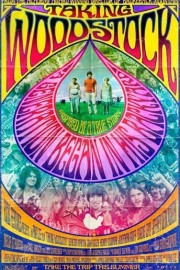

Taking Woodstock

Immediately, and probably inevitably, the first thing one notices in Ang Lee’s nostalgic comedy is the music. Surprisingly, though, it’s not any of the music that played during the iconic 1969 concert but the lovely and endearing score by Danny Elfman.

It’s a fitting change-of-pace from the rebellious sets by Joplin, Hendrix, The Who, and others who came to define a generation with their sound. But Lee isn’t telling the story of what happened that weekend (which just had its’ 40th anniversary)- the landmark 1970 documentary took care of that.

Instead, Lee and his long-time producer/writer James Schamus frames the story of that concert of “peace, love and music” as a coming-of-age story about Elliot (Demitri Martin), a young man trying to save his family’s motel when fate hits in the summer of ’69. A nearby town has recently denied a permit for the Woodstock festival. Elliot- who was going to put on his own music festival- decides to invite them out, and with the help of local farmer Max Yasgeur (Eugene Levy), well, the rest is history.

Elliot hits some speedbumps along the way- namely with the locals and their exaggerated (and, as would prove true, not-so-exaggerated) sense of what will happen if hippies overrun their town, but we all know the litergy of iconic moments that turned the show into a phenomenon. Lee doesn’t miss a beat, though. His film isn’t as heavy or profound as earlier triumphs like “The Ice Storm,” “Brokeback Mountain,” and “Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon,” but it’s an entertaining comedy that brings back fond memories of those moments in our lives that give us an opportunity to be a part of something extraordinary.

Lee- as always- is a master caster of roles both big and small (most especially Emile Hirsch as Elliot’s ‘Nam-scarred friend, Levy at his square best, Martin in an endearing and sincere star turn, Liev Schreiber as a cross-dressing head of security, and Imelda Staunton and Henry Goodman as Elliot’s parents), while his cinematographer Eric Gautier captures brilliantly that hazy feel and innovative split-screen that the Oscar-winning documentary used so effortlessly to put the audience in the middle of the action.

True, Lee’s vision of the event is idealized, but that’s how we look back at Woodstock now anyway- as a perfect moment, without limits, within a larger storm of change and unrest. Lee puts us in the middle of it brilliantly.