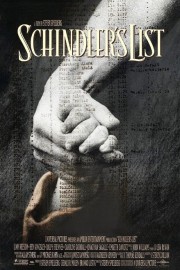

Schindler’s List

**This review assumes that the story specifics of “Schindler’s List” are known to the viewer. Therefore, expect many spoilers. If you haven’t seen the film yet, and would like to go in fresh, then feel free to come back to this review after having seen the film.**

After watching the horrific visions of misguided death and hate in “No End in Sight” and “The Devil Came on Horseback,” I was inspired to revisit Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List.” That’s an odd thing to say about a film that looks at unquestionably the most devastating act of genocide in recorded history (certainly the past century). But Spielberg’s most courageous decision in making a film about the Holocaust was to focus on not necessarily the six million lives lost during WWII, but on some of the 1100 lives saved by a man who had every reason to become another witness to the Nazi’s brutality, to do exactly what he came to Poland to do, and instead became a savior of several generations of Jews to come. His success in itself is enough of a way of honoring the memories of those who died. It’s a story no screenwriter would dare make up; thankfully for Steven Zallian (who wrote this film’s Oscar-winning screenplay with perceptive intelligence and depth), he already had a novel by Thomas Keneally, who learned of the story from survivor Leopold Page while buying a briefcase in the early ’80s, to work from. As Spielberg went into production, other survivors would help fill in the background further (and would appear in the film’s conclusion, with their onscreen counterparts, to lay stones on Schindler’s grave in Jerusalem).

I’ve long felt Spielberg has never received enough credit for the way he develops the Jewish characters in the film, the lone exception to that being Schindler’s accountant Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley in an unforgettable performance as Schindler’s conscience and as a man who must fear death at every moment). Yes, the film focuses in on Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson, who lets us in on Schindler’s cunning and manipulative nature without revealing everything about him), a member of the Nazi party and war profiteer who opens up a factory to make pots and pans, hires Stern to run it, and to find Jews to bankroll it, and hires Jews to work it because they are cheaper to pay than Poles, which means he’ll be all the richer, even if he has to bribe a few officers and politicians (such as Ralph Fiennes’ sinister yet charismatic Commandant Amon Goeth, the third central character in the story) along the way; that was the main thrust of Keneally’s book, and it is the central storyline of the film.

But throughout the film, Spielberg draws us into the everyday lives and fears of some of the Jews that worked in the factory, lived in Krakow, and survived its’ immolation, and would find themselves in Goeth’s labor camp in Plaszow, and later at Schindler’s factory in Czechoslovakia as the war in Europe wound down. They may not share the depth and screen presence of Schindler, Stern, and Goeth, but as Spielberg follows the story, we continue to recognize these characters, and more importantly, we care. That makes “Schindler’s List” a true ensemble film, where every performance is important to the overall success of the film, even though it was generally only the performances by Neeson, Kingsley, and Fiennes that critics pointed to (not without reason, though; Neeson and Fiennes were deserving Oscar nominees, and Kingsley should have been one).

But consider this: Would the film be just as powerful and unforgettable if we weren’t drawn into the struggles for survival of survivors like Poldek Pfefferberg (who would later be known as Leopold Page, who told Keneally of Schindler), who did, in fact, pretend to have been ordered to clear the baggage from the streets during the Krakow liquidation so as to avoid death? Or Chaja Dresner and her small daughter Danka, who risked death by leaving her hiding place in the Krakow ghetto to be with her mother? Or what about the Rosner’s, who go from riches to rags in the move to the ghetto? Or the rabbi who works first for Schindler, then, while in Goeth’s employ, is only saved from death by the luck of Goeth’s weapons locking up? Or what about the scene with the one-armed factory worker, who thanks Schindler for employing him, only to be shot in cold blood later when the workforce is stopped while going to work to shovel snow? And let us not forget Helen Hirsch, the young Jewish woman whose lack of experience as a maid warms her to Goeth (actually, her hands were just cold, tucked away in her coat when Goeth asked the women to raise their hands if any had maid experience), who finds himself falling in love with her (even as he feels no remorse for beating her or casually killing any of her fellow Jews), so much that only an unlucky hand of 21 with Schindler late in the film can pry her away. If Kingsley’s performance was unjustly forgotten by the Academy, Embeth Davidtz’s as Hirsch was forgotten by everyone, despite being the most vivid and memorable in the supporting cast outside of the main three. When we find her in line for the trains to take Schindler’s Jews to his factory in Czechoslovakia, we feel relief and a release of suspense that she will not become one of the Holocaust’s victims.

She almost does, however, as do many on Schindler’s List, when one of the trains headed towards Czechoslovakia is routed to Auschwitz instead. In one of the film’s most vivid scenes in terms of tension, Spielberg shows the Nazi’s most dangerous weapon against the Jews- fear of impending death- at its’ cruelist. The women are loaded off the train, have their hair removed, are ordered to remove their clothes before heading into a shower room. We know from history and the film the possibilities- either the faucets pour water, prolonging life for at least a little longer, or they spray gas, exterminating it. The heartbreaking music by John Williams (one of the best scores he’s ever written, accentuated by violin solos by Itzhak Perlman) is frighteningly suspenseful, commenting on the action onscreen without any reassurance of coming out alive on the other side, while Janusz Kaminski’s haunting black-and-white cinematography uses shadows and light to extraordinary effect. The women’s survival is due to not just a fortunate bit of luck but also the audacity of Schindler, whose very veracity snatches them from the grips of death without showing his real intent, which could get him killed as well.

So many sequences in the film are just as powerful and memorable (the Krakow immolation, the exhuming and burning of corpses by Goeth, and the sifting through luggage and belongings of Jews headed to the death camps in particular stand out in their unblinking sadness), and some for reasons that are unexpected. It’s strange to realize just how much genuine wit is in this film, given how mournful the overlying subject is. For a director whose typically never been one to subtly integrate humor in his films (at least in my opinion), it makes Spielberg’s overall achievement in “Schindler’s List” all the more impressive that it’s brilliantly handled here. Take, for instance, our introduction to Schindler in the night club at the beginning, when a gesture of sending a round of drinks to a couple of SS commanders turns into a free-for-all party that is reminiscent of the scene where young Charles Kane has lured away the staff of a rival newspaper in “Citizen Kane.” Not only is the sequence deviously entertaining, it also sets up the characteristics of Oskar Schindler we’ll witness throughout the film- the womanizer, the gladhander, the showman; the only thing that changes in Schindler throughout the film’s 197 minutes is his motivation for maintaining the factory (and this time in viewing it I consciously attempted to figure out the exact moment in the story where that motivation changed for Schindler, but like every other time I’ve seen the film, I came up with about 5-6 possibilities, another tribute to Spielberg’s storytelling mastery in the film). Other moments of sly wit include a scene in a church between Jewish men who specialize in black market goods and why shoe polish was put in glass containers instead of metal ones, the rescue of Stern from a train headed to the death camps when he forgets his papers, and the arrival to- and eventual departure from- Poland of Oskar’s estranged wife (Caroline Goodall, in a thankless role). It’s a very dry wit I’ll grant you, but it offers some relief from the horror within the rest of the film without being insensitive to it.

If Hollywood storytelling makes its’ way into “Schindler’s List” at all, it’s in one of the final scenes, when Schindler- now a fugitive with the war over- and his wife leave the factory in Czechoslovakia in the dark of night. He is presented with a signed letter from his workers explaining everything, as well as a gold ring (the gold taken from the fillings of one of the workers) with the inscription, “Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire.” Schindler then breaks down, crying about how he could have saved a few more people with his car and his other rings. Supposedly, the breakdown of emotion never happened, but that doesn’t lessen its’ impact. I think it’s a way for Spielberg to speak for the audience watching, and for those who did nothing to stop the loss of life, and lived to regret it. It’s his way of saying that we could have done more, that we CAN do more in the face of such evil, and to get us to act, no matter how difficult it may seem (that he’s done so in his own life with his founding of the Shoah Foundation, which records and archives for educational purposes survivor testimonies, further raises the bar for the rest of us). I liken it to a similar moment at the end of “Saving Private Ryan,” when a dying soldier says to Ryan, “Earn this”- perhaps Spielberg’s way of speaking for all of the veterans of the Greatest Generation to all of us who came after, asking us to earn the freedom they fought so bravely to maintain. Lofty sentiments to be sure, but oh so important to consider in times when we let genocide in places like Darfur and Rwanda go unchecked by the international community and when we find ourselves embroiled in moral and military conflicts of our own making, such as the disaster in Iraq.

I feel as though my evolution as a moviegoer and critic can be attributed, in many ways, to my experiences watching “Schindler’s List.” When I first saw it in theatres in 1994 with a group from our church, I admired it to be sure, but the saw film less for its’ artistic accomplishments and historical importance than for its’ awards cache, its’ vindication of Spielberg with the critical community (and Oscar in particular). Three years later, I would watch it again (not my first time since then) on its’ Network TV premiere, and the film’s artistry washed over me, leading to my complete emotional immersion in the film, and a deeper sense of what the film was saying as a genuine work of art. That I’ve continued to revisit the film every so often isn’t to say I find myself entertained by the film, but inspired by its’ meaning as both art and, essentially, a morality tale about a man who acts in ways that will hopefully, in future years, inspire others to act when they would normally just sit back and think that no one person can make a difference.