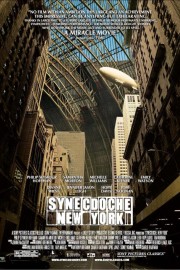

Synecdoche, New York

With each progressive film, screenwriter Charlie Kaufman has shown an uncanny sense of displaying the sexual angst within creative individuals. The puppeteer in “Being John Malkovich” (played by John Cusack) is full of sexual frustration with regards to a particular coworker (Catherine Keener), who ends up romantically linked with his wife (Cameron Diaz) while she’s inhabiting the body of John Malkovich. In “Adaptation.,” the screenwriter (Nicholas Cage) develops a crush on the author of the book he’s adapting (Meryl Streep), who has actually developed a romantic fixation on her subject (Chris Cooper). In “Confessions of a Dangerous Mind,” his game show host subject (Sam Rockwell) finds himself torn between the sweet girl he’s seeing in his regular life (Drew Barrymore) and the mysterious woman (Julia Roberts) he finds himself with as a CIA assassin. In “Human Nature,” the hormones of a nature author with all over her body (Patricia Arquette) are thrown into overdrive when an eccentric animal man (Rhys Ifans) and a crazier scientist (Tim Robbins) enter her life. And in “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” the romantic longing between Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet cannot be undone by even the most scientific procedures of memory loss, but the lust of people around them (namely Elijah Wood as a creepy book store guy and Kirsten Dunst as a worker for the doctor (Tom Wilkinson) who created the procedure) comes from a most shallow place.

In his first film as a director, Kaufman once again finds sex and creativity hopelessly intertwined into a surreal comedy-drama of life, or at least something like it. Philip Seymour Hoffman is pure acting excellence as Caden Cotard, a stage director in New York whose adaptation of “Death of a Salesman” with a younger cast gets him noticed, but in the words of his wife’s friend (Jennifer Jason Leigh), there’s nothing personal of him in it. Not long after the show closes, and his painter wife takes his daughter to an exhibition of her work in Germany (never to return), he gets what he calls a “genius grant,” which he feels he must earn by creating an unmistakably original work.

There’s a little problem with Caden, though. He’s acutely aware of his own mortality. With each scene change early on, it appears he’s hung up on another physical affliction, and sent to another specialist. Whether he finds out the exact problems that ail him is not the point- the point is that he will die. And with his wife gone in Germany with their daughter, a cute-but-slightly off box-office attendant (Samantha Morton) who admires him, but eventually finds herself wanting a real relationship (even if she and her husband live in a perpetually-burning home- don’t ask), and a failed affair that leads to marriage and a child with one of his actors (Michelle Williams, who with this performance and her Oscar-nominated work in “Brokeback Mountain,” has erased any real memory of her stint on “Dawson’s Creek”), Caden will appear to be forced to live out his life alone. And his therapist (a biting a wittily self-centered Hope Davis) is no help- even she’s sick of his whining. How did he get here? Such a complex question becomes the focus of his work, and a project that will encompass the rest of his life.

At this time, it is only fair to tell you- I somehow managed to fall asleep during this movie. Not out of boredom- my regular readers will know that has more to do with my health than with any sense of disappointment I had with the film. So how can I go about reviewing it? Well, with “Synecdoche, New York,” it’s not that hard, since several of the surprises Kaufman and Hoffman (both of whom deserve Oscar nominations- if not wins- for their work here) have in store are unimaginable to give away anyway. Let’s just put it this way- if you’ve seen any other movie with a Kaufman screenplay, what exactly do they have in common? My point exactly. More than any other behind-the-camera artist in modern film, Kaufman is a master of misdirection and philosophical meditations on life-and-death-and-art. He’s a kindred spirit to the likes of Bergman, Tarkovsky, and Kubrick in their explorations of human nature, spirituality, and the maddening ordeal of creativity. Did any of them make the same movie over and over? Again, my point exactly.

The tone of Kaufman’s film is tragic, but through its’ slyly-droll wit and the sheer exuberance of his actors, few films feel so alive (which made my tendency to sleep all the more disappointing in this case- when my eyes were awake, I couldn’t take them off of the screen). Compared to Kaufman’s other screenwriting efforts, at first glance it’s my third favorite after “Adaptation.” and “Eternal Sunshine.” Like his other films- and those of the two directors who’ve brought most of his scripts to life (“Adaptation.’s” Spike Jonze and “Eternal Sunshine’s” Michel Gondry)- it will find a home in my collection, and in repeat viewings- one of which will be as soon as f-ing possible so I can see the whole thing- it will find itself in the company of “Adaptation.,” “Andrei Rublev,” “Ikiru,” “Big Fish,” “The Whole Wide World,” “Saraband,” and other films that have tried to get down to the core of the human experience, in all its’ joy and pain, and dare to explore what makes it worth living.

To all those who might question my motivation to review a film partially seen so ecstatically, I ask you this- would anyone whose feelings weren’t genuine write so much about the film? My point exactly.