The BFG

One of the most disheartening moviegoing experiences I’ve ever had was little to do with the quality of the film, but what the experience in watching it in theatres said about modern day audiences. In 2002, my mother and I went to a showing of the 20th anniversary release of Steven Spielberg’s “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial,” which had been rereleased in a “Special Edition” much in the same way the “Star Wars” trilogy had been five years earlier. Some of the choices Spielberg made in doing that release are, arguably, more egregious than many of the ones Lucas made in his trilogy, but that wasn’t the disheartening part. For someone who grew up in the ’80s, “E.T.” was one of the strongest pillars in my childhood alongside “Star Wars,” a film that was endlessly rewatchable (my mother says we watched it 12 times in theatres when it was released) and helped define what we looked for in films. In that theatre in 2002, though, it felt as though the magic that Spielberg conjured for me as a kid was lost on the relatively sparse crowd, which was used to savvy, star-filled animated films and cutting-edge technology. What had happened to audiences where a simple story of a boy and an alien forming an unforgettable bond couldn’t grab them like it did me?

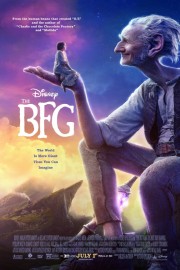

Based on the book by Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and James and the Giant Peach author Roald Dahl, “The BFG” was automatically on my must-see list because of Spielberg, but what really grabbed me was that the screenplay would be written by Melissa Mathison, who passed away last year, and had also written “E.T.” for Spielberg (as well as “Kundun” for Martin Scorsese in 1997). The book was published in 1982, the year of “E.T.,” so that is another bit of fun trivia for how these films are connected, but there’s definitely a narrative commonality than is shared between the films. Both are seen from the point-of-view of their young protagonist, in this case, Sophie (Ruby Barnhill), an orphan in 1980s England who is up late at night when she sees something outside of her window. It turns out to be a giant, but not just any giant- a Big Friendly Giant (performed by Mark Rylance, who just won an Oscar for Spielberg’s “Bridge of Spies”), or BFG, as Sophie calls him. He picks her up out of her bed, and takes her to Giant Country, far away from the mainland, and his home. He catches dreams, mixes them together, and puts them into the hearts of people in the human world. His friendly, non-human-eating ways are not shared by all giants, however, and when some of them get a whiff of a “human bean,” as they call humans, it could spell trouble for not just Sophie, but BFG.

The years have changed Spielberg as a director, as post “Schindler’s List” and “Saving Private Ryan,” adult storytelling concerns have seemed to be the spark of his excitement as a filmmaker over the more escapist entertainment that turned him into a household name in the ’70s and ’80s. Gradually, however, he has started to return to that more escapist vein, whether it’s “Adventures of Tintin” or “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull,” and he’s started to find his sea legs again with such films. (I can’t wait for his next one, “Ready Player One.”) Even before he turned to more serious fare, though, purely family entertainment was in short supply, with only “E.T.” and “Hook” seeming to fit that bill. While at its best, “The BFG” is every bit as wonderful as “E.T.,” it hues more towards the flawed realm of “Hook” in the second half of the film by barrelling straight through a narrative choice of Dahl’s in his original story that took me out of the fantasy world Spielberg had so effortlessly taken me to by bringing some seemingly unnecessary “real world” solutions to a fantastical tale of giants and dreams. Having never read Dahl’s book myself, I had to research to see whether the choice really was a part of his original story or an invention for the screen- that it was, in fact, a part of Dahl’s story makes me more understanding of Spielberg’s handling of that particular material, but also makes me wish he and Mathison had realized how wrong it was, and figured out a more imaginative solution to the dramatic tension between BFG and Sophie against the human-eating giants of the tale. Thankfully, that “real world” solution is quickly enacted in the film, and ends with Sophie in a much more hopeful place than she was at the beginning. If it had been as drawn out as the scenes in Buckingham Palace are that really lost me, I don’t know that “BFG” would even be getting the grade it is from me.

At this point in his career, it feels unlikely to really get a poorly-directed and produced film from Spielberg, and as “Tintin” showed, he is embracing new technology as well as any filmmaker who has been working as long as he has. It’s easy to point to the work by production designer Rick Carter, ILM, cinematographer Janusz Kaminski or John Williams as examples of how Spielberg still understands how to create a reality on-screen better than anybody, but the use of performance capture to bring The BFG and the other giants to life, and to allow them to convincingly share scenes with Sophie, is a marvel to behold. As played by Rylance in his second-straight great performance for Spielberg, The BFG is imposing and threatening even when he shows himself to be kinder and more human than his giant counterparts. We believe the scenes BFG and Sophie (who is well-played by Barnhill), and we believe the bond between the two that transcends the technology that was required to bring one of them to life. The film’s most wondrous movement shows BFG taking Sophie to the magical tree where he catches dreams at, and starting from the moments he dives into a pool of water and comes out the other side (literally), it’s a beautiful piece of fantasy filmmaking that rivals anything in any film you can imagine. (I was reminded of some of the otherworldly images of “Life of Pi,” myself.) It is Spielberg and his fellow artists at their finest at taking us to the heart of a story, and it’s a moment that I will never forget, even if it is followed later by moments I wish I could. In that moment, the magic of “E.T.” was rekindled in me, and in the filmmaker who brought us that unforgettable story the same year Dahl gave us the one he is telling now.