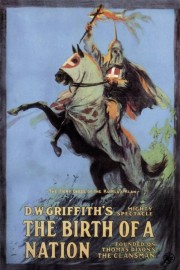

The Birth of a Nation

Ok, admittedly when I chose “Birth of a Nation” as my next film in this series last week, I didn’t take into consideration the fact that I’d be reviewing arguably the most controversial film ever made in regards to race relations in the United States during Black History Month. In retrospect, however, it seemed like an ideal opportunity to really look at the film through fresh eyes again, and see what the years have done to my perspective on this film, historically seen as the first significant feature-length film in the American cinema.

As Roger Ebert has long been fond of saying, “It’s not what a film’s about, but how it’s about it.” Taking that into consideration watching D.W. Griffith’s film, however, is a tricky business. For his first foray into feature-length filmmaking, Griffith chose to adapt the Thomas Dixon’s play “The Clansman,” about Southern Seccession from the Union, the Civil War, and the Reconstruction after the North was victorious. Immediately, you get a glimpse of where Griffith’s sensibilities lie just by the title. But Griffith sees a bigger story possible in the framework of the play. “Nation” uses this story to tell parallel stories of a Northern family (the Stonemans, the patriarch of whom is a leading congressman before the war) and a Southern family (the Camerons), both of whom lose a great deal in the war. At times, the two families intersect, with friendships built before the war, and tested during the war.

For the first half of the film’s nearly three-hour running time, Griffith tells an absorbing personal drama within a large canvas, as he shows us glimpses of the fighting (which can stand up to the likes of “Braveheart” and “Saving Private Ryan” in their scope and intensity), historical moments like the surrender of the South, and Lincoln signing important proclamations into law, as well as his assassination by John Wilkes Booth (played by Raoul Walsh, who would later go on to direct “White Heat” with Cagney and other classic films). But watching the film again, Griffith’s focus remains on the two families even after the war ends and Reconstruction begins. Most poignant is the story of Stoneman’s daughter Elsie (Lillian Gish)- who is shown at the theatre when Lincoln is assassinated- although all of the stories regarding the Stonemans and Cameron’s are compelling, even when Cameron son Ben is shown as one of the founders of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction.

It’s during the Reconstruction era- the second half of “Birth of a Nation”- when the film hits its most controversial points on race. For the first half of the film, blacks have been largely unseen in the story, except for glimpses of servants (including some in obvious blackface makeup) and a raid by a Northern black company against the Cameron household, although Griffith does point out in his title cards that the company is led by a corrupt white officer.

During Reconstruction, we see the North’s attempts to bring racial equality to the South, and how it falls on deaf ears, although for some from the North, the opportunity is seen more for a chance to finish what Sherman started in his march through the South. Stoneman is in South Carolina with Elsie to oversee the process, with his mulatto servant Lynch- who has romantic eyes for Elsie- helping bring rights to Southern blacks. But Stoneman’s trust in Lynch is misplaced, with Lynch looking instead to lead a black revolt more than find a peaceful existence between the races.

It’s not just in the character of Lynch where Griffith- using Dixon’s story as the jumping off point- shows offensive racial stereotypes and behavior. We see black soldiers shoving white voters away from the polls on an election day that’ll sweep many blacks into state office. A black-controlled state legislature passing amendments like interracial marriage (which in actuality was illegal even into the 1960s) and how whites on the streets would be forced to salute black soldiers. We also see title cards for black interactions with stilted English used to show the illiteracy of Southern blacks at the time.

We also see the formation of the Klan, with Ben Cameron inspired by seeing a playing game where white children hide underneath a white sheet, and jumping out at black children, scaring them off. By this point, Elsie and Ben are engaged to by married, but Cameron’s involvement in the Klan breaks things off by Elsie. No doubt there’s some historical merit to what Griffith depicts in this part of the film, but that doesn’t make the scenes of blacks being portrayed as lustful predators for white women and scavengers looking to terrorize whites with the same disregard for their rights they had for so long any less offensive to watch, especially when the Klan is shown as a heroic force by driving away a group of blacks who’ve surrounded a white family in their house.

Make no mistake, as cinema, the film- even at its morally-lowest- is enthralling drama, with Griffith setting the artistic standard for all that came afterwards in his use of storytelling techniques he’d been developing in his short films prior to “Nation.” But in presenting Dixon’s racially (and politically) one-sided story as an equivalent of historical truth, Griffith is also guilty of an irresponsibility that forever scars whatever artistic accomplishments he achieved in this film. A year later, Griffith looked to atone for this film with “Intolerance” (and later, provided a sympathetic and moving look at interracial love in “Broken Blossoms”), but while these later films stand superior to “Nation” on both artistic and moral ground (“Intolerance” itself still rates as one of the greatest film epics of all-time), Griffith could never completely make up for the damage “Birth of a Nation” caused. The film was seen as an affront to African-Americans (rightfully so), and is still so inflammatory that when a theatre tried to show it several years ago, the NAACP successfully campaigned against it, and it led to a revival of the KKK in the United States.

Watching it today, the film is easy to admire for its’ artistic craft- which set the standard for all cinema until Orson Welles redefined what cinema was capable of with “Citizen Kane”- even while condemning its’ politics. It’s the sometimes-thorny middle ground that critics and audiences are posed with when presented with a film (or filmmaker) that doesn’t meet their moral standards. It’s the issue that’s plagued Roman Polanski since his conviction of statutory rape in the ’70s, and one that is now applied to “Braveheart’s” Mel Gibson after the anti-Semetic controversy over “The Passion of the Christ” and his drunken tirade before the release of “Apocalypto.” In fact, it was the charge of homophobia that stemmed from a scene in “Braveheart” that led me to choose “Birth of a Nation” as the next film is this series. While that controversy has always seemed like a mountain made of a molehill to me, in choosing the story he decided to make his most historically-important film with (a film that took the techniques of the day and displayed them in the best example of their use to date), D.W. Griffith made a mountain impossible to scale, even when the controversy surrounding “The Birth of a Nation” forced him- and us- to reflect on the worst in ourselves.

Author’s Note: Roger Ebert wrote a fascinating review on “Birth of a Nation” for his own Great Movie series, which can be read here.