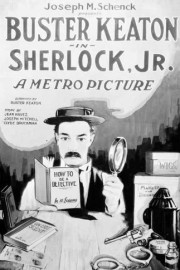

Sherlock Jr.

At first, I think I might have appreciated Buster Keaton’s “Sherlock Jr.” more as a film of iconic status with critics than I did on its’ own terms with me. But through the course of a dozen or so viewings since I first saw it in 1998, it is now a movie I cannot imagine living without seeing. A film that’s one of the best I’ve ever seen (it’s held steady at #7 for years), as well as one of my favorites (#10 now as of 7/16/05). If I could only show a person one silent film ever, it would be this one. It would be hard to do (the silent era is a rich and rewarding exploration), but “Sherlock Jr.’s” that type of movie.

So what is this movie about exactly? In story, it’s about a projectionist, who wants to be a detective, who dreams himself into the movie he’s showing. In theme, it’s about what the movies do to us when we watch them. The great ones, anyway. What’s that exactly? They allow us to live out our dreams, and sometimes- at their most powerful- reflect our realities. They do the former by showing us the lives we want, allowing us the opportunity to go on the journey with our hero through ups and downs before the lights come up, the credits roll, and we go back to our reality, inspired- again, at cinema’s best- by the life we’ve just seen unfold. They do the latter by presenting believable- or not-so-believable- situations populated by believable characters who don’t feel like they were created by a screenwriter, but pulled from real-life itself, giving them personalities we can identify with and delight in following through even the craziest situations. For me, “Sherlock Jr.” does both, and so much more.

If you want to see the full potential of cinematic comedy played out onscreen, watch the films of Buster Keaton, and watch “Sherlock Jr.” in particular. At a time when “daring” comedies are just trying to one-up the next guy in profane and disgusting humor, watching Keaton’s films- made roughly 80 years before- will show you no one has ever been more fearless than Buster. When you hear someone talk about modern comedies doing anything for a laugh, consider this- has anyone recently ever dodged and landslide of boulders, each one getting progressively bigger? Has anyone had a wall of a building fall down around them, with only a strategically placed window keeping it from crushing them? Has anyone stood at the front of a real train, and had to movie railroad ties…as the train was moving? Has anyone ever held onto a log, over the edge of a waterfall, and had a safety wire break, and yet, they continue with the stunt anyway? Buster did all of this, in comedies as versatile as “Seven Chances” (1925), “Steamboat Bill Jr.” (1928), “The General” (1927), and “Our Hospitality” (1923), respectively. Sure, Jackie Chan (a charismatic actor obviously inspired by Keaton) and others have done their own stunts in the recent past, but they were working with every safety net and precaution imaginable- Buster was not. More than that, though, Buster made it look easy- and funny- in an era that such chances must have seemed impossible- and dangerous.

But Keaton’s genius was greater than the sum of his physical risks- no filmmaker has told more likable stories of human perseverance. In every film- at least, the 10-plus I’ve seen as of this writing- Keaton told simple stories about young men with their eyes on achieving a goal, mostly in pursuit of the woman he loves, and is thrown obstacles by either people or nature that want to get in his way. A simple story, told many times, in a variety of ways that provided different predicaments with different solutions, but always has its’ heart in the same place. The story of Keaton’s railroad operator in “The General” (generally regarded as his masterpiece) isn’t the same as the story of Keaton’s determined, athletically-challenged student in “College,” which isn’t the same as the story of his newsreel photographer in “The Cameraman,” which isn’t the same as his city boy down South to collect his inheritance in “Our Hospitality,” and so on. In other words, if you think he told the same story again and again, you’d be wrong. Each one provided different twists, different obstacles, different possibilities for “The Great Stone Face”- as he was known for his always-sullen expression in his films- to create imaginative and hilarious comedy.

Case in point, no other Keaton film was like “Sherlock Jr.”. The story- what you need to read of it, that is- you know from the second paragraph of this essay. The details of the story, you shouldn’t get from a simple summary (isn’t it better to follow the story as the movie tells it?). With Keaton, it was the execution, and the ideas that the story inspired, that distinguished each movie. In “Our Hospitality,” it’s the generations-old feud between his family and the family of a woman he just met. In “The Cameraman.” it’s his constant professional failures and personal embarrassments while trying to make a career from being a newsreel cameraman. In “Sherlock Jr.,” it’s the idea of a dreamer imagining himself into the story that’s unfolding on the silver screen, a dream shared by a great many people- myself included, and probably Keaton as well. It’s an idea that inspired some of Keaton’s most visually-inventive ideas, most especially when dreaming Buster- his characters never had names of their own- leaps onto the screen, and into the action. It’s a rare gag for Keaton that seems to come more out of the possibilities of the medium than out of the story (though it works beautifully as both), but it’s a gag you’re glad he took the chance to make it, because the movie is impossible to think of without it. It’s easy stuff now, with the special effects tools we now have and the possibilities of doing the stunts in front of rear-projection. But the excitement of Keaton’s sequence- which he is more integrated in than what would be allowable from rear projection I suspect- comes from the idea that in 1924, it’s something that audiences would have been amazed by, though even I still watch in amazement despite being privy to many of the tricks of the trade through DVD commentaries and documentaries. The effect Keaton achieves through such imagination is liberating and hilarious, especially when the film is faster than he is. If it seems as though I’m giving away a great surprise in revealing the centerpiece of “Sherlock,” it’s only because a) others before me have as well, and b) I know there’s so much I’m not giving away. This sequence is indeed “Sherlock’s” comic highpoint, but it’s far from its’ only one- this 45 minute masterpiece (yes, it’s barely longer than an hour-long episode of TV) has much in store for the viewer who discovers it.

I love “Sherlock Jr.” for a great many reasons, as I hope I’ve made clear. The comedy is one reason to be sure, but it’s not the only one. I love it for it’s ideas of what comedy should be- it’s not mean-spirited or low-brow like so many are now- and the comic ideas it comes up with. I love it for it’s story, at times full of adventure and clever excitement, at other times playing it sweet and quietly- and sometimes comically- moving (the last scene is one of the great boy-gets-girl cappers in the movies, at once acknowledging the ways movies inspire us but also the ways movie logic doesn’t always add up in the real world). And I love it because it embodies- precisely- why we go to the movies, and why we identify with them; like Newsweek’s David Ansen said in a 1998 article about the movie’s first century, “But the movies are our contemporaries- our buddies, our crushes, our lovers,” though I would add to that that they are also our dreams as well. Few films have felt so friendly to me.

But most importantly, I love “Sherlock Jr.” because I- like Buster’s character- am a dreamer (and a projectionist). I’m a hopeless romantic who has let the movies take over my thoughts on how the world should be, and how I want it to be. I have my own dreams and ambitions beyond what I do now, and I love the character’s courage in the way he goes about in achieving them. But in the end, he realizes it is only a dream, his wanting to be a detective. But you know what? He’s content with who he is in reality as well. And in the end, some of that dream does come true for him with the newfound confidence he has in himself. That is the ultimate reward of watching Buster Keaton’s films- like the movie for his projectionist in “Sherlock Jr.,” they allow your dreams to become a reality…if only for a short time. And when they’re over, maybe you feel a little better about your reality, and have the courage to do what might have been difficult before. That he has become one of my all-time favorites should come as no surprise.