his own cinematographer for the first time in his features, has chosen to shoot this film in black-and-white. When a filmmaker does that, it’s because they want to evoke a particular feel in the viewer, whether you’re discussing Spielberg in “Schindler’s List,” Soderbergh in “Kafka,” Burton in “Ed Wood” or Rodriguez in “Sin City.” In Cauron’s case, his reason is to evoke the sense of memories being remembered as we follow the life of Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio), a live-in housekeeper to a middle-class family in Mexico City in 1970. We first meet her as she is cleaning the driveway of the family’s home she is working for. The home is run by Sofia, whose husband is a doctor; they have not just her mother living there, but four children, and Adela, another maid. The film follows Cleo on her daily life and responsibilities in the house, and also sees her and Adela going out with their boyfriends. There is political turmoil in the streets, but, when the doctor leaves for a trip, claiming to go to Quebec, the family is turned upside down, almost as much as Cleo’s realization that her boyfriend has gotten her pregnant.

The politics of Mexico City of the time is something we become aware of throughout the film’s running time, but it’s more a backdrop for making the film feel more authentic than an integral part of the story. The story is about Cleo’s life, but, when marital strife hits the household she’s working at, it’s also about the struggles of women to keep their lives together when men shirk their responsibility. The main part of this story is Cleo’s, as the father of her child she’s carrying- her boyfriend- abandons her almost immediately upon hearing her bring it up, and when she actually confronts him about it later, he threatens her, but Sofia (Marina de Tavira) also becomes an important part of the story beyond just being Cleo’s employer. She takes Cleo to the doctor to confirm that she is pregnant, and confides in Cleo about the truth of what is happening with her marriage so that she can best aid in taking car of the kids. That employer-employee relationship is always present, but we see Sofia and her mother embracing Cleo as part of the family, as well, leading to a family outing near the end where that bond becomes more solidified.

Cauron’s approach here is to make a pretty standard dramatic work- we’ve seen many of these elements and scenes played out many times before- but the love and attention he brings to the film as writer, director, cinematographer and co-editor is what elevates it to one of his best works to date. The respect and love he has for Cleo and the rest of the characters leads to moments of painful, and profound, emotion, whether it’s her trying to navigate the changing situation in her job, or dealing with her pregnancy almost on her own as she tries to talk to her boyfriend, Fermin, about it. The pregnancy is the biggest part of her story, and is responsible for the two most emotionally devastating moments in the film. Aparicio is a wonder in the role, making a phenomenal debut that is tender and sweet to watch for the most part, but when her and Cauron go for the big moments, feels completely honest to life, and can’t help but yank at our heartstrings until they get the waterworks going. Being able to accomplish that without feeling maudlin and overwrought is not always easy, and the result is at least two of the year’s best moments on film.

It was really difficult to separate myself from the hype built up online over how good “Roma” was as I was watching it, but the truth is, this is a wonderful work of cinema. It’s from a great director who found a way to use some of his most technically-challenging ideas on cinema at the service of a simple story without making us feel like those techniques were overshadowing the story he had to tell. As I’m writing about it, I can’t help but liken “Roma” to great works by Tarkovsky, Kurosawa, Bergman and Fellini, all of whom put their personal styles at the service of big themes, even in the simplest of settings. This film brought up strong emotions for me, as Cauron told a story that meant a great deal to him, and made me care about it, as well. Few works of fiction have done it better this year.