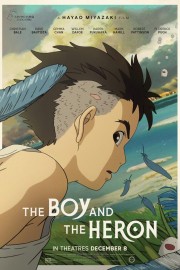

The Boy and the Heron

The more one watches Hayao Miyazaki’s films, you get the impression there’s something personal to him in each and every one. He must have had a vibrant fantasy life that accounts for the way that he blends fantasy and reality into his films. At their core, however, his best films give us a glimpse of lonely people- especially children- whose adventures tend to bring them closer to the life the real world has for them than they expect. Here, we have another child struggling with the realities of what his parents are going through. Unlike in “My Neighbor Tororo,” however, the fantasy world in “The Boy and the Heron” is one that brings danger, not comfort.

Miyazaki’s film begins with unspeakable tragedy. A family is awoken in the middle of the night by a fire. The hospital that Mahito’s mother works at is on fire. He races to get there, but he is unable to save her. Some time later, he moves out to the country, and an old family house with his father and his new wife, whom is pregnant, and- we learn- Mahito’s aunt. The old women who help at the house are struck by just how much the Mahito looks like his mother. It’s a struggle at first; we don’t get the feeling that Mahito is being intentionally hostile to Natsuko- his aunt and stepmother- but there are small acts of rebellion. When a grey heron comes to visit Mahito, and promises his mother is still alive, he’s curious, but when Natsuko finds herself lost, as well, that is when he needs to act.

There are visual elements we’ll be familiar with from his other work. Comically large noses and faces. Cute little creatures. Animals with humanistic personalities. and finally, lush, painterly backgrounds. It feels like, with every new film, Miyazaki’s work gets richer and richer, not just thematically but visually. My introduction to Miyazaki was 1997’s “Princess Mononoke,” and his work was remarkably beautiful even then; I think “The Boy and the Heron” is even more breathtaking than that. His approach to his landscapes feels more impressionist and striking, as if he has entered a new phase of his creativity. Or maybe it’s the sense of time catching up to him. One gets the sense that, as he feels his own mortality coming, he wants to impart every value he can on his audience, and if that means getting more personal in his storytelling, that’s what it means. Here, he has an old man who gives Mahito a chance at a sense of responsibility in a world he’s created, but if he accepts, that means he might lose the sense of growth and connectiveness the real world has to offer. Power is corrupting, however, as is displayed before we see Mahito truly make his choice. I feel like, by making most of his protagonists children, Miyazaki is imbuing them with the faith that a younger generation will make the choices an older generation was too scared to make.

One of the things that has always stood out with Miyazaki’s work is how they don’t really present fantastical threats, except in how they represent man’s hubris destroying the natural world. That is the thrust of “Mononoke,” and true in a handful of other films, but his films are often about fantastic experiences helping the main characters grow into more empathetic individuals. Both are ultimately true in “The Boy and the Heron,” but it’s interesting to see how past and present are used to give them a different perspective on life, as well. This might be the most metaphysical of Miyazaki’s films, and it was as beautiful a use of the concepts as we’ve seen in terms of how it builds the characters, especially Mahito. This is classic Miyazaki- imaginative, adventurous, emotional (in this case, doubly so with a fantastic score by his longtime collaborator Joe Hisaishi) and artistically pristine. I’m glad he’s going to try and continue giving us more movies.