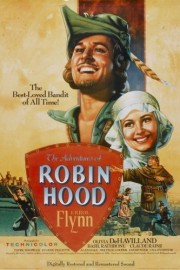

The Adventures of Robin Hood

“The Adventures of Robin Hood” so easily charms with the classic tale that it soars high above just about any other version we’ve ever seen, whether it’s the Disney version, Kevin Costner’s “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves,” and especially the unfun, uninspired Ridley Scott reimagining with Russell Crowe that tried to justify the need of a prequel. Directed by Michael Curtiz (“Casablanca”) and William Keighley, this 1939 version has the thrilling adventure of a swashbuckler and the glorious sheen of the early three-strip Technicolor process that made those early color films unforgettable experiences at the time, and memorable to revisit now.

The color cinematography, by Tony Gaudio and Sol Polito, isn’t the only memorable behind-the-scenes aspect of “Adventures of Robin Hood” that resonates to this day. If you know anything about me, you know, of course, that I’m referring to the score by Erich Wolfgang Korngold, which has been celebrated as one of the finest in movie history, although I haven’t really acknowledged it as such over the years, mainly because I’ve only seen the film once up to now. Watching the movie again, I understand why it’s garnered the reputation it has among film soundtrack fans. The son of a music critic, and a prodigy who caught the eye of no less than Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler, Korngold moved from opera and classical music to film scores after fleeing Europe in the ’30s after Hitler’s rise to power, and his music has the energy of an operatic score that fits right in with the legendary story of Robin Hood, and distinguishes it from the traditional sound of film music that had become established in the ’30s by composers like Max Steiner. He only wrote 20 scores in his 12 years of working in the business before he left to rejoin the classical world, although he was unable to re-establish himself as a “serious composer” before his death in 1957. No matter– the full-blooded drive of his scores for films like this, “Captain Blood” and “The Sea Hawk” had assured him a legacy as one of the most influential film composers of all-time.

It’s not just the cinematography and the music that assures “Adventures of Robin Hood” of it’s reputation as a great movie entertainment. At the center of it all is the lead performance by Errol Flynn as Robin Hood. Flynn was a great adventure star in the ’30s and ’40s before alcoholism consumed him, and turned him into a parody of himself, and it’s easy to see why– his Robin Hood is an easy charmer, full of playful exuberance and noble purpose as he does his part to keep the kingdom of King Richard, who has been kidnapped on his way back from the Crusades, from falling into ruin when Richard’s brother, Prince John (Claude Rains), and his aide, Sir Guy of Gisbourne (Basil Rathbone), take control of the throne in his absence. He establishes himself in Sherwood Forest as an outlaw for the people, taking from the Prince and Sir Guy as he sees fit, which, needless to say, doesn’t sit well. All of the familiar story points are hit: the archery match that is set up as a trap; the bridge fight with Little John (Alan Hale); the first meeting with Friar Tuck (Eugene Pallette), and the courtly romance with Maid Marian (Olivia de Havilland), which is beautifully scored by Korngold, and the driving thrust of many of the films most memorable scenes. This is an old-school adventure film in every sense of the word, though, and it has the great fight scenes to back that up; Flynn did a lot of his own stunts in the swordfights, including the classic finale against Rathbone, and even though effects and action scenes have gotten bigger over the years, few are better. The choreography, the lighting (which leads to shadows on the walls of the castle that add much to the sequence), and the music that adds to the thrills of the scene are all iconic parts that make up a great whole. The same could be said for all of the parts of this great movie, as well, from the performances (including de Havilland and Rains) to the direction to the focused, enjoyable screenplay to the costumes and art direction that shimmer in front of the color cinematography mentioned earlier. No, it’s not a “realistic” film in any way, shape or form, but the world it creates feels real as we watch it, and ultimately, that’s what matters most.