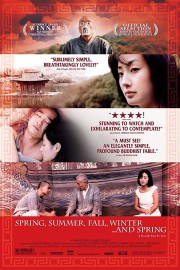

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…and Spring

Spring: On a floating monestary in the middle of a lake, the aged Monk teaches the young apprentice in the solitary ways of Buddhism. When the apprentice plays a childhood game by tying rocks to the bodies of a fish, a frog, and a snake, the Monk teaches the young boy a lesson in tying a stone to his back, which he will not remove until the boy unties the rocks from the bodies of the fish, frog, and snake. The young boy is told that if any of the animals are dead, that he will carry stones in his heart for the rest of his life. Two of the animals have died.

Summer: Now a young adult, the apprentice must face his first contact with the outside world young woman arrives at the monestary for healing. Feelings of lust overcome the apprentice as he sleeps with the daughter, who’s now healed. When the master discovers the two, he tells the young woman to leave, and tells the apprentice that his feelings can lead to posession, which will only lead to murder. A slave to his passions, the apprentice leaves the monestary to be with the woman.

Fall: After being away in the modern world for many years, the apprentice returns to his old Master as a fugitive. He has murdered his love in a crime of passion, and has returned to seek refuge. But the police arrive to arrest him. But his master knows what his apprentice needs before he is locked away- inner peace, which he achieves by carving out symbols his master has drawn for him on the platform the monestary presides on with the knife he used to commit the murders. Only then does his master, who later dies, allow his apprentice to be taken away.

Winter: After many years have passed, the apprentice returns to the monestary- long since empty and trapped in the ice of the lake- as he endures to cold to make his life and home the monestary he continues to find himself returning to. A young woman- who keeps her face hidden- and her infant child come out to the monestary. After the woman dies after falling through the ice, the apprentice takes one final journey, up to the peak of a near-by mountain, shirtless, with only a weighted rock ties to his body and a statue in his hands.

…and Spring: The apprentice’s life comes full circle, as he is now the master to the young child the woman brought to the monestary.

That I’ve outlined the entire story for you- something I try not to do usually- is no accident; it’s simply the only way I can really summarize “Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…and Spring” for you. Of course, the risk is that you simply won’t see it, and just take my review as your only experience. Don’t. Meditative and poetic, this Korean film is one of the year’s truly wonderful pieces of cinema, a movie that doesn’t follow conventional storytelling devices, tells its’ story more with images than words, and lets the emotional truth of each scene speak for itself. In that, “Spring” reminds me of the cinema of Russia’s Andrei Tarkovsky, an auteur whose films (which include “Andrei Rublev” and “Stalker”)- as regular readers will know- I cherish. However, instead of the sometimes punishing elogated running times of Tarkovsky’s work (even die-hards have to admit his final film, “The Sacrifice,” is a difficult sit-through at a not-so-brisk 140 minutes), writer-director Kim Ki-duk- who also plays the apprentice in the final sequences- keeps his film at a respectable 100 minutes. That’s not to say Ki-duk skimps on story compared to Tarkovsky; in fact, “Spring” is- in a way- richer in story than some of Tarkovsky’s epics, which were many times drawn out by using lovingly-composed and methodical tracking shots. Kim ki-duk creates a film that’s contemplative without being ponderous, which isn’t as contradictary a statement as you may think. Like Tarkovsky, he observes the actions happening onscreen without taking part in them, or asking you to do so. All he asks is that you consider what is happening, and discover the meaning of each action for yourself. Everything in the movie happens for a reason, even if it isn’t clear at the time it happens. The point is where you end up, not how you got there, although to dismiss the journey is a mistake in itself. For me, that philosophy is the film’s beating heart. Is it a philosophy I share in my own life? To an extent, though I think the journey is every bit as important as the place you end up at.

I was inspired by both here. I have little doubt you will be too.