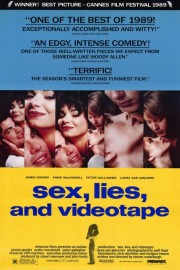

sex, lies, and videotape

Steven Soderbergh’s “sex, lies, and videotape” was the start of a revolution. It was an indie sensation that put Robert Redford’s Sundance Film Festival on the map as a place for the discovery of independent cinema and new voices in film. (The film also went on to win Best Picture and Best Actor for James Spader at the Cannes Film Festival.) It became a box-office hit for distributor Miramax, who would go on to be the leading indie distributor of risky and popular independent films.

But most importantly, it was the first film from writer-director Soderbergh, who would go to have one of the most adventurous and exemplary careers in modern film. Over the next 20-plus years, Soderbergh would move effortlessly and brilliantly between more commercial efforts like “Out of Sight” and the “Ocean’s” films and experimental projects like his second film (“Kafka”) and “Schizopolis.” Not really one to make the same film twice (except for the popular “Ocean’s” franchise), he never really has made another film like his debut, though.

The film starts in broad strokes in introducing the characters. First we see Andie MacDowell’s Ann in a therapist’s office; she’s telling the therapist about fears she’s had recently about where we’ll put all the garbage we throw out. We see her husband John (Peter Gallagher) at his lawyer job. We see Graham (Spader), who looks like a drifter, as he’s driving into town. And we see Cynthia (Laura San Giacomo), Ann’s sister, who we will discover is having an affair with John. Graham is a friend of John’s from their days in college, and he is coming back in town and living with John and Ann for a few days before he gets his own place. But Graham and his peculiarities will challenge all three as the story movies between well, sex, lies, and videotapes.

Soderbergh’s approach is analytical as both a writer and director. His work is more like a therapist than a director- observing his characters; listening to their conversations; non-judgmental in what his characters do. That last part is key to the film’s success. All of the characters in this film are flawed and compromised in their own ways: Graham uses his camera to hide behind, pretending to be close to the people he films but never really accomplishing true emotional intimacy; John is not only having an affair but also seems to have no real emotional connection with Cynthia, who has no qualms whatsoever about screwing her sister’s husband, let alone opening up intimately in front of Graham’s camera; and while Ann is arguably the most sympathetic character, she not only fails to open up honestly with the people around her but also judges everyone around her because they don’t really meet her expectations for how people “should” behave. Soderbergh is merciless in how he portrays these characters, and how their views evolve over the course of the film; that he has actors capable of playing these varied and sometimes visceral personalities is a sign of the brilliant caster he would be over the years.

That incisive approach to filmmaking has been the key to his success as a filmmaker. Out of that observant tone, however, has grown a fearless and brilliant passion for the medium that has resulted in experimenting in front of (he starred in “Schizopolis”) and behind the camera (from his Oscar-winning “Traffic” on, he would work as his own cinematographer). The films he’s made, be it Hollywood productions like “The Informant!,” “Solaris,” and “Erin Brockovich” or indie experiments like “Bubble,” “Gray’s Anatomy,” and “Full Frontal,” are all unique and original creations that take a look a human nature and the reasons we do what we do, and doesn’t back away from what Soderbergh (or his audience might find). And watching “sex, lies, and videotape” again, you can see clearly that he never betrayed the intelligence and risk-taking he showed in this first film.