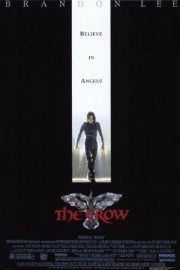

The Crow

Brian’s review of “The Crow”

Originally Written: July 2000 (w/ amendments in August 2006)

Some stories have a particular aura about them that seems to give them the power to touch us deep within our very souls. The story of “The Crow”- as imagined by James O’Barr- is an example of this. The basic premise is so simple and formulaic that even a writer of considerably lesser talent could make it fly. Two 20-something lovers, Eric Draven and Shelly Webster- just days before their wedding- are gunned down by a gang of thugs for no reason other than just to score some cash. One year later, the titular bird brings Draven back to exact revenge on his murderers, and put the wrong things right. Well, there you have it- the story in a nutshell. Oh, and for the record, a lesser talent could NOT necessarily make this story fly (see the most recent film, “The Crow: Wicked Prayer,” for proof).

However, the furious passion in this quite violent story comes from O’Barr himself, who composed the story- first as a series of comic books, released later in “graphic novel” form- as a way to deal with the devastating loss of his own fiancee in the early ’80s to a drunk driver. This added emotion turns O’Barr’s dark, sadistic revenge tale into genuinely haunting and beautiful poetry- a love story as sentimental and tragic as “Romeo & Juliet,” but as action-packed as the latest Jerry Bruckheimer production.

Actor Brandon Lee- the son of Bruce Lee- was among the many fans who felt O’Barr’s passion leap off the pages. So much so that when producers Jeff Most and Edward R. Pressman set out to make a film version of O’Barr’s story, Lee lobbied hard for the part. He lost 20 pounds to capture the look of Draven- as portrayed by O’Barr- and beat out a group of contenders such as River Phoenix and Christian Slater to land the role that he saw as his breakthrough- a chance to finally break away from his father’s shadow (he had been reduced to making action/comedy driven with a kung fu edge for most of his films) and to become an action star in his own right.

Knowing that makes the following even harder to type. Eight days before shooting was to end, they were filming Draven’s death scene- to be shown in flashback- when something went wrong. The prop gun given to actor Michael Massee- who plays gang member Funboy- wasn’t checked by the crew before it was handed over for the scene. Lee’s job was simple- set off a device in the bag he was carrying to make it seem as if he was shot. Sadly, he was. The tip of a dummy bullet from earlier use in the film was lodged in the gun, so when Massee fired, it struck Lee, who died 12 hours later on March 31, 1993, at age 28. Lee was to marry his own girlfriend Eliza Hutton on April 17.

Over the next couple of months, the filmmakers deliberated over the eventual fate of the film. While many would have been satisfied with shelving the project, Lee’s mother- Linda Lee Caldwell- and Hutton wanted to have “The Crow” stand as a memorial to Lee and a legacy to his talent (according to the producers; it’s unclear whether they really did or not). And so, with some rewrites of the script, minimal use of a double and visual effects (Lee’s role was essentially done by the time of his death), “The Crow” was completed, and released May 13, 1994. The footage when the accident occured was destroyed.

Their efforts were not in vein. The final film is a spellbinder- an intelligent comic book tale of dark beauty and affecting melancholy that also registers on an action film level, as well as stays true to its’ source. Unlike many recent comic book adaptations up until that time (and some since), “The Crow” has a genuine interest in specific aspects of the human condition- albeit ones that are soaked in blood, given the story’s intense violence- and a unique curiosity about the story that allows it to achieve emotional heights usually reserved for films such as “Schindler’s List” and “Vertigo” (though it doesn’t quite reach that level). At its’ core, “The Crow”- both in O’Barr’s graphic novel and director Alex Proyas’ film- is about the acceptance of loss and dealing with the grief of that loss. It also poses a fascinating question- if you were given the chance to come back from the grave one year after your death, what would you do, knowing that your family and friends have probably come to accept your passing- even if it still affects them- and have moved on with their lives? It’s a question that- I’m sure- is rarely contemplated, but one that could have several answers, no matter who you talk to. It’s also one that was at the center of 1999’s great “The Sixth Sense,” only instead of a bird, the dead had a child (Haley Joel Osment) whom could answer their call. Both answer this question, but only “The Crow” does so from the spirit’s point-of-view.

As a visual film, “The Crow” is a marvelous spectacle to behold. This aspect of the film- provided through the collaboration of director Proyas, production designer Alex McDowell, and cinematographer Dariusz Wolski (brilliant work by both McDowell and Wolski)- is visionary in the tradition of “Blade Runner” and Tim Burton’s “Batman” films, and one that is perfectly in tune with O’Barr’s striking look for Detroit- his hometown and where the story is set- in the graphic novel. You can’t take your eyes off of what Proyas and co. have created. And the action- when it comes- is just as astounding on the eyes- as Proyas and editors Dov Hoenig and Scott Smith excel at keeping the film moving at a blistering pace so as to keep the viewer on their toes, as well as recreating the visual logic of comic books- which are meant to be read quickly- onscreen. As Roger Ebert said in his review of the film, it was- at the time- “the best version of a comic book universe I’ve seen” (a statement he would later use to describe Proyas’ next film, the great and visionary “Dark City”). This isn’t to say that Proyas falls back on what I call “confetti” editing to keep the pace tight (see of the action in “Armageddon” and the car chase in “The Rock”). Like the greatest action directors, Proyas understands how to create a gripping action scene through the definition of the location of the action and who’s involved (John Woo is particularly masterful in this technique), so the audience isn’t left guessing who’s still alive and who’s dead and isn’t subject to the head-splitting migraines that can be caused by incoherent editing practices. The boardroom sequence near the end of the film is a masterful example of this, as is the gripping conclusion set in a church.

As far as the script is concerned, it’s less brilliant and interesting than the visuals, but pitch-perfect at maintaining the dark atmosphere of the story. Adapted by David J. Schow and John Shirley, the script finds the dark heart of the story, and so strongly defines the relationship between Draven and Shelly (portrayed in the film by Sofia Shinas) to where we completely sympathize with the couple and willing to appreciate the purity of Eric’s mission. The characters in the film aren’t overly complex or three-dimensional, but in the film it doesn’t matter- they’re developed enough (with the main ones played with such distinct personalities) to make the film compelling. Even the villains are given some interesting weight- in particular, the characters of crime lord Top Dollar (a wicked and wickedly witty Michael Wincott) and half-sister Myca (Bai Ling) and their perverse relationship. Once interesting note about the script is that after Lee’s death, it was rewritten by several people in order to bring a more poignant dimension to this intensely-violent story (they also threw out a character from the graphic novel- the Skull Cowboy- that was meant to be a sort of guide for Draven). One of the things they did was to deepen the relationship between two of the supporting characters- Officer Albrecht (Ernie Hudson from the “Ghostbusters” movies), who is at the scene the night of the murder, and Sarah (Rochelle Davis), a teen whom was friends with the couple- as well as their relationships to the people in their lives (Albrecht’s ex-wife and Sarah’s druggie mother (Anna Thomson, from “Unforgiven”)). Both Hudson and Davis bring surprising gravity to their roles, making them instantly memorable (oddly enough, neither are featured too prominently in the original story, though some of their interactions with Eric are similar). Also added was the voiceover by Sarah at the beginning and ending of the film which delineates the mythology of O’Barr’s story for the viewer and serves as a fitting touch of perspective to the story as a whole.

Music is also a huge reason for “The Crow’s” success. The musical musings of the likes of Joy Division and The Cure helped inspire O’Barr while he was creating the comic series back in the ’80s, so it’s only appropriate that music would be integral for the film as well. For the film, Proyas creates a deft blend of alternative rock and orchestral score that is exhilarating to listen to, especially for film music fans. The song soundtrack- for my money the best ever- features Gothic works by the likes of The Cure, Nine Inch Nails, Rollins Band, and Stone Temple Pilots’ hit “Big Empty,” whose sounds are flawlessly blended into a seamless masterpiece of a soundtrack album and whose themes echo those of the film, thus making it a perfect companion album. For me, though, the real musical jewel for this film is the brilliant score by Graeme Revell. It’s a stunning musical work that blends rock guitars, classical strings, World Music solo instruments, and techno percussion into a furiously passionate, genuinely haunting, and completely original musical soundscape unlike anything you’ll hear anywhere else. And when combined with its’ alt rock counterpart and Proyas’ visuals, the result is a fabulous achievement in the combination of film and music.

Overall, though, there are only three people without whom “The Crow” simply wouldn’t work. The first is James O’Barr, because without his story, there would be no film. The second is Alex Proyas, in my opinion the finest director to make the leap from music videos to motion pictures. His intelligence and artful ease in worlds such as this and “Dark City” is evident in every frame and is sure to give directors such as Tim Burton, Paul Verhoeven (“Robocop,” “Total Recall”), and Terry Gilliam (“Brazil,” “12 Monkeys”) a run for their money.

The third of this triumvirate is Lee, who provides “The Crow” with its’ grieving heart onscreen in a striking final performance. Having seen all of Brandon Lee’s previous films (of which there are five), I can truthfully say that “The Crow” is his best film, and it shows in his performance. He was quoted as saying that “as an actor, he wanted to be Mel Gibson,” and from all indications here, that was not an exaggeration. Not only did he have the physical prowess to make it as an action star, but like Gibson, he also had the ability to run a full spectrum of emotions for the duration of a film, from funny to down-to-Earth romantic to fierce-as-Hell savage; in other words, a layered, immensely enjoyable, and incredibly passionate performance that audiences could relate to. For me, it ranks as one of the best performances of 1994, and one of the most memorable of the ’90s.

In fact, that brings me to one of the most interesting aspects of “The Crow” for me (hold on- hard-core geekiness coming up), which is how similar I find it to be to Gibson’s tour de force epic “Braveheart”- released a year later- when you think about particular aspects of both films. I know, comparing these two seems like comparing apples and oranges, but hold on. The most glaring similarities for me are between Lee’s Eric Draven and Gibson’s William Wallace; their mannerisms, their motives for violence, and just about every aspect of the characters as a whole make for a compelling dissection. Next are the stories themselves, which I’ll admit are very different, but there are several themes and “beats” that link the two. (OK, on these first two I’ll concede that both films are very archetypal in both story and character, but as both movies are 1 & 2 on my favorites list, it’s worth thinking about I think.) Finally, there’s the music. Notice how Revell’s haunting love theme acts as sort of a precursor to James Horner’s for “Braveheart” (and is it perhaps not surprising that music from “The Crow” was used for the original trailer for “Braveheart?”). Alright, this probably isn’t as odd as I’m making it seem, and I’m pretty certain Gibson didn’t intend the similarities when he made “Braveheart.” Still, food for thought on that subject.

If the film sounds perfect, even I’ll admit that there are some not-too-major flaws in the film. Namely, some of what happens in the film is too predictable, the story is your typical formula revenge thriller when taken at face value, some of the bad guys are a bit too cartoonish and over-the-top (such as gang member Skank), and to some, the violence will be too off-putting and diminish the power of Draven’s mission. Still, I think it’s as close to perfect as any comic book adaptation has ever come.

The film closes with the dedication “For Brandon and Eliza,” to remind us- if we have forgotten- of the price that came with the completion of the film. And the song that plays over the end credits- “It Can’t Rain All the Time,” written by Revell and Jane Siberry (and performed by Siberry)- is just as moving as that simple dedication, with its’ haunting music and melancholy lyrics about love that transcends life and death. The film itself aims for that type of transcendence in its’ final moments, when Eric and Shelly finally find peace, and Sarah- as The Crow flies away- provides the final words of this chapter in “The Crow” mythology (which includes a TV show, three more films, and several more written stories): “When the people we love are stolen from us, the way to have them live on is to never stop loving them. Buildings burn, people die, but real love is forever.” And because of the deep emotion that Brandon Lee provides as Eric Draven, “The Crow” succeeds brilliantly at achieving that in a coda that in uniquely moving and instantly unforgettable.

An Evening with Actress Rochelle Davis and “The Crow”

“In a Lonely Place”– a look at the film’s soundtracks, and their inspiration on Brian as a composer.

**You can hear me discuss “The Crow” soundtrack on the Untitled Cinema Gals Project here.

Originally Written: September 1999

“One day you are going to lose everything you have. Nothing will prepare you for that day. Not faith…not religion…nothing. When someone you love dies, you will no emptiness…you will know what it is to be completely and utterly alone. You will never forget and never ever forgive. The lonely do not usually speak as completely and intimately as James O’Barr does here in this book- so, if anything, at least take this lesson from ‘The Crow’: Think about what you have to lose.”

This quote is from John Bergin’s Introduction for one of the most popular graphic novels of all-time- James O’Barr’s “The Crow,” and it has haunted me since the first time I read it several years ago. As you read above, O’Barr’s novel- which he wrote to let out his pain and anger over the death of his own fiancee in the early ’80s by a drunk driver- was turned into a modest hit film back in 1994 that was itself haunted by the tragic on-set death of star Brandon Lee.

In the following paragraphs, I will be going into more depth about the music, specifically that of composer Graeme Revell for both films, as well as a little “review,” if you will, of the hit song soundtrack, which I’ll begin with now.

Like many soundtracks, the original song soundtrack for “The Crow” was released before the film, and to about as good of reviews as an alternative rock soundtrack could get. When the film was released, however, the soundtrack soared to the top of the charts, which had a lot to do with Stone Temple Pilots’ hit single “Big Empty” as well. The soundtrack went on to sell over a million copies in the US alone.

I first acquainted myself with the soundtrack in early June of ’94- over a month and a half before finally seeing the film. Right away it was one of my favorites, and not just for the music- which is by itself excellent. The album itself should be a model for how to sequence albums. Executive produced by Jeff Most (who produced the film with Edward R. Pressman), Jolene Cherry, and Tom Carolan, “The Crow” soundtrack flows with coherency in not just its’ shift from artist to artist but also in the tone and theme of each song. From the driving pain of The Cure’s “Burn” which opens the album to the blistering intensity of Nine Inch Nail’s cover of “Dead Souls” to the haunting final track- Jane Siberry’s “It Can’t Rain All the Time” (the best and most memorable song I’ve heard for a film of the past 15-20 years)- the 64-minute “Crow” soundtrack takes the listener on a dark, morbid sonic journey unparalleled in movie song soundtrack history (even by the album’s successor, “The Crow: City of Angels”) and earns my vote as one of the best of all-time.

The score is even better than the song CD that overshadows it. In Spring 1999 my fellow students and I in my audio post-production class had to select one CD we love, and do voiceover about it (sort of a precursor to my fan commentaries I guess). If I had to do that project again, I would have selected this score. The only reason I didn’t is because- and this is rare- the credits listed everything but the studio it was recorded at. Composed by Graeme Revell- who cofounded the industrial rock band SPK before turning to film scoring- the scores to “The Crow” and “The Crow: City of Angels” (for my money) belong in the pantheon of greatest film music. I urge you (if possible) to check out these scores, as well as the original film if you haven’t seen it. With both of these extraordinary scores, Revell- whose usual style is from the Hans Zimmer school of action scoring- created music that was not only intensely visceral but- dare I say it- transcendent. Revell has combined the fast-paced percussion and guitar licks from modern action scores with the poignant vocals and orchestral motifs of dramatic writing to creating a listening experience of unusual emotional power.

His success is evident from the first track of “The Crow” score- entitled “birth of a legend,” which begins with the type of percussion you usually associate with rock music (as well as a solo on the Armenian Duduk- later heard in the “Gladiator” score- signaling the film’s mood of tragic melancholy), only to transform by the end of the piece into the first statement of the film’s haunting love theme between Lee’s Eric Draven and his murdered fiancee Shelly. Like the song soundtrack, the score to “The Crow” flows with an otherworldly grace to its’ close with one of the best recent action cues, entitled “last rites.” “The Crow” score does have many visceral action cues (one of which- “the crow descends”- was used in the original trailer for “Braveheart”), notably “inferno,” “captive child,” and “tracking the prey.” But my favorite tracks are the more poignant and- by design- more morbid ones. These include “rememberance,” “pain and retribution” (you may have heard some of this one if you saw the theatrical trailer to “The Sixth Sense”), “believe in angels,” “on hallowed ground,” and “return to the grave,” which brings the film to a striking and unforgettably moving finale.

The score to “The Crow: City of Angels” is just as good, if not- in some ways- better. Part of this is because while the film itself was poorly shot and ditched some of the more intriguing elements of David S. Goyer’s original screenplay (based on the novelization I’ve read), Revell’s music kept the spirit of the original film alive in his brilliant music. Probably because of the film’s setting of the story to coincide with the Day of the Dead celebration, Revell’s music has a feel to it sometimes that can only be compared with Gregorian chant. Revell’s visceral and extraordinary use of percussion from the original is still there, and maybe even more so. But the vocals, as well as the orchestral passages and ambient keyboard parts, are more spiritual and mystical than the original’s were. For highlights, check out “City of Angels,” “Temple of Pain” (track 6 on the tray track list), “Mirangula: Sign of the Crow,” “Lament for a Lost Son,”” Hush Little Baby…” (which has a vocal howl that resembles John Williams’ theme for Darth Maul in “The Phantom Menace”), and “La Masquera,” which brings all of the elements that makes Revell’s scores unforgettable in a powerful cue for the final battle between good and evil in “The Crow: City of Angels.”

Now you maybe thinking- what’s with the subject name? Well, it’s the name of a piece I just completed this evening (9/15/99) that was inspired (in spirit, and in some ways sound) by Revell’s music. It’s also the name of Bergin’s Introduction which I quoted at the beginning of this essay. I’ve been working on “In a Lonely Place” since late June, and tonight was my 5th or 6th (possibly 7th) session working on it, and the finished product is the fourth “incarnation,” if you will, of the work (a 5th incarnation includes an arrangement I did not long after completing the piece for trombone quartet, which was been performed live in March 2001). For the lowdown on why there are so many “versions” of the piece, visit my Society of Composers website and check out the liner notes for it. I will say that it doesn’t contain Revell’s extraordinary use of percussion (though I did try to pay it homage in version 1), and the main melodic ideas aren’t quite as memorable as the one Revell wrote. And I won’t even try to pretend that it’s “transcendent,” although it is (in my opinion) one of my most personal pieces. It’s certainly one that I don’t regret spending as much time as I did on it. I hope that when you hear it, you’ll agree.

Recently watched The Crow after not seeing it from the release date back in 1994. I recall when I saw it then that the Jane Sieberrys song was intertwined more in the movie. Like to point that out I know I am not imagining it. Can you please explain how I hardly heard it this time when I watched it on Netflix? I am so intrigued that I felt like trying to find the answer to this question. Thank you in advanced if you have any insight.

I recently rewatched it in theatres for its 25th Anniversary. The Siberry song has only ever been at the beginning of the end credits, save for when you hear Draven’s band sing the lyric, “It Can’t Rain All the Time,” when Sarah plays the Hangman’s Joke record after first seeing Eric.