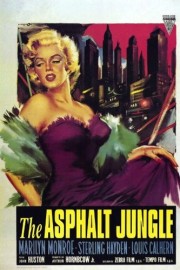

The Asphalt Jungle

The films of John Huston’s that are best loved are hard-edged crime dramas, or feature hard-nosed protagonists, but that covers up the fact that, in fact, the director was probably one of the filmmakers most interested in translating the written word to on-screen action. Not a one of the films I’ve reviewed for Sonic Cinema has been based on an original screenplay- each one is a literary adaptation, although the similarities between the source material and final film aren’t always clear. The greatness of Huston as a director stems from his ability to turn something that was vivid and evocative on the page and turn it into a film that comes alive with vibrant images and an emotional charge. Not every film was great, but none of them were boring.

His 1950 drama, “The Asphalt Jungle,” is a film noir in the tradition of his 1941 debut, “The Maltese Falcon,” but focused on the criminal element rather than a weathered hero like Phillip Marlowe. Based on the novel by W.R. Burnett, “Jungle” follows a series of events that brings three main criminals together (each with different backgrounds and skill sets) for a jewelry heist that could set them up for life, but like any other time when disparate people team up for a single goal (such as in Huston’s “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre”), greed and distrust turn partners into enemies, and what should be a simple plan into a situation that spirals out of control. If the film lacks the emotional grounding that made “Madre” so powerful, it’s only because none of the characters in “Asphalt Jungle” are tragic heroes in the same way the characters in “Madre” are, but rather hardened criminals who don’t have noble intentions rather than just making enough money to retire, although that was the same goal the prospectors in “Madre” had, as well. Huston’s genius as a storyteller, though, is how we manage to sympathize with them anyway, even if their motives serve no one else but themselves.

‘Doc’ Erwin Riedenschneider (Sam Jaffe) is a criminal mastermind who has just been released from prison. He’s anxious to get back in the game, and has an idea for a million-dollar heist. He needs help, though, and enlists a variety of criminals- professional safecracker Louis Ciavelli (Anthony Caruso), hunchbacked getaway driver Gus Minissi (James Whitmore), ‘hoodlum’ or hooligan thug Dix Handley (Sterling Hayden) and white-collar, untrustworthy lawyer Alonzo Emmerich (Louis Calhern), who is the crew’s financier- to pull of a robbery at a jewelry store. Lookout men, difficulty opening the safe, close calls with the cops and troubles unloading the goods are just a few of the situations the crew finds itself dealing with after they make their getaway.

If there’s a character that I found myself being sympathetic towards as the film unfolded, it’s Dix Handley. A low-level thug, Dix finds himself behind with his bookies when we start the film. He has frequent gambling debt, and can never seem to get lucky. For him and his girl, Doll Conovan (Jean Hagen), Doc’s proposition could be just what they need to get ahead for the first time. Doll is your typical mobster moll, but her and Dix have a connection that is affectionate and loving, even if they fit their archetypal roles perfectly. Hagen and Hayden have wonderful chemistry and give us a great emotional arc to follow. The fallout of the heist becomes secondary to seeing them get away, especially after Dix is shot during what should have been the exchange with the fence for the diamonds. The last part of the film is, largely, devoted to their getaway and it’s a credit to not only the actors but Huston that we want things to work out for them, although the gun wound to Dix makes us realize that it probably won’t happen. Huston could certainly make entertaining films, but some of his best films involved tough men in vulnerable situations that both tested their mettle, and showed it. Dix shows his, and it makes his demise a tragic one, even though we’ve seen him to terrible things.

John Huston is a director who, while being acclaimed by critics and historians, has never really struck me as a director who has gotten the respect he deserves on the whole. His filmmaking style is not as easily noticeable as Hitchcock or Welles, but he is a great narrative storyteller who uses visuals when they can enhance the story he is telling. He’s one of the filmmakers who helped invent the film noir genre, and thus, the visual style that came to define it. Film noir isn’t just about the images, though, but the type of story and characters it follows. With “Asphalt Jungle,” though, Huston is setting the template for another tried and true sub-genre, and that’s the heist film. “Out of Sight,” “Ocean’s Eleven” and even Michael Mann’s “Heat” all owe a debt to what Huston accomplishes here. It doesn’t hit the same level of greatness as “The Maltese Falcon,” “Treasure of the Sierra Madre” or “The African Queen” did, but it was a smart evolution for a filmmaker who didn’t always swing for the fences creatively like some of his peers, but nonetheless moved the art of filmmaking forward by bringing a literary sensibility it was sometimes missing.