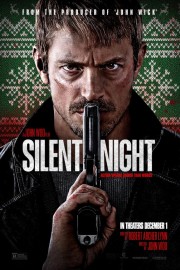

Silent Night

Some of the things John Woo is known for are gone from “Silent Night”- the balletic action scenes with their slow-motion; the doves signifying peace in a violent world; even his heroes with dual guns are seen sparingly. Joel Kinnaman’s Brian isn’t a cool heroic character, but someone who lets violence change him forever. That’s a relatively new character in Woo’s films, and Woo isn’t afraid to lean into it. In a way, Brian is similar to Sean Archer in “Face/Off”- both lose themselves to vengeance, but Archer leaves himself enough of a foothold that he can come back to the light. Even before his family is broken beyond repair, we can see in Brian’s eyes that there’s no coming back for him.

One of the key elements of most of Woo’s best films is essential to “Silent Night” working as well as it does- the melodramatic tone of his narratives. Much has been made about how “Silent Night” is “dialogue-free”; that’s not exactly true- Woo uses texting and radio broadcasts to give us some context and important interactions, but for 95% of the movie, it’s imperative for Woo and the actors to find a way to express important ideas and information through actions and looks more than words. For the most part, the film succeeds, and I think that’s because Woo understands the power of images to convey emotions. The way he uses close-ups of eyes, especially between Kinnaman and Catalina Sandino Moreno as his wife, Saya, as their marriage deteriorates when their son, Tyler, is killed in a drive-by shooting where he was an innocent bystander, is the most impactful example. Brian tries to exact revenge on the gang members whose violence took his child from him in the moment, but it leaves him near death, unable to speak. By not giving any of the characters much in the way of dialogue, he forces them to meet Brian where he is, and you get used to it fairly quick. The only time it feels forced is when Kid Cudi’s detective comes into the picture, but the way Woo uses the character, there really isn’t much for him to say; he’s simply someone looking on, unsure what to make of Brian until he forces Vassell- Cudi’s character- to pay attention.

“Silent Night” is not top tier John Woo, nor do I think it really could have been, given the gimmick it utilizes. Woo’s melodrama thrives when his characters are able to express themselves with both words and action. Even though Chow Yun-Fat’s characters do their best work with their guns, imagine films like “The Killer” and “Hard-Boiled” without scenes of brotherhood with other characters. “Silent Night” is Woo pushing himself in a similar way some of the great masters do when they remove one, particular part of their cinematic toolbox for a story. When he’s locked in on the action, even without the flourishes of his iconic style, his action scenes in this film have a brutality and energy to them that is hard to shake. For most people, the cinematic precedent Woo is chasing would be “Death Wish,” but if you’re familiar with James Wan’s “Death Sentence” with Kevin Bacon, that is closest to this film’s tone; both are about characters whom are transformed by loss, and on a path of nihilistic self-destruction where there’s only one way for their stories to end. We follow that path for Brian every step of the way.

There’s so much I love about this film. I love how Brian is just a regular man whose life is made bleak by violent loss; his vengeance is going to be methodical and well-prepared, but even when he takes action, you can see how the odds of him surviving are not great. Kinnaman and Sandino Moreno are fantastic in the early parts of this film, which hit me in the gut. The cinematography by Sharone Meir and editing by Zach Staenberg are important parts in the way Woo is able to tell this story without dialogue, and that he succeeds as much as he does is a credit to these collaborators. Marco Beltrami’s score plays up the melodrama, as well as the darkness, reminding me of what a wonderful musical chameleon he can be, and goes well with the songs Woo uses throughout, including a music box Brian uses to remind himself of why he’s doing this. There are nods to Woo’s previous films, but everything makes sense when it comes to the internal logic of the film. But what I love most about this film is that, even if Woo doesn’t reach the heights of “The Killer,” “Hard-Boiled,” “Face/Off” or “Red Cliff,” he’s willing to push himself to tell a story outside his wheelhouse, and in doing so, shows us there’s a lot of juice left in one of the most influential film careers of the modern era.