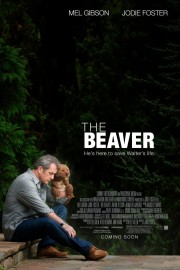

The Beaver

The last time Mel Gibson left me speechless after a movie, he went on to win an Oscar for directing “Braveheart,” and that film’s score planted the first seeds in me to want to compose film music. The years have not been kind to Mel, or should I say, Mel has not been kind to Mel. The jovial and charming star has turned into a troubled and controversial cautionary tale; his ultra-religious belief system, put out front with his 2004 film, “The Passion of the Christ” (which he directed, but did not star in), and the sickness of alcoholism (and probable mental illness) has led to a very public meltdown the likes of which we hadn’t seen in celebrity culture in quite some time. (Even considering Charlie Sheen’s equally disturbing meltdown earlier this year, I think Mad Mel’s was worse.) It’s been a painful sight to see for someone who has always admired Gibson’s talents as an actor and filmmaker, and respected the values he seemed to stand for as a husband and father.

That same pain shoots through every frame of Jodie Foster’s new film, her first as a director since 1995’s “Home for the Holidays,” in which Gibson stars as Walter Black, a family man who is suffering from depression. All he does is lay around at home all day and go to run his father’s toy-making company, which is suffering under his lack of leadership. One day his wife, Meredith (Foster), kicks him out, an act met with confusion by their younger son, Henry (the poignant Riley Thomas Stewart), and gratitude by their eldest son, Porter (Anton Yelchin). It is a sobering image to see Gibson’s Walter, slouching in a suit that seems ill-fitting, to walk out of a liquor store with a box filled with alcohol. When he doesn’t have room for the booze in his car, he throws some work papers and other things in the dumpster. This is where he finds the beaver puppet that will allow him to be him again… or will it?

Dealing with emotional issues such as the ones highlighted in “The Beaver” is tricky– dealing with them in the way director Foster and writer Kyle Killen do in this film borders on the miraculous. Yes, the idea of a man who is speaking through a beaver hand puppet 24/7 is pretty silly (and the notion of him being taken seriously at work is a leap), but as someone who has suffered more than a few bouts of depression, which sometimes bordered on the suicidal, I know from firsthand experience what Walter is going through, and I appreciate the risks he takes during the movie to try to connect with the outside world. Part of what makes Gibson’s performance so remarkable is how much we wonder whether Walter’s outward appearance (i.e. his improved relationship with his wife and youngest son and his ability to lead at work) is truly leading to a happier and healthier mental outlook. We get the answer in two fearless scenes: One at a restaurant on Walter and Meredith’s anniversary and the other when Walter has lost himself in his emotions, leading to a violent confrontation that is all the more powerful considering what we’ve learned about Gibson through his troubling legal scrapes. This film (and this performance) is autobiography through and through for Gibson, and it is as emotionally devastating as anything I’ve seen on-screen in a while. Matching him every step of the way is Foster, who gives her bravest performance in years as a wife who is uneasy about keeping Walter around with the Beaver on his arm but who also enjoys seeing this side of her husband. Much has been written about the sex scenes Foster has with Gibson and the Beaver, and indeed the glimpses we see are absurdly funny, but Foster– who has supported Gibson throughout his real-life breakdown –is more concerned with the emotional issues at the sad heart of this story, and she has the confidence as a director to not back away from them and to follow them through to some pretty dark places.

There is more to “The Beaver” than Walter’s story, however. A parallel plot concerns Porter’s own identity crisis: He has become worried about all the similarities he seems to share with his father– he’s also made a fair amount of money at school writing papers for fellow students, and he has a gift for doing so in their own voice. His class’s valedictorian (Jennifer Lawrence) has asked him to write her speech for graduation, and while they strike up the beginnings of a friendship (and possibly more), he sees that she has her own troublesome issues. Yelchin and Lawrence deliver strong and emotional work as these two young people whose lives are turned upside down by family tragedies; it’s a compliment to both of them that their storyline would have made an equally fine film in its own right.

“The Beaver” is one of two films Mel Gibson has had in the can for a while, ready for release. (His other, the Mexican prison drama, “How I Spent My Summer Vacation,” is currently awaiting a distribution pick-up.) How long it will take audiences to forgive Gibson his transgressions and be ready to watch him again is impossible to say, but the disappointing box-office numbers for “The Beaver” imply it will be a while. That is a shame, although not entirely unexpected. Gibson’s performance is going to be difficult to beat when Oscar time comes around; however, beyond a possible Golden Globe nomination, I don’t see Academy voters being ready to forgive him just yet. I was uncertain about my own feelings on Gibson like everyone else, when the darkness and illness he has tried so hard to keep out of the public eye lunged out with a vengeance, first during 2006’s DUI arrest that ended his marriage of 25 years, then last year in the legal battle with his ex-girlfriend (who is the mother of his eighth child) in which we got an unsettling glimpse into Gibson’s dark side. But while I find Gibson’s actions in real-life despicable, he still remains a gifted actor, and I hope he is able to resume his fascinating directorial career sooner rather than later. “The Beaver” solidified that much in my thoughts on Gibson, and it did so much more when I take a more personal look at the film, and the director and the star who made it.